|

|

|||||||

| | ||||||||

|

|

Realizing the Potential of Central Asia: Interview with Michael Carter, CEO, Visor Capital, Almaty, Kazakhstan at Korea Financial Investment Seminar in Seoul, Korea

I am the CEO of Visor Capital, the leading investment bank in Central Asia. I am an American who has spent most of his life outside the US, mostly in Western Europe working in consulting and brokerage activities. In early 2007 I moved to Kazakhstan to be part of a team building a locally-owned investment bank with international level capabilities. From the beginning we had high ambitions -- to become THE partner in Kazakhstan for both international and domestic investors and corporates. We have, in spite of the current economic crisis had notable success in this effort. Our brokerage client base is mainly prominent institutional investors, and our investment banking business also serves international and domestic clients. With the promising resource based economy in Kazakhstan, and a good investor climate, we expect continued strong interest on the part of international financial and industrial investors.

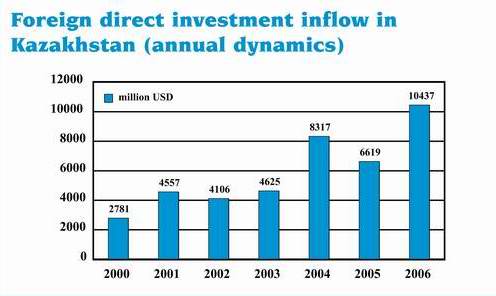

I am in Seoul to speak at a KOFIA sponsored conference on Kazakhstan. Korean companies and institutional investors are trying hard to diversify their exposure, particularly in the emerging markets. We believe we can help these institutions in their efforts in Central Asia. Central Asia is a region that drew a lot of attention with the fall of the Soviet Union and subsequent transition into newly-independent states. Since that time we have heard relatively little other than that the region possesses a lot of natural resources. Recently, however, we have begun to see a renewed interest in the region from both government and private sector contacts and clients. Can you talk about Central Asia and the opportunity it represents? Are you also seeing more interest in your own work? Although all Central Asian countries were historically part of the former Soviet Union, nowadays they greatly differ in terms of GDP per capita, resources, education, etc. Resource-rich Kazakhstan has experienced the fastest economic growth. Not only is this due to its resources, but also to the country's ability to set up a relatively stable business environment. This has enabled large companies such as Chevron, Exxon, ENI, Total, Areva, Kazakhmys, ENRC, KazMunaiGas, to extract these resources. It is quite significant that oil production has been increasing every year during the past decade, and that Kazakhstan has rapidly become the largest uranium producer in the world.

The situation in other Central Asian countries is very different: Uzbekistan, which was expected to become the regional power when the former USSR collapsed, is lagging behind, despite its larger population, and many observers have noted the business environment is severely constrained there. Kyrgyzstan has a very small GDP and has faced recent political troubles. Tajikistan is the poorest state in the region and lacks easily accessible mineral resources. Finally, Turkmenistan can be characterized as the "outsider". The country is still closed and lacks infrastructure yet it has tremendous untapped gas reserves and significant oil fields where production could ramp up in the coming years. As you see, every country is unique in this region; although so far the most interesting for investors remains Kazakhstan. Our firm has been quite busy during the crisis and we are seeing more projects that involve the capital markets and more public-market investor interest of late. Some people describe Central Asia and Kazakhstan itself as a land-locked Australia. Is that an accurate description? How should we view it from a political risk viewpoint? What is its present relationship with Russia and other neighboring powers such as Turkey, China and India? What is its present state of infrastructure, and should it be seen more as a region through the evolving prism of institutions such as CAREC or as a collection of individual countries and markets?

Kazakhstan is the world's largest country with no direct access to the open sea. The comparison with Australia works only for the amount of resources available in the underground. Also, large parts of some countries such as Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan are deserts or semi-deserts, so water supply is an issue. Almost everything else differs. In general, Central Asian countries lack infrastructure, though Kazakhstan is catching up rapidly. There is more electricity production being developed, railway networks being renovated, new motorways from China to Europe being built, to name a few initiatives underway. Kyrgyzstan is very much dependant economically on Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan has strong economic and historical links with Russia and a vast majority of the population speaks Russian and China has become a large investor in the commodities sector). So all in all, one might consider Central Asia as a collection of countries, but with historical and cultural links. Out of all the region's countries, Kazakhstan has been the most adept at cultivating successful relationships with both Russia and China, as well as the USA and Europe. One of the more interesting trends in recent years is firms in the US, Europe and Developed Asia now recognize the ability of emerging economies to deliver demand-led revenue growth -- rather than serve only as platforms to source commodities and lower production costs. Acting on this recognition is not easy, however, particularly for small and mid-sized businesses who lack the resources of large multinationals. Therefore, while we are spending a lot more time helping companies to better understand and set up operations in these markets, most who do take the step seek to focus their attention on China, India and Southeast Asia. How does Kazakstan and Central Asia compare to these markets? .jpg)

Kazakhstan is, and is likely to remain, primarily a resource-focused country, with a sparse population of only 16 million people. Therefore it is a limited consumer market. However, significant potential arises for supplying large infrastructure projects and downstream processing of commodities. Also, a services industry is developing around the large commodity projects. This includes hotels, education/training centers, catering, medical services and construction. Relatively limited competition in some segments makes them highly lucrative for players that can establish a market presence. It should be noted that wages in Kazakhstan are significantly higher than in the rest of Central Asia and that logistical challenges would tend to limit many businesses to regional markets. The World Bank recently rated Kazakhstan between Spain and Luxembourg in terms of the ease of doing business there. Is this justified? What is the cost structure of doing business in Central Asia?

Doing business Kazakhstan is much easier than in any other country in Central Asia, and probably Russia. Of course, there are still many things to be done in terms of legislation and acceptance of Western standards. In particular, investors should always remember that this is a post-Soviet country with an Asian culture. But the country has a lot of advantages, including a reasonably low tax rate for both companies and individuals, tax incentives for new businesses, the possibility of engaging with decision makers, the willingness of the authorities to develop the country economically with long term goals, etc. So the overall the ranking of the World Bank is not that surprising. Many multinationals have located their regional activities in Kazakhstan, not because of logistical simplicity, but because of the business environment. One of the more interesting findings covered in your presentation was the severe effect of the recent financial crisis on financial institutions in Kazakhstan, though it does seem like there is a real divergence between the financial sector and the real economy. Is this an accurate view? What happened to banks in Kazakhstan and how are they changing as a result? How far along are they to recovery, how dependent is this recovery on overcoming problems in Europe, the US and other advanced economies and how have these troubles effected the overall investment and business environment? Kazakh banks have generally little direct exposure to the parts of the economy that have recovered the most: oil & gas, and metals & mining. While that may sound unfortunate, it makes a lot of sense, because the banks do not want to take on exploration risks, which is more appropriate for equity investors. Producing resources companies, on the other hand, are actually a source of cash, placing their excess liquidity into the banks. When they do need cash however, many of these companies can find cheaper funding through international debt markets.

The unfortunate side is that the banks are exposed to the parts of the economy for which the recovery has been slower, with the most troublesome segment being construction and real estate. After the crisis of the late 1990s, the Kazakh banks grew with a CAGR of over 50% until 1H2007. The later part of that growth was largely fuelled by international wholesale funding markets, which helped to finance a significant real estate bubble in Astana, the capital, and Almaty, the main financial hub and largest city. Kazakh banks suffered quickly and acutely when foreign debt markets began to freeze due to the subprime crisis. After the world crisis deepened in 3Q2008, and the real estate bubble substantially deflated, the government injected capital into the four largest banks to prevent further problems. Now, the last of three banks are expected to emerge successfully from debt restructuring by September, and a macroeconomic recovery is well under way, and the sector is moving in the right direction. Do you see Kazakstan and Central Asia as being more of an opportunity for financial or corporate investors? Is it more of a green-field or a brown-field story? How do opportunities differ for these two classes of investors and what should each be looking for?

Both categories of investors can benefit from rapid expansion in the resource sector. The scarcity and lack of liquidity of industrial sectors make them harder to invest into. It is probably easier for corporate investors to invest in some segments by building a new plant with tax exemptions than for financial investors to find the opportunity and the right liquidity to invest in those segments. But there is no golden rule. In any case, it is of paramount importance to have a reliable local partner. You recently helped to engineer an acquisition of Bank CenterCredit by Kookmin, South Korea's largest bank by both asset value and market capitalization. Can you tell us about this deal, both in terms of the motivation behind it and how it transpired? What other notable deals have occurred in recent years? Yes, Visor Capital advised Kookmin Bank on their acquisition of Bank CenterCredit (BCC), a mid-size Kazakh bank that had been seeking a strategic investor. BCC held a formal bidding process among a wide range of strategic investors seeking to enter the Kazakh market as oil prices were heading towards their peak. From the Kookmin Bank side, there were many factors that could have influenced their desire to enter the Kazakh market, including:

While Kookmin's timing on the deal was not ideal, as it was announced in March of 2008 as oil prices neared their peak, it was far better than that of Italy's UniCredit Group. In 2007, UniCredit paid over US$2.2bn (and over 4x P/B) for ATF Bank, a bank of similar size to BCC. ATF Bank has since underperformed, posting substantial losses, which forced capital injections from the Group. We estimate that Kookmin Bank spent ca US$720m for a 42% stake in BCC, to date, which is equivalent to about 1.6x P/B. Moreover, BCC has remained profitable in each of the past two years, during the depths of the crisis. How can financial investors best participate in the Central Asia story? What is the state of public and private equity markets in the region? Are there many ADR or GDR listings that can be accessed through US, London or other major markets? Are there many hedge funds focusing on the region? What about ETF's and mutual funds?

Private Equity is a very competitive market, but there are some opportunities. For instance, several companies have been listed too early, and now have stretched balance sheets as a consequence of the crisis and of a poor management. This creates opportunities for Private Equity investors looking for restructuring stories. The local stock exchange (KASE) is illiquid by European or Korean standards. But most of the major companies are listed abroad or have a double listing. GDRs of those companies are often more liquid than the shares trading on the local market. We do see prospects for government privatizations through listings in the coming years. Given the illiquidity of the domestic market, ETFs have yet to develop. What are the main obstacles to doing business and making investments in the region? What should foreign corporate and financial investors understand before they enter Central Asian Markets? What is the state of corporate governance and how have foreign investors been treated there?

Central Asia is different from any other market investors may know; and so is the way to conduct business. Bureaucracy is sometimes heavy, but not inextricable. Linguistic issues do exist. For example, in a 2-language contract, for example, English and Russian, the Russian version will prevail in case of a misunderstanding. Cultural issues should also not be underestimated, too. For companies investing in remote parts of Kazakhstan, the lack of infrastructure is definitely an obstacle especially during the winter, where weather conditions can be particularly harsh and compromise production and transportation of goods. In terms of governance, many companies still do no report financials in line with international standards. However, we have noticed a gradual improvement and the paradoxical effect of the crisis has been to ensure that some segments of the market -- especially banks -- are managed more efficiently and transparently. Thank you Michael for your time and attention. Before we conclude do you have any parting words you would like to leave with our readers. The best way to invest in the region is to find a partner whom you can trust, in good times but also in bad times. It is also important to invest with a longer-term view. There are many opportunities here, as the country is on the verge of a resource-driven economic boom. This interview is part of an ongoing series highlighting Asia-related business, trade and investment opportunities and issues. While the information and opinions contained within have been compiled from sources believed to be reliable, KWR does not represent that it is accurate or complete and it should be relied on as such. Accordingly, nothing in this article shall be construed as offering a guarantee of the accuracy or completeness of the information contained herein, or as an offer or solicitation with respect to the purchase or sale of any security. All opinions and estimates are subject to change without notice. KWR staff, consultants and contributors to the KWR International Advisor may at any time have a long or short position in any security or option mentioned.

KWR International Advisor Editor: Dr. Scott B. MacDonald, Sr. Consultant Deputy Editors: Dr. Jonathan Lemco, Director and Sr. Consultant and Robert Windorf, Senior Consultant Publisher: Keith W. Rabin, President To obtain your free subscription to the KWR International Advisor, Website content © KWR International |