|

| Focus:

Privatization |

JETRO,

1221 Avenue of the Americas, NYC, NY 10020 December

22, 2004 December

22, 2004

|

Japan’s $3+ Trillion Postal Privatization to Have Significant

Impact on Financial Markets

|

The “Big

Bang” liberalization of Japanese financial markets in

1998 was expected to change investment behavior in Japan. The

conservatism of Japanese households, however, led them to believe

it was better to maintain the security offered by unlimited

bank deposit guarantees rather than expose themselves to more

risky investments.

These reforms did, however, bring about heightened competition, introducing

the potential for “prompt corrective actions” within

troubled financial institutions by newly empowered regulators. Major

foreign private equity firms also moved to enter this sector. These

forces helped to introduce significant change and major Japanese

banks achieved profitability last year for the first time in a decade.

Furthermore, in 2002 limits were placed on guarantees for time and

installment savings deposits and in April, 2005 extended to all private

bank interest-bearing deposits.

The Koizumi government is now moving to initiate a ten-year plan

to privatize Japanese

postal services -- including it’s $3.3 trillion

Postal Savings System (PSS). This institution, the PSS, holds more

assets than any other in the

world, and has traditionally provided indirect funding for national

development projects. While this helped Japan to establish itself

as the world’s second largest economy, it is increasingly recognized

as a major barrier in Japan’s quest to develop a more market-oriented

financial system. The redistribution of these funds through market-oriented

mechanisms is likely to have a significant impact on equity and debt

markets around the world..

The Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO) provides the following

information, which examines these issues, as well as specific opportunities

and developments that may be of interest to the corporate and portfolio

investor.

|

Late

1990s “Big Bang” Forecast to Change Investment Behavior

in Japan

|

|

Financial reforms

were a central tenet of the “Action

Plan for Economic and Structural Reform”

adopted by the Japanese Government in the fall of 1996. As a result,a

dramatic "Big Bang" liberalization of Japanese financial

markets was enacted on April 1, 1998. This included a revised foreign-exchange

law. Regulations concerning brokerage commissions were also relaxed.

To promote financial sector consolidation, steps were also taken to

ease the regulatory barriers that kept insurance, banking, and other

firms from competing with each other. Foreign financial institutions

seeking a larger share of the $9+ trillion in estimated assets held

by Japanese investors had long been seeking to enter Japan’s

investment trust market. Roughly equivalent to U.S. style mutual funds,

the sale of these instruments had formerly been restricted to Japanese

financial institutions. In December 1997, however, foreign firms were

granted the right to form sales alliances and in December 1998, to

market them directly.

Believing Japanese investors would be eager to achieve higher returns

through exposure to products like those offered in the U.S. and other

markets, foreign financial firms moved to expand their presence in

Japan. Merrill Lynch, for

example, acquired the failed Yamaichi Securities Co., Japan’s

fourth largest brokerage company, for about $300 million. With a national

network

of branch

offices and over 2,000 salespeople, Merrill sought to gain retail market

share.

Despite a major commitment and introduction of U.S. investment products,

training and business techniques, as well as a concerted effort to

localize themselves to better interact with Japanese consumers, Merrill

ultimately was not able to achieve the success they were looking for.

Therefore, by the end of the first year of this operation, Merrill

had less than half the Japanese assets under management than could

be found within the ¥625 billion held by Goldman

Sachs,

which catered to corporate and institutional clients..

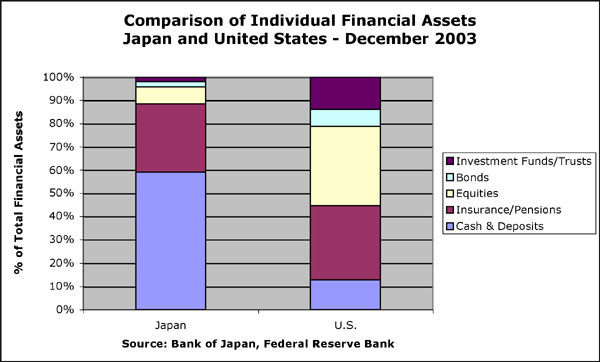

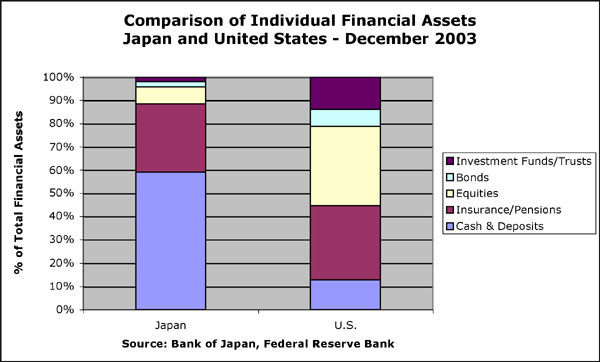

Japanese Preferred Security of Bank Deposits to the Risk of Equity

Investment

While the introduction of discount brokers and online Internet trading

has begun to change the nature of investing in Japan, the typical

Japanese retail investor, more than 50 years old, remains conservative

in their outlook. Many live in rural areas and equate the stock

market with a casino. Exhibiting a distinct preference for earned

over unearned income, they have found it hard

to distinguish between investment and speculation. These perceptions

were only reinforced when the nation’s “bubble economy” burst

in the early 1990s. Furthermore, unlike the U.S., Japanese culture

precludes many investors from revealing personal information until

they have established a close relationship with the requestor.

Most Japanese were also unfamiliar with the long-term, buy-and-hold,

index-style investing that led to the dramatic growth of retail investing

and mutual fund assets seen in the U.S., and the U.K. Customers were

also used to brokers making house calls, and providing a very high

level of service, especially to high-income households.

Their apprehensive and conservative attitude made it difficult for

them to consider alternatives, especially from foreign companies.

As a result, they preferred the security of guaranteed bank deposits

and especially that of the PSS, even though this resulted in annual

interest rate returns of less than 1%.

Part

of the reason so much money was placed in the PSS was that there

were advantageous tax benefits. For example, in

the past interest on postal savings was tax exempt. This has now

been changed to a limit of ¥3.5 million, after which interest

is taxed at an incremental rate of 20%. Since the PSS also receives

subsidies from the Japanese government, however, it has been able

to offer higher interest rates and fewer restrictions on accounts

than private banks. Furthermore, in uncertain economic times, the

PSS was also seen as being more secure and less risky than private

banks..

|

Financial Reforms Helping to Strengthen

Japanese Banking Institutions

|

| |

At the same

time, Big Bang reforms are bringing about heightened competition. New

financial policy tools geared to initiate "prompt corrective action" are

helping to gauge the soundness of individual firms and banking institutions.

As a result, financial institutions with low capital adequacy levels

have been required to improve their condition, lest a new administrative

organization known as the Financial

Supervisory Agency (FSA),

moves to issue directives designed to improve, or even to close, their

operations. Foreign private equity investors including Ripplewood,

Cerberus, Lone Star and WL Ross

also entered the sector. They introduced western banking practices,

including better

use of technology and decision-making based on credit analysis rather

than collateral and personal relationships. This has helped to raise

banking standards and performance in domestically-owned institutions

as well.

Over time these measures helped to initiate significant change. As

a result, in FY 2003, after ten consecutive years of operating losses,

the industry has begun to again achieve profitability. The latest data

provides further evidence and this year three of Japan’s top

four banking groups, Mitsubishi

Tokyo

, Mizuho and

Sumitomo

Mitsui , announced

they had been profitable for the first six months of FY2004

and expect to meet the government’s March 2005 deadline to reduce

their non-performing loans by 50%. A fourth group, UFJ

Holdings, reported a loss, and rather than take the risk

of violating Bank for International Settlement (BIS) requirements,

is now in the process of being acquired by Mitsubishi Tokyo. This is

likely to further reduce excess capacity in this sector.

Deposit-Guarantee Limits Marks a Major Additional Reform Measure

Japanese citizens have enjoyed unlimited government guarantees on banking

deposits since 1996. This was intended to build confidence in the banking

system, yet has had the unfortunate side effect of allowing the Japanese

public to ignore the underlying stability and health of the institutions

to which they entrusted their funds. As a result, banks could engage

in unsound and unprofitable practices and face little scrutiny from

depositors who remained sure their funds would be repaid through the

existence of unlimited government guarantees, regardless of the amount

or circumstances.

Realizing this only resulted in irresponsible behavior, in April 2002,

the Japanese government imposed guarantee limits of ¥10 million

(about $100,000) on time and installment savings deposits. Next year,

in April 2005, guarantees on all interest-bearing demand deposits in

private banks—money that can be withdrawn at any time— will

become subject to the same limit as well.

This move is likely to have important structural consequences as Japanese

banking customers will no longer be able to ignore the health of the

institutions to which they entrust their funds. The banks themselves

will also have to demonstrate their underlying health if they are to

retain their depositor base. Finally, Japanese investors will no longer

be able to simply deposit all their funds into a bank under the assumption

they are 100% guaranteed by the government.

Combined with a general need to seek higher returns as more Japanese

citizens advance into retirement age, as well as creative marketing

by stronger institutions, this is likely to increase general awareness,

and the perceived attractiveness of different financial instruments

and products. Government institutions are also moving to encourage

this transition and are considering tax reforms and other measures

to encourage investment into equities, trusts and other financial securities.

For example, dividends are currently taxed at a 20% rate, the same

as interest from bank deposits or fixed income securities. Capital

gains, however, had been taxed at a higher 26% rate. This is now

recognized as being discriminatory toward equity investments and steps

are being taken to lower this rate to the

same 20%.This will all help to deliver some of the changes in investor

behavior that had been forecast when the Big Bang reforms were first

initiated.

|

Privatizing

Japan’s Postal Savings System is the Next Reform Challenge

|

| |

Junichiro Koizumi was elected Prime Minister of Japan in 2001, winning

a popular mandate to lead the country out of a decade of economic stagnation.

Perhaps his most ambitious goal has been to privatize Japanese postal

services, which includes Japan's PSS. The PSS deposit base currently

totals approximately ¥350 trillion or $3.3 trillion ( ¥230

trillion in savings and ¥120

trilliion in insurance).

This accounts for over one third of Japanese household deposits and

makes it the largest financial institution in the world. It is about

2.5 times the size of Citigroup,

and about 20 times that of Postbank, the banking subsidiary of Deutsche

Post.

It also holds about a 30% share of the Japanese life insurance market.

Postal deposits, life insurance premiums, and other sources of funds

support an extensive system of government programs funded through the

Fiscal Investment

and Loan Program (FILP).

The ¥400 trillion in assets currently held by the FILP is more

than the total of Japan's four largest private banks. The FILP was

created a half century ago, gathering funds from asset-rich sources

such as the PSS and pension reserves via internal sales of Japanese

Government Bonds to finance necessary public projects, While these

initiatives helped to develop the infrastructure that enabled Japan

to become the world’s second largest economy, over the past decade

or two they often could not be justified as efficient uses of capital.

Many projects were approved, which while perhaps serving as short term

measures to stimulate domestic activity during periods of economic

recession, also introduced longer term distortions to the Japanese

economy and rising public sector debt that ultimately must be repaid.

In the past, the PSS also received preferential treatment. From the

consumer perspective, Japanese savers were not charged any tax on interest

gained from PSS holdings. In addition, unlike private banks, this institution

is exempt from corporate taxes and pays no risk premium to the deposit

insurance fund. Furthermore, only private banks are scheduled to lose

the unlimited government guarantee on demand deposits next year. As

a result of these advantages, the PSS attracts a huge amount of household

assets. Given that public confidence in private banks is only now being

restored, postal savings assets have steadily increased for over a

decade.

The current effort to privatize the PSS stems from a growing recognition

that the current system represents a major structural barrier to developing

a more efficient financial system in Japan. Change is essential to

allow the private sector to stand on its own feet and to develop a

banking and business culture that can efficiently allocate capital

according to market mechanisms and the basic tenets of modern credit

analysis.

To begin rectifying these imbalances, FILP assets have fallen over

the past ten years -- from about ¥40 trillion in 1995 to ¥20

trillion in 2004. Additionally, in July 2002, the government opened

up postal services to competition for the first time in 132 years.

Even more importantly, steps were taken in April, 2003 to form a new

entity, Japan Post, which will act as a holding company. Until that

time, the PSS was operated as a governmental agency. Under the new

system, a state-run business enterprise provides the four core postal

services. This includes mail delivery, management of individual branches,

postal savings, and postal life insurance. It marks a definitive shift

from an approach that relied upon allocated government funding to an

autonomous and flexible system based on market principles, as used

by a private business.

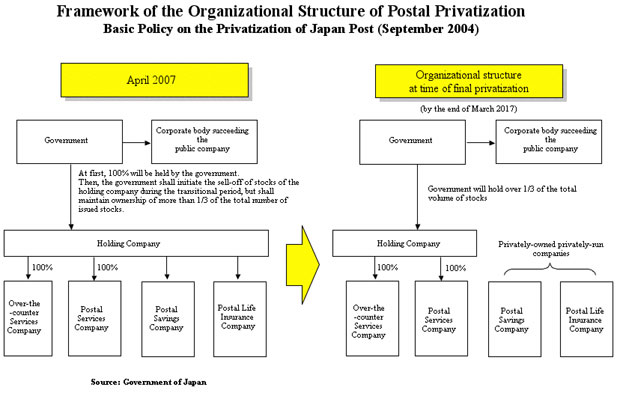

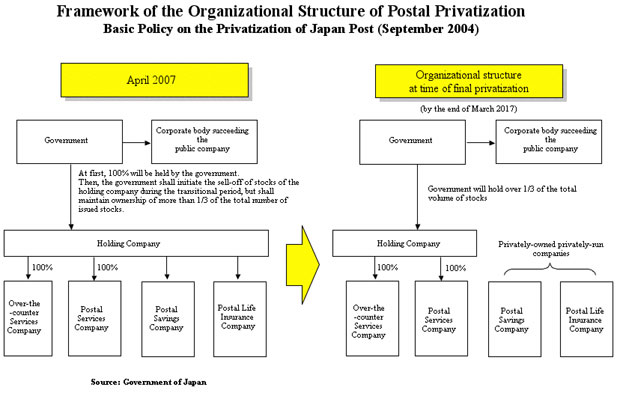

Basic Principles to Commence Postal Privatization Adopted in September

In September, the Japanese cabinet adopted the basic principles needed

to privatize Japanese postal services over a ten-year time frame. This

initiative will be led by the Japanese Prime

Minister’s office under the direction

of Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Heizo

Takenaka,

who successfully led efforts to cut nonperforming loans in major Japanese

banking institutions. Takenaka's ability to overcome the intense opposition

needed to require the banks to reduce their nonperforming loans by

50% makes him perhaps the most suitable person to take on this challenging

task.

Under this plan, Japan Post's four areas of service - mail delivery,

management of some 25,000 post offices, savings deposits and life insurance

- will become separate businesses in April 2007, each operating within

a single holding company. At that time, employees would lose their

status as civil servants and branches would be tasked with seeking

the best returns rather than supporting the subsidization of public

works projects. Privatization will then occur in progressive stages

over the following decade.

Privatization

of Japan’s PSS can be

expected to lead to the development of more sophisticated and efficient

financial and capital markets in Japan. This is true because the large

amount of funds that were previously directed into the public sector

through FILP or JGB’s will then be channeled directly or indirectly

into the private sector. That will make Japan’s national savings

a precious resource, which can be used to revitalize existing firms

and to help support emerging companies as well.

These changes are also likely to impact pricing in Japan’s large

government bond (JGB) market. Investor sentiment over these instruments

has led to the unusual situation where a Moody’s credit

rating upgrade of Japan’s four major banks last month

by as many as two notches to single-A-1, pierced Japan’s single-A-2

sovereign rating as a whole. A recent Dow Jones newswire article quoted

Moody’s Senior Vice President Mutsuo Suzuki on this situation,

who commented, (Japan’s) sovereign rating reflects “some

risks associated with the maturity restructuring” of JGB’s

in the years ahead. But “the…rating doesn’t necessarily

mean that the Japanese Government doesn’t have the financial

resources at hand to support these institutions if they need to”.

The realization that the fundamental credit strength of the Japanese

government and profitability of major Japanese corporations will

allow the nation to resolve any problems that arise is also reflected

in

another comment in this piece by Goldman Sachs Credit Analyst Takashi

Miura, who notes “Market attention will now focus on…an

upgrade for Japan sovereign debt”. Furthermore, Moody’s

Japan office highlights improvements in the financial structure of

private companies in the statement that “We are observing recovering

fundamental creditworthiness of many Japanese corporations, which has

led to and may continue to lead to upgrades”.

Contemplating the many difficulties at hand, however, has led some

analysts to criticize the Koizumi plan for offering too many compromises.

As a result, they doubt the government’s resolve. The American

Chamber of Commerce in Japan, for example, recently issued a report

that states the government’s effort risks enacting privatization

in name only, while maintaining real or implied government subsidies

and privileges for these new companies.

Others, however, suggest this misses the point. A recent Newsweek

account for example, quotes Tokyo analyst Stephen Church who states “… So

the outlook is that (the PSS) will actually disappear”. Once

that's gone, (Church) says, the government is betting that the privatized

bank will simply ‘melt in the sun like a snowman’ as consumers

shift their deposits to a new retail private-banking sector that will

begin to emerge in the spring of next year as the result of another

set of Koizumi reforms.”

The bottom line, however, is the Prime Minister and his team, including

Minister Takenaka, understand that Japan ultimately has no choice

but to take on this critical challenge. This is based on the clear

realization

that there cannot be irreversible reform and change in Japan without

the privatization of the PSS. As a result they must remain steadfast,

determined and dedicated to expending the political will and effort

needed to overcome any barriers that stand in the way. That is the

reason they consider it to be the “Centerpiece of Reform by the

Koizumi Administration” and perhaps the primary policy priority

over the remainder of their administration.

While many remain skeptical, in the words of a recent Far Eastern

Economic Review article covering the PSS privatization initiative: “In

the past, it would have been reasonable to expect little from such

a Japanese attempt at big change. But under Koizumi, (this) reform

looks to have a chance.”

|

The

Impact of Postal Savings Privatization is Potentially Enormous

|

| |

Placing

limits on demand deposit guarantees, first within private banks

and over time postal savings funds as well, should make Japanese

investors far more receptive to a wider range of investment

instruments than they have been in the past. These trends are already

in

motion, as noted by Michio Matsui, President & CEO of Matsui

Securities Co.

who recently commented that “Last year, equity trading

value (in Japan) increased tremendously, reinforcing the presence

of retail investors and their importance in the market. This

trend was led no doubt by online investors, and last year their

real presence was recognized for the first time (ratio of online

trading to total retail trading in 1st half of 2003 was 71% in

terms of trading value).” Furthermore, Japanese investors

accounted for ¥143 trillion of trading in FY 2003, up from ¥103

trillion the prior year, driving the biggest gain in the Topix

Index since 1973. In addition, the Tokyo Stock Exchange has

reported that Nomura

Holdings,

Japan's largest securities and investment banking firm, Daiwa

Securities Group and Nikko

Cordial were among 83 Japanese

brokerages that posted a profit for FY2003, against seven that

had losses. A year earlier, only 14 Japanese securities firms

were profitable.

Other notable online and discount brokers that cater to Japanese retail

investors include Monex,

Rakuten

Securities,

E*Trade and

Kabu.com. Furthermore, a recent Nihon

Keizai newspaper survey of 114 Japanese brokerages and

related firms found that 20 plan to offer online trading services while

33 others are considering this option. This is in addition to the 31

that already have Internet trading platforms. The potential growth

is enormous. Monex CEO Oki Matsumoto recently contemplated these developments

in an interview on U.S. public television stating “In the States

I think about 50% of the population own stocks and 36% trade stocks.

In Japan only like 10% of people own stocks and just 3% trade stocks.

It`s … a big space for us to grow into.”

If the Japanese public abandons the caution fostered by unlimited government

guarantees and preferential tax treatment, and over time begins to

invest their PSS savings in private banks and other investment vehicles

-- the country's economy will never be the same. Huge amounts of pent-up

household capital would be moved into private financial markets. This

would help to bolster not only Japan's incipient economic recovery

but, over time, financial markets around the world. Both Japanese and

foreign firms are moving to structure themselves to meet this need.

One example includes an alliance formed in 2000 between Monex and the

U.S. Vanguard Group, to market

Vanguard’s

mutual funds and investment products to Japanese retail and institutional

investors.

PSS privatization will push Japan to more efficiently allocate capital

and account for risk. As postal service privileges are removed, the

government will be forced to become more fiscally prudent. Since the

postal service would no longer be required to purchase government securities,

however, JGB’s would have to be sold to individual Japanese investors

and foreigners. At present, foreigners only own approximately 3.7%

of Japanese government debt. This low proportion has helped to shield

Japan from international market pressures. Individual households own

even less at 2.6% of the total.

If private investors and foreigners sharply increase their direct JGB

holdings, they are less likely to be forgiving about chronic budget

deficits. They will also need to perceive a risk-reward ratio that

effectively balances the ability of JGB’s to provide stability,

liquidity, diversification and Yen exposure with the interest rate

that is provided. This transition will be difficult and the resulting

upward pressure on interest rates does hold the potential to slow down

economic recovery in Japan. Some analysts believe this could result

in serious problems, yet others that it will be effectively managed.

Bloomberg correspondent, William Pesek, Jr., for example, reported

several months ago on a study by Christian Broda of the New York Federal

Reserve Bank and David Weinstein of Columbia

University. Pesek notes “Its basic

argument - that concerns about a Japanese public debt crisis are way

overdone - is filling in some of the blanks on how bond yields can

stay so low” and “the conclusion of Broda and Weinstein

is this: Don't panic. Japan's debt trends, they say, aren't unsustainable.

They further argue that (Japanese) government officials have ample

time and latitude to meet their obligations via higher taxes or reduced

benefits and services.” Pesek concludes the piece with his own

comment, that “Maybe investors accepting sub-2 percent yields

on Japanese bonds aren't so crazy after all.”

|

The

Resulting Funds Flows Have the Potential to Raise Global Equity Investments

|

| |

| |

Irreversible

reform of Japan’s PSS, the world's largest financial institution,

will mark a major milestone toward completing the economic reforms

and restructuring needed to restore Japan’s underlying economic

competitiveness.

Despite increased activity by retail and other Japanese investors, the

dramatic rise in Japanese equities that has occurred over the past year

has to a large extent been driven by foreign inflows. To cite one indicator,

inflows through November into Japan-related mutual funds are now three

times greater than inflows for all of 2003.

While there are many reasons for optimism over Japan’s future prospects,

the potential for a $3 trillion+ inflow into Japanese and other global

securities over a decade of postal savings privatization cannot help

but exert an additional positive influence. At the same time, it is true

that greater private foreign and domestic participation in the JGB market

will require a gradual transition away from the “zero interest

rate policy” which has existed in Japan since 1999.

For this reason Japan’s Ministry

of Finance is presently planning road shows for foreign investors

in New York and London next month. These events will be designed to familiarize

U.S.

and Europe investors with the government’s plans to privatize the

PSS, the investment potential of JGB’s, as well as other recent

trends and developments that have made Japan one of the best performing

and most attractive investment opportunities in the world over the past

year.

Coming

Soon: The next edition of JETRO’s Focus newsletter

will focus on recent events and trends as Japan enters the

new year. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

Data,

statistics and the reference materials presented within this newsletter

have been compiled by JETRO from

publicly-released media and research accounts. Although

these statements are believed to be reliable, JETRO does not guarantee

their accuracy, and any such information should be checked independently

by the reader before they are used to make any business or investment

decision.

|

| |

|

| |

For additional information on economic

and financial trends in Japan, please contact Akihiro Tada, Executive

Director of JETRO NY at Tel: 212-997-0416, Fax: 212-997-0464, E-mail:

Akihiro_Tada@jetro.go.jp

|

Focus:

Economic Recovery

Focus:

Entrepreneurship

Focus:

Consumer Demand

Focus:

Asia

Focus:

Gross National Cool

Focus:

Regional Development

Focus:

New Policy Challenges

Focus:

Investment Japan IV

Focus:

Investment Japan III

Focus:

Biotechnology

Focus:

Investment

Japan II

Focus:

Investment Japan

Focus:

Foreign Direct Investment

Focus:

Mergers & Acquisitions

Focus:

Entrepeneurship

Focus:

Economic Revitalization

Focus:

Industrial Revitalization

Focus:

Foreign Investment

Focus:

Bush Visit

Focus:

Koizumi Visit

Focus:

Economic Rebirth

Focus:

Hiranuma Plan

Focus:

Foreign Direct Investment

Focus:

Emergency Economic Package

Focus: Action Plan

Focus:

Economic Reform

Focus:

Okinawa Summit

Focus:

Small Business Development

Focus: New Enterprise Development

Focus:

Industrial Revitalization

Focus: Economic Recovery 4

Focus: Steel

Focus: Economic Recovery 3

Focus:

Economic Recovery 2

Focus: Economic Recovery

|

|

Focus is published and

disseminated by JETRO New York in coordination with KWR

International, Inc. JETRO New York is registered as an agent of the Japan External Trade

Organization, Tokyo, Japan and

KWR

International, Inc. is registered on behalf of JETRO New York. This material is filed with the Department of Justice

where the required registration statement is available for public viewing.

|