|

|

THE

KWR INTERNATIONAL ADVISOR THE

KWR INTERNATIONAL ADVISOR May/June

2003 Volume 5 Edition 2

In this issue:

|

(full-text

Advisor below, or click on title for single article window)

|

|

See

your article or advertisement in the KWR International Advisor.

Currently circulated to 10,000+ senior executives, investors,

analysts, journalists, government officials and other targeted

individuals, our most recent edition was accessed by readers

in over 60 countries all over the world. For more information,

contact: KWR.Advisor@kwrintl.com

|

The Global Economy – Living in Fear

By

Scott B. MacDonald

Radical

Islamic terrorists strike at targets in Saudi Arabia, Morocco

and Israel, North Korea continues to bluster with its finger close

to a nuclear weapons trigger, Iran is attempting to develop its

own nuclear weapons program, and Iraq remains unruly, with the

rule of law still lacking in the country’s major cities.

The U.S. dollar is falling, the Euro and Yen are going up, and

one of Japan’s major banks appeals for government assistance

to stave off a failure. Economic data from Japan indicates that

a double dip recession is an increasing possibility, while trends

in Europe point to the same direction. The German economy is looking

at unemployment creeping over 11%, while the French government

must contend with fiscal slippage, the pressing need to bring

the pension and benefits systems cost under control, and the strong

hand of unionized labor being manifest in a major national strike.

The stock market euphoria that was evident in April and the early

part of May, is increasingly fickle. Although most investors really

enjoyed the long-deserved and distantly remembered “feel-good”

sensation of watching the Dow, NASDAQ and FTSE tick upwards, the

solid foundation for a sustained bull market – as well as

corporate health and increased capital spending are still lacking. Radical

Islamic terrorists strike at targets in Saudi Arabia, Morocco

and Israel, North Korea continues to bluster with its finger close

to a nuclear weapons trigger, Iran is attempting to develop its

own nuclear weapons program, and Iraq remains unruly, with the

rule of law still lacking in the country’s major cities.

The U.S. dollar is falling, the Euro and Yen are going up, and

one of Japan’s major banks appeals for government assistance

to stave off a failure. Economic data from Japan indicates that

a double dip recession is an increasing possibility, while trends

in Europe point to the same direction. The German economy is looking

at unemployment creeping over 11%, while the French government

must contend with fiscal slippage, the pressing need to bring

the pension and benefits systems cost under control, and the strong

hand of unionized labor being manifest in a major national strike.

The stock market euphoria that was evident in April and the early

part of May, is increasingly fickle. Although most investors really

enjoyed the long-deserved and distantly remembered “feel-good”

sensation of watching the Dow, NASDAQ and FTSE tick upwards, the

solid foundation for a sustained bull market – as well as

corporate health and increased capital spending are still lacking.

As we have stated before the economic recovery is going to be

gradual and painful. In the United States, the recession is over,

but the ability to construct a strongly sustainable recovery remains

a challenge. The consumer is tired and the corporate sector still

is not spending. Worse yet, unemployment hovers around 6%, making

it feel like as though the recession is still here for many Americans.

Adding to the sense of uncertainty, there is growing concern about

deflation, broadly defined as a reduction in the level of national

income and output, accompanied by falling prices. It has been

partially caused by excess capacity in industries from automobiles

and telecommunications equipment to banking and airlines. Another

factor is the manufacturing machine that China has become: China’s

cheap labor and exports have forced many other manufacturing countries

to lower their prices to remain competitive.

While a little bit of deflation is not necessarily a bad thing

as it can balance past bouts of inflation (or hyperinflation in

some parts of the world), the fear is that the current type evident

in Japan and Europe could make things much worse in the United

States. If the U.S. economy slips into a new recession, the already

struggling global economy will stagnate.

What must be done to put the global economy back on track? First

and foremost, the U.S. economy needs to maintain growth above

2% in 2003 and increase that pace in 2004. For that to occur some

form of tax reform/budget stimulus must pass the U.S. Congress

and be implemented, interest rates remain accommodative (we expect

one more cut in June), and capital spending resume (this may be

the toughest to occur).

Equally important, but in a medium term timeframe, Europe needs

to regain some degree of economic momentum. This implies a more

accommodative stance by the European Central Bank -- which has

been more obsessed with inflation -- a willingness to implement

badly needed, yet unpopular, pension and benefit reforms, which

are necessary due to demographic and fiscal pressures. It also

requires greater leeway on the fiscal front as the current EU

target of a maximum allowance of a deficit of 3% of GDP is clearly

not helping and can in fact be argued as a contributory factor

to growing deflationary pressures. Germany, in particular, is

vulnerable to deflation – it lacks an ability to cut interest

rates, push up fiscal spending and its banks are in a weak condition.

Rounding out the picture, it is important that China continues

to grow at a rapid pace of above 6%. SARS has clearly put a crimp

in China’s strong GDP performance for 2003, but it could

also result in some positives for the Asian country in terms of

improving the national health care system and upgrading sanitation

practices. This would certainly help to contain SARS and reduce

the potential outbreak of new diseases.

As for Japan, the problems remain – a troubled banking system,

anemic economic activity, a large and mounting national debt,

and an embattled government seeking to move ahead on reforms against

entrenched opposition. We do not see Japan imploding, but the

economy will remain a challenge for the government and a point

of concern for the community of international policymakers. The

May government intervention in Resona Bank, which is a de facto

nationalization of the country’s fifth largest bank, does

provide an opportunity for the Koizumi administration to break

the logjam in the terms of the banking sector. It appears that

Resona’s top management is to resign, providing the government

with an opportunity to appoint reformers. If this transpires,

Japan’s fortunes could begin to look up.

The bottom line on the global economy and stock markets is that

we continue to live in fear. There is a long shadow looming over

the landscape – deflation. It is a major factor in Japan,

the world’s second largest economy, and it is increasingly

being mentioned as a point of concern in Germany and the United

States. The saving grace thus far has been that the U.S. economy

continues to grow – albeit far too slowly to remove the

fear factor. We still expect US real GDP growth of 2-2.4% for

2003, with a pick up to 3.0-3.3% in 2004. Key triggers going forward

include the passage of a stimulus-oriented budget in the US, interest

rate cuts in Europe and the United States, and some reduction

in global excess capacity. However, if the proper measures are

not taken in the United States and Europe, deflationary measures

on the global economy will mount. The nervous market over-reaction

to deflationary fears will become a reality and we will then really

be living in fear.

Will

the Dollar Remain Dominant?

By

Jane Hughes

The dollar has followed a rocky road in recent months, tumbling

to nearly $1.18 against the resurgent euro and to an anemic

119 yen, as foreign investment in both bricks-and-mortar and

portfolio investment in the States has ebbed. If the foreign

exchange rate is essentially the bottom line of the country,

then investor sentiment toward the once-mighty U.S. dollar –

and the economy that underpins it – is definitely cooling.

But while day-to-day currency movements remain well-nigh unfathomable,

there has been surprisingly little structural change in the

FX markets, even over the past decade. The dollar may be slipping

in value, but it continues to dominate the markets in other,

perhaps even more important, ways. The arrival of the euro in

1999 was supposed to herald a new era in which dollar dominance

of the FX arena gradually gave way to a more equitable distribution

of power among a tri-zone currency world (dollar, euro, and

yen). This has not happened. According to the most recent report

by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) on FX market

activity, published in 2001, within the tri-zone world the dollar

still reigns supreme. A whopping 90% of all currency trades

still include the dollar on one side of the deal; by contrast,

the euro figures in just 38% of all FX transactions.

The potential for internationalization of the euro – its

use in transactions not involving the 12 component countries,

and therefore its ability to challenge the dollar’s dominance

of global FX markets – remains murky. As a general rule,

this potential may be assessed in three ways: the euro’s

use as a medium of exchange for Europe’s trade with non-European

countries; its role as a store of value for stocks and bonds

on world capital markets; and its use in official FX reserves

held by the world’s central banks.

By these yardsticks, the picture is mixed.

-

Role in world trade: The U.S. accounts for only 14% of world

trade, but the dollar is used to invoice close to 50% of the

world’s exports. Clearly, there is room for the euro

to play a much bigger role in world trade. Countries with

close political, economic and financial links to the eurozone,

like those in central and eastern Europe as well as some former

colonies in Africa, may move toward the euro as an anchor

currency. This would result in the emergence of a broader,

informal “eurozone” encompassing countries well

beyond its official limits.

-

Role on international capital markets: The introduction of

the euro, clearly, is playing a big role in broadening the

depth, liquidity, and appeal of European capital markets.

In 1999, euro-dominated bonds accounted for 45% of all bonds

issued on international markets, slightly outstripping the

42% of bonds issued in dollars. This could presage the evolution

of the euro into a safe-haven currency over time, as investors

assess the strength and stability of the euro as well as the

credibility of the European Central Bank.

-

Role

in official reserves: The dollar accounts for 57% of global

FX reserves, and central banks have been loath to trade

in their dollars for euros thus far. Political issues may

eventually hasten this movement, but the huge bulk of FX

reserves held in Asian central banks (China alone is holding

around $200 billion) are conservatively managed. Given the

initial weakness of the euro, and lingering doubts about

the long-term viability of European monetary integration,

it seems unlikely that the euro will challenge the dollar

as a reserve currency for the foreseeable future.

So FX markets are still largely dominated by dollars. What

else has not changed on FX markets? The birth of the euro

led some observers (mostly French and German) to predict that

London would experience a gradual decline in its importance

as an international financial center, to be replaced by Frankfurt

and Paris. This, too, has not happened. London continues to

handle close to 1/3 of FX trading activities, far more than

any of its competitors, and the institutional skills and infrastructure

in the City of London command a hefty competitive advantage

in the FX business.

Trading in “exotic” currencies, too, was supposed

to take off. Faced with liberalization and deregulation in

emerging currency markets around the world – and faced

simultaneously with the need to replace lost opportunities

in intra-European currency trading – many traders looked

to exotic currencies as the next frontier. A decline in trading

activity and increased efficiency in markets for the mature

currencies of western Europe and North America (the euro,

after all, is entirely about removing market inefficiencies)

threatened FX trading profitability. Fortunately, at the same

time governments in Asia, central and eastern Europe, Latin

America, and even Africa were enthusiastically opening their

markets to foreign capital. The result seemed inevitable.

Or was it? In fact, the data on exotics market activity has

failed thus far to support the overheated rhetoric. According

to the BIS, trading in emerging market currencies comprised

just 4.5% of total FX market turnover in 2001, compared to

3.1 percent in 1998. So while trading in exotics is certainly

edging up, and is expected to play a greater role in FX trading

as the mainstream currencies get even older and stodgier,

the markets are still heavily dominated by trading in dollars,

euros, yen, and British pounds. (Indeed, trading in the three

main currency pairs – dollar/euro, dollar/yen, and dollar/pound

– accounts for close to 2/3 of total market activity.)

A few possible trends to watch for, then:

-

First, the possibility of a serious decline in market

liquidity is worrisome. FX market participants have complained

in the past couple of years that liquidity has become

erratic. The rise of electronic brokers, consolidation

within the banking industry, and the higher level of risk

aversion among global hedge funds all contribute to this

trend, and make it increasingly difficult to predict when

these pockets of illiquidity will occur.

-

Second, the FX markets may prove more herd-like than

ever, as trading business is more and more concentrated

among a few large players and the big macro hedge funds

play a cautious role. This may, in turn, presage more

sudden and dramatic currency swings.∑ Next, the

markets may prove more inexplicable than ever, stemming

from the growing influence of equities, and merger and

acquisition activity, in currency trading. Traditional

reliance on fundamental macroeconomic factors to predict

FX movements is increasingly discredited in this environment,

but it is far from clear what can replace this methodology.

-

Finally, trading volumes will probably rebound after

the period of consolidation at the end of the 1990s. Once

the fallout from the emerging markets crises of 1997-87

is fully absorbed and the euro finds its rightful place

in the markets, the inexorable march of globalization

and resulting rise in cross-border capital flows will

be reflected in higher turnover on FX markets. But buyer

beware: The larger and more unwieldy the market becomes,

the less responsive it will be to government intervention

– and the easier it will become for traders to destabilize

currencies of smaller and vulnerable emerging market countries.

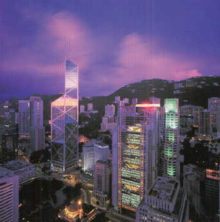

Hong

Kong – The Rise and the Decline of a Great City

That

the world’s economic geography changes from time to time

is nothing new and has been a common feature of human progress

and development throughout the ages. Herodotus already observed

in the 5th century BC that, “the cities that were formerly

great, have most of them become insignificant; and such as are

at present powerful, were weak in olden times”. In fact,

it is remarkable how uneven economic development has been since

ancient times with a great number of cities, countries and civilizations

having flourished and decayed – but at different times

and in different regions of the world. That

the world’s economic geography changes from time to time

is nothing new and has been a common feature of human progress

and development throughout the ages. Herodotus already observed

in the 5th century BC that, “the cities that were formerly

great, have most of them become insignificant; and such as are

at present powerful, were weak in olden times”. In fact,

it is remarkable how uneven economic development has been since

ancient times with a great number of cities, countries and civilizations

having flourished and decayed – but at different times

and in different regions of the world.

In early history the major clusters of wealth such as Thebes,

Babylon, Persepolis Nineveh, Bactria, and Samarkand were mostly

located around the Nile, Euphrates and Tigris rivers and along

the Silk Road. However, with the rise of the seafaring Phoenician

trading empire a shift in the centers of prosperity and power

toward the Mediterranean Sea took place, which led at different

times to the rise of cities like Athens, Tyre, Carthage, Alexandria,

Rome, and Constantinople, and finally culminated in the 15th

century with the first centers of capitalism – the Italian

trading cities of Venice, Florence, Pisa and Genoa. But, when

the Portuguese Vasco de Gama discovered in 1498 a new trading

route to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope and with the Spanish

conquest of the Americas, trading routes shifted away from the

Silk Road and the Mediterranean Sea, and threw Venice, as Montesquieu

observed, into a corner of the world where it has remained.

With the rise of the Portuguese and Spanish Empires and later

with the Dutch trading hegemony the clusters of wealth shifted

to cities like Lisbon, Cadiz, Antwerp and Amsterdam in Europe,

to Goa, Malacca, Macao and Batavia in the East, and to Mexico

City, Potosi, Lima, Bahia and Havana in the Americas.

The

Industrial Revolution and the rise of the British Empire in

the late 18th and early 19th century brought once again huge

changes in the world’s economic geography as cities such

as London, Manchester, Birmingham, Lancaster and Liverpool in

England, and Calcutta in the East displaced the old centers

of commerce, which had flourished under either Spanish, Portuguese

or Dutch rule. Then, in the late 19th century and especially

in the 20th century, the rise of industrial and commercial centers

in the US - first all located along the east coast but then

shifting to the Great Lakes region and the west coast displaced

the early English manufacturing centers.

Clearly, throughout the ages, economic growth and development

has been extremely uneven whereby major changes in the world’s

economic geography were driven by new inventions, discoveries

and social events. New inventions such as the compass, shifted

trading routes from land to sea and led in the 15th century

to the discovery voyages, which enlarged the world’s economic

sphere several-fold and relegated the until then rich Mediterranean

cities into a backwater. The construction of canals and the

invention of the steam engine, steel, railroads, tractors, cars

and electricity permitted the opening of landlocked territories

for agriculture and industries, which led to the rapid rise

of many totally new manufacturing and commercial centers, which

were landlocked, in the 20th century. New industries frequently

also increased the demand for commodities, which brought prosperity

to cities near large resource deposits such as Manaus for rubber,

and to Houston and Dallas for oil.

But throughout history cities did not only become rich because

of a favorable location, which was conducive to trade, the proximity

to skilled labor and abundant resources, which facilitated industrialization

and the exploitation of natural resource, and in the case of

Rome through sheer military power. What were also required were

a skilled administration, a well-established legal and commercial

infrastructure, low taxes, and most of all religious tolerance

and freedom, which attracted dynamic minority groups, and scientists,

artists, teachers, philosopher and inventors. Conversely cities

decayed because of internal and social strive, costly military

campaigns in order to maintain their trading empires or other

commercial interests, protectionism, their inability to adapt

to changing economic conditions, and intolerance towards minority

groups, which led merchant families or religious minorities

to leave.

Competition from the opening of new territories or from new

industries as well as infectious diseases was also frequently

an important factor. The Black Death caused by the Pasteurella

pestis, which made its first appearance in Europe at the port

city of Kaffa in 1346 when it was besieged by the Mongol leader

Kipchak Khan Janibeg who catapulted dead bodies into the city

(the first recorded case of biological warfare) quickly spread

to all the port cities of the Mediterranean and European trading

centers and reduced in the second half of the 14th century the

European population by close to 40%. The death toll from the

plague was naturally far higher in densely populated trading

ports and accelerated their economic decline. In fact it was

only in 1550, more than 200 years after the outbreak of the

pest at Kaffa, that Europe’s population again reached

pre-plague figures, whereby renewed plague epidemics ravaged

Venice also in 1575 and 1630. Or consider the economic and social

impact of the infectious diseases, such smallpox and influenza,

which were brought along to the Americas by the conquistadors.

Prior to the conquest by Cortez the Mexican civilization numbered

over 20 million, but the Aztecs lacking any acquired immunities

to the new infectious organisms were decimated within 50 years

to just 3 million!

We can therefore, see that Hong Kong suffers at present from

both a structural shift in the world’s economic geography

and a plague, about whose virulence and duration little is known.

Following the breakdown of the socialist and communist ideology

in China and the Soviet Union, and the end policies of self-reliance

and isolation on the Indian subcontinent the world’s economic

sphere was enlarged by as much as at the time of the discovery

voyages, since more than 3 billion people joined the global

market economy and capitalistic system. This means new competitors

for more recent centers of prosperity, such as Hong Kong, Taiwan,

South Korea and Japan, which benefited for as long as China

was a closed society under socialist policies. The same way

manufacturing shifted in the US from the East Coast to the Great

Lakes following the construction of canals and railroads in

the 19th century, the opening of China will lead to a massive

relocation of production, commerce and financial markets to

the mainland with Shanghai likely to regain the pivotal position

it enjoyed before the communist takeover, and other provinces

undermining the manufacturing sector of the Taiwanese, South

Korean, Japanese and Hong Kong economy.

In addition to this ongoing major change in the world’s

economic geography, which is also taking place in Europe as

a result of the breakdown of the Soviet Union, Hong Kong is

now increasingly vulnerable to infectious diseases whose most

fertile breeding ground is located in Southern China where humans

mingle densely with wild and domestic birds, and livestock.

Fortunate in the case of the 1997 bird flu, which could not

jump from human to human, and was, therefore, contained by killing

a million chicken, Hong Kong is now faced with its most serious

crisis since the 1967 riots due to the SARS causing virus, which

most likely jumped from pigs to humans but can now also be transmitted

among humans. Surely, Hong Kong will survive both the increased

competition from a large number of new commercial centers in

China and the SARS pandemic. But, these two major outside shocks,

which in the case of the increased competition from China will

not go away, and in the case of infectious diseases may recur

from time to time will likely reinforce the relative decline

of Hong Kong’ economic and financial power compared to

other cities in Asia and in particular in China.

|

|

FacilityCity

is the e-solution for busy corporate executives. Unlike

standard one-topic Web sites,

FacilityCity ties real estate, site selection, facility

management and finance related issues into one powerful,

searchable, platform and offers networking opportunities

and advice from leading industry experts.

|

EUROPE/MIDDLE

EAST

Putting the House in Order: Turkey’s Attempts at E.U.

Membership

Following the AKP’s (Justice and Development Party) overwhelming

victory in last November’s general elections, party leader

and now prime minister, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, promised sweeping

human rights reforms and economic measures to comply with the

EU’s political and economic criteria to enable Turkey

to begin membership negotiations. He believed that Turkey was

entitled to a date to begin talks since other candidate countries

had not fulfilled the criteria in full when they had begun their

respective negotiations. At the time, he stressed the mutual

interests of both the EU and Turkey, with the republic’s

membership as an example to the Muslim and western worlds that

democracy and Islam can co-exist. Erdogan also went so far as

to endeavor to implement outstanding rulings by the European

Court of Human Rights, identified as a serious issue by the

European Commission’s regular progress report on Turkey,

removing restrictions on freedom of expressions and conscience,

and allowing non-Muslim religious foundations to own real estate.

During December’s Copenhagen EU meetings, while the proud

Danish government concluded final preparations for the entry

of ten new member states, despite the best of intentions, the

Erdogan government discovered it would have to wait until December

2004 to learn if its planned reforms would meet the EU’s

criteria for membership. The European Council leadership resolved

to review Turkey’s progress on human rights, democracy,

and treatment of the Kurds prior to that date and would begin

negotiations "without further delay" if EU standards

in those and other areas were met. That resolution, in part,

arguably came about following the Turks’ withdrawal of

their long-standing veto over the use of NATO resources by the

EU military rapid reaction force. In the end, Erdogan reluctantly

accepted the December 2004 date, despite the Bush administration’s

strong lobbying tactics for a faster time-table for Turkey’s

accession. The Bush push had been urgently initiated in the

wake of the 9/11 tragedy and ahead of the then Iraqi invasion

plans as a means to demonstrate the benefits of reform to the

Islamic world. Also contributing to the Turks’ displeasure

was the EU leadership’s support for Bulgaria and Romania

to join the community by 2007.

The Treaty of Nice, signed in February 2001, created the framework

for the expansion of the EU. According to the criteria established

during the Copenhagen Summit in 1993, the timing of accession

of each country to the EU depends upon the progress it makes

in preparing for membership. These criteria include:

-

stability

of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human

rights, and respect for and protection of minorities;

-

the

existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity

to cope with competitive pressure and market forces within

the Union; and

-

the

ability to take on the obligations of membership including

the adherence to the aims of political, economic, and monetary

union.

While

aware of these strict criteria in relation to Turkey’s

recent economic, political, and social experience, the Erdogan

government realizes there is still much to do, although some

progress has been achieved.

The planned EU enlargement to absorb ten new member states will

create a trade bloc of twenty-five nations, a total population

of 450 million and an economy of $9.4 trillion, closely matching

that of the United States. Following a string of national referendums,

the ten candidate countries are scheduled to join in May 2004.

Soon thereafter, they will elect members to the European Parliament

and within the next few years, the majority, if not all, are

expected to adopt the Euro. The ten states are Malta, Cyprus,

Slovenia, Czech Republic, Poland, Hungary, Slovakia, Estonia,

Latvia, and Lithuania.

The EU’s 10 new member states may not welcome the prospect

of eventually sharing community transfer payments with Turkey,

a much larger country with a lower per capita GDP. Should Turkey

begin serious membership negotiations in early 2005, it may

not complete such negotiations for another eight to ten years

and by then it could have a population in excess of 80 million.

That would make it the EU’s largest member and among its

poorest. However, Turkey’s young population could arguably

become an advantage for the EU’s growing imbalance between

retirees and workers. Yet, its different cultural and religious

traditions would dramatically change the face of Europe.

Among the ten new members will be Cyprus, which has been divided

since 1974, when Turkey sent troops to repel a Greek-sponsored

attempt to take over the island that gained independence from

the U.K. in 1960. In 1983, the Turkish-held northern portion

declared itself an independent republic, but Turkey remains

the only nation that recognizes the separate union. A nine-nation

UN peacekeeping force continues to guard the 120-mile ‘Green

Line.’ Several attempts for a resolution of the partition

have failed, with the most recent occurring this March. Turkish

Cypriot leader Rauf Denktash then rejected a U.N.-sponsored

plan, championed by General Secretary Kofi Anan, that proposed

a combination of compensation and limited restitution to the

Greek Cypriots.

The talks failed because of disagreements over land and population

exchanges. That ended hopes of a united Cyprus that would join

the EU in May 2004. However, Turkey is now reportedly working

on a plan to transfer to a compensation board in the northern

part of Cyprus several thousand Greek Cypriot property claims

that would have otherwise been sent to the European Court of

Human Rights in Strasbourg.

As another positive measure, Erdogan surprisingly convinced

Denktash to lift the travel ban between the two regions in late

April. As a result, more than 300,000 people have since crossed

the ‘Green Line.’ The reported majority of the border

crossings have been made by Greek Cypriots visiting their former

homes, with most Turkish travelers seeking employment in the

south. Erdogan is reportedly ready to lift the trade ban on

Greek Cypriots and urged Greece and the world community to lift

trade restrictions that are economically strangling Turkish

Cypriots who have a per capita income of less than one-third

of the Greek Cypriots. Despite this gesture, he still insists

on the continuation of the two autonomous Cypriot communities.

Although Greece has backed Turkey’s bid for EU membership,

Turkey still fears that Cyprus, as an EU member, could veto

its eventual membership.

Six months after an overwhelming electoral victory, the AKP

has disappointed many as its experiment to reconcile Islam and

democracy continues to struggle. The party’s inexperience

and mistrust of the political establishment have prevented it

from reaching many of its reform goals. The authorities’

reported unsatisfactory response to the aftermath of the earthquake

on May 1st in the Kurdish majority province of Bingol, similar

to past governments’ tardy responses to natural disasters,

led to outcries from the opposition and clashes between police

and local demonstrators who were protesting shortages of tents,

food, and other emergency supplies.

As expected by many analysts, AKP-driven relations between the

secular state and Muslim society have become increasingly strained.

This was most evident when the division in parliament caused

the recent refusal of the U.S. request to deploy troops within

Turkey for the Iraqi campaign. AKP’s biggest challenge

remains the powerful military, which is very wary of further

reforms that would challenge its influence as the proud guardian

of Turkey’s secular traditions.

AKP carries the heavy baggage of the Islamic movement’s

previous failed attempt at democratic leadership. Erdogan’s

former mentor, Necmettin Erbakan, who also promised to respect

the republic’s secular system, found himself deposed by

the military just two years after becoming prime minister in

1997. Erdogan and others abandoned Erbakan and established AKP

on a political platform of democratic reforms with the goal

to achieve EU membership. The spotlight is also now on the AKP

to see whether it will act on its promise to pursue incomplete

IMF dictated structural reforms that were previously agreed

to by the former government. Those reforms range from mass privatization

to direct foreign investment schemes designed to eliminate two

of Turkey’s chronic ailments: the suffocating debt trap

and double-digit inflation levels.

Such an overhaul is paramount for Turkey to satisfy the EU’s

economic conditions, in addition to political criteria for membership.

It remains to be seen how successful the Ergodan government

will be in those efforts. We expect it to be a long road to

climb.

eMergingPortfolio.com

Fund Research tracks country/regional weightings and fund flow

data on the widest universe of funds available to emerging market

participants, including more than 1,500 emerging market and international

equity and bond funds with $600 billion in capital and registered

in all the world's major domiciles. http://www.emergingportfolio.com/fundproducts.cfm.

eMergingPortfolio.com also offers customized financial analysis,

data and content management services on emerging and international

markets for corporate and financial Internet sites. For more information,

contact: Dwight Ingalsbe, Tel: 617-864-4999, x. 26,

Email: ingalsbe@gipinc.com.

LATIN

AMERICA

Argentina: A Rock and a Hard Place

By

Jane Hughes

The

choice between former President Carlos Menem and leftwing

governor Nestor Kirchner in Argentina, the two presidential

candidates to qualify for the second round of voting, was

always depressing. The outcome is worrisome, too: Menem’s

abrupt withdrawal (in the face of certain defeat) handed Kirchner

a presidency that is tainted from the very beginning. At any

rate, now the course is set, so it is time for the markets

to render their verdict. The

choice between former President Carlos Menem and leftwing

governor Nestor Kirchner in Argentina, the two presidential

candidates to qualify for the second round of voting, was

always depressing. The outcome is worrisome, too: Menem’s

abrupt withdrawal (in the face of certain defeat) handed Kirchner

a presidency that is tainted from the very beginning. At any

rate, now the course is set, so it is time for the markets

to render their verdict.

The stock market actually dropped 8 percent the day after

the first round of voting, which set the stage for a second

round runoff between the widely discredited and unpopular

Menem – whose financial mismanagement is widely viewed

as paving the ground for Argentina’s financial collapse

of 2001 – and Kirchner, an unashamedly unreconstructed

Peronist whose economic plan actually drove business leaders

into the Menem camp. The denouement, giving Kirchner the presidency

without the legitimacy of an electoral win, can hardly be

viewed as a victory for Argentine democracy. In fact, the

peso fell by over 5 percent in the days following Menem’s

withdrawal, reflecting widespread dismay with the result.

Kirchner takes office on May 25 as Argentina’s sixth

president in 18 months; his mandate consists of the 22 percent

of the vote he received in the first round.

Kirchner’s record as a provincial governor and his candidacy

were unimpressive, too. Nothing in Kirchner’s career

as governor of an oil-rich province with less than 200,000

inhabitants has prepared him for the challenges that lie ahead.

In stark contrast to his fellow leftist Luis Ignacio da Silva

(Lula) in neighboring Brazil, Kirchner made little attempt

to reach out to business and foreign leaders who were unnerved

by his sometimes strident leftwing rhetoric during the campaign.

Kirchner’s economic plans are murky, but include:

-

A

pledge to demand that foreign creditors cut Argentina’s

overall debt, lengthen its maturities, and slash interest

rates;

-

Promises

of greater social justice and wealth redistribution;

-

Plans

to deepen the government’s import-substitution economic

model; and

-

A

commitment to give the state a bigger role in the economy,

partly by implementing massive job creation programs fueled

by government spending on infrastructure projects. He has

talked of a program to build three million new homes, which

will create five million jobs in an effort to bring down

the 20 percent-plus unemployment rate.

On

the positive side, Kirchner is taking over at a time when

Argentina’s much-battered economy is actually showing

some tentative signs of life. The country will run a healthy

trade surplus in 2003 (partially thanks to a more competitive

exchange rate), the budget is showing a primary fiscal surplus,

growth is put at 4% for the year (after an 11% decline in

2002), and there has been no sign of the much-dreaded hyperinflation

that accompanied past currency devaluations in Argentina.

Both the central bank president and Economy Minister Roberto

Lavagna – who is viewed as the man behind this burgeoning

recovery – have pledged to remain in office under a Kirchner

government.

However, much of this progress can easily be undone. Both

the trade surplus and the lack of inflation reflect, in large

part, the moribund state of the Argentine domestic economy.

Any revival in domestic demand – especially one fueled

by spiraling government spending, as Kirchner suggests –

is likely to invite both higher imports and higher prices

(not to mention a return to government deficits). Moreover,

Kirchner’s approach is unlikely to foster a prompt reconciliation

with Argentina’s foreign creditors, who are still reeling

from the country’s $95 billion default in December 2001,

the biggest sovereign default in history. Argentina cannot

move forward until the issue of its $170 billion debt, the

equivalent of nearly 140 percent of GDP, is resolved. With

the best will in the world, devising a repayment mechanism

will be unspeakably complicated – especially since more

than $55 billion of the bonds are held by overseas investors,

many of them retail investors.

Again, in stark contrast to Lula, Kirchner’s rhetoric

suggests that he may not have the best will in the world.

Under these circumstances, negotiations will be lengthy, intense,

and difficult. In the end, of course, Kirchner will have no

choice but to reach some accommodation with the foreign creditors

– but the process looks to be painful.

On the domestic front, Kirchner’s reputation as an old-line,

unreconstructed Peronist (a ‘party hack’ in American

terms) may also presage trouble. The deeply divided Peronist

party will find it difficult to sustain any kind of congressional

momentum, especially if the nascent recovery proves to be

short-lived. Kirchner’s uncertain mandate will buy him

little support in the congress, nor does he have any support

base among the country’s powerful provincial governors.

In this environment, Kirchner’s prospects for reforming

the deeply troubled domestic financial system – essential

if companies are to regain access to credit and jump-start

a real recovery – are also poor.

Despite all of Menem’s baggage, he probably would have

been the lesser of the two evils at this point in Argentine

history -- from the financial analyst’s point of view.

But the voters have turned their backs on Menem’s shady

past, and chosen to move forward with Kirchner. The best possible

outcome would be a Lula-style conversion for Kirchner once

he is in office. Optimists hope for a form of “smart

populism” that would vindicate the voters’ choice

and propel Argentina forward into the new century. As yet,

though, there is little sign of this. The worst outcome –

a legitimacy crisis that will remove Kirchner from office

well before his term is up – seems like a better bet.

Mexico – Increasingly Attractive Investment Fundamentals

By

Scott B. MacDonald

Mexico's credit fundamentals are improving – albeit

at a slower pace than in previous years. Reflecting this,

Moody's has recently changed the outlook to positive and

the Latin American country could benefit from any extended

complications with SARS in Asia. Mexico remains a relatively

low cost producer of many goods and has excellent proximity

to the U.S. through NAFTA. Despite the slight contraction

in first quarter 2003 real GDP, there are signs that parts

of the economy are beginning to gain momentum, a trend which

could strengthen when the U.S. recovery becomes more pronounced.

The Mexican economy is closely linked to the U.S. When the

U.S. economy slowed in 2001 and 2002, it took the Mexican

economy with it. Real GDP growth contracted in 2001 and

was weak (0.9%) in 2002. We expect the economy to expand

by 2.0-2.4% in 2003, with 3.5% growth possible in 2004.

The maquiladora sector, which has struggled over the last

two years, is beginning to see signs of recovery. The commercial

banking sector is also beginning to see an increase in activity.

Other key points to consider:

1.

Inflation forecasts are heading down. In early 2003, inflation

for the year was expected at 4.3%. The central bank's tight

monetary policy, however, is having a positive impact, as

consensus estimates for inflation have been lowered to 3.9%.

Considering that Mexico's inflation levels were well over

10% throughout the 1990s, this is positive news. For the

first 15 days of April, inflation was just 0.01%, the lowest

biweekly reading since April 2002. Inflation had picked

up in the late part of 2002 due to the steep depreciation

of the peso bled through into prices.

2. Retail sales were up 4.2% in February, well above expectations

and another sign that the worst of the recession may now

be over. Sales growth in basic consumer goods has been relatively

healthy for several months now. Big-ticket items have lagged.

After having fallen year-on-year for five of the six months

between August 2002 and January 2003, auto sales were up

a respectable 2.1% in February. It is expected that auto

sales are likely to continue to show ongoing strength in

March.

3. Higher than expected oil prices have been a major windfall

for Mexico and will help the government make its fiscal

target of a budget deficit equal to 0.5% of GDP. Higher

oil prices and better tax collection measures bore fruit

in the first quarter of 2003, as federal revenues rose 21%.

Mexico has now accumulated a 27.2 billion peso ($2.7 billion)

surplus. The government budget estimates the price of Mexican

oil will average between $23-24 a barrel, helping the state

to take in 14 billion pesos more in revenue this year than

initially forecast.

4. We expect Mexico's external accounts will remain off

of investors' radar screens. Mexico's current account deficit

will be equal to 2.5% of GDP, which should easily be financed

by foreign direct investment (FDI). It will also be an improvement

on 2002's current account deficit of 2.9% of GDP. FDI is

forecast at $14 billion for 2003. In addition, Mexico has

done its financing in the bond market already this year

and does not need to return.

5. There should be increased political noise as Mexico heads

to the July 6, 2003 congressional elections. However, the

political risk associated with the election is low. Both

the party of President Vincente Fox, the PAN, and the major

opposition party, the PRI, share a broad consensus on economic

policy. Indeed, the PRI long dominated Mexico's political

life and the last three presidents, prior to Fox, advanced

much of the structural reforms that provide the economy

its current foundation. Consequently, if the PRI were to

win the congressional elections in July this would not represent

a major shift in terms of policy. It could result in more

politicking between Congress and the Presidency in terms

of making deals to pass key legislation in the second half

of Fox's term. The PAN is coming in around 38% in opinion

polls over 37% for the PRI, while the left-of-center PRD

is polling around 20%. Such an actualization of the vote

would leave the Congress much as it now - an arena where

the PAN must form tactical alliances with the PRI to pass

legislation.

Mexico

has made considerable strides from the bad old days of debt

default during the 1980s. Although challenges remain, Mexico

remains one of the stronger sovereign performers, a trend

that should continue. The trick for Mexico is to maintain

fiscal discipline during the period that it takes the United

States economy to regain stronger and sustained momentum.

When the U.S. recovery eventually comes, the country just

south of the Rio Grande will be a strong position to take

advantage of improving macroeconomic conditions in North America.

BUSINESS

Japan’s Bio-Tech Venture: Tsunami or Just a Bubble?

By

Andrew H. Thorson, Partner of Dorsey & Whitney LLP

in Tokyo

In

the wake of an anemic economy and a short-lived boom in

e-commerce before the collapse of the global Internet bubble,

Japan’s national and local governments struggle to

retrofit the economy for the 21st century. While closing

companies outpace the number of new companies, national

and local governments are taking steps to encourage entrepreneurs

to develop new businesses. There are hopes that “bio-tech”

or “BT” can help to revitalize the Japanese economy. In

the wake of an anemic economy and a short-lived boom in

e-commerce before the collapse of the global Internet bubble,

Japan’s national and local governments struggle to

retrofit the economy for the 21st century. While closing

companies outpace the number of new companies, national

and local governments are taking steps to encourage entrepreneurs

to develop new businesses. There are hopes that “bio-tech”

or “BT” can help to revitalize the Japanese economy.

Regional Development of BT Industry

Japan’s Kansai region is hoping that BT can do just

that. At the heart of Kansai, Japan’s second city of

Osaka has been burdened by the national downsizing and the

hollowing-out of manufacturing industries. Kansai’s

unemployment rate outpaces Tokyo’s and as the region

struggles to redefine itself amidst vanishing jobs and businesses,

Kansai hopes BT ventures will spawn growth. At the center

of Kansai’s BT movement are projects such as the Kobe

Medical Industry Development Project (regenerative medicines

and medical devices), the Saito Life Science Park (new drugs

by genome and protein analysis), and the Wakayama Bio Strategy

(agriculture related BT). Kansai aims to be Japan’s

international life science hub.

It can be said that Kansai’s BT projects are not out

of character given the region’s existing pharmaceutical

interests. Roughly thirty percent of Japan’s pharmaceutical

industry locates there, including firms such as Takeda Chemical

Industries, Fujisawa Pharmaceuticals, Tanabe Seiyaku, Sumitomo

Pharmaceuticals, Dainippon Pharmaceuticals, to name a few.

Foreign interests have also established a foothold in the

region (i.e., Eli Lilly Japan, Nippon Becton Dickinson,

Bayer Yakuhin).

The Kansai BT base is supported by research seeds such as

Kyoto University, Osaka University, Kobe University and

The National Cardiovascular Center. Notable research facilities

located in the region include the Kobe Medical Industry

City, the Center for Advanced Genome Medical Research Development,

the Institute of Biomedical Research and Innovation (IBRI),

the RIKEN Center for Development Biology (CDB) and the Tissue

Engineering Research Center.

Opportunities for Growth and Investments

According to one survey, sixty-six percent of Kansai’s

BT firms and institutions seek a partnership with foreign

firms. Reasons for tying-up include joint research (both

commercialization and basic), technological alliances (licenses),

joint marketing and funding.

Private equity hopes BT ventures will crystallize into real

businesses and IPOs. One Osaka venture, AnGes MG Inc., receives

much attention as an early IPO success. AnGes MG listed

on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Mother Index last year.

While success stories remain few, Japan’s private equity

still anticipates successful BT ventures in Japan. According

to one source, the Kobe Biomedical Venture Fund has already

invested in at least 18 companies. The fund was established

in January 2001 to specialize in medical industries.

Biofrontier Partners, headquartered in Tokyo, also placed

bets on Japan’s BT industries. That firm, established

in 1999, was reported to be the first Japanese venture capital

firm to focus on life sciences.

It is hoped that BT will have spill-over effects in the

economy. For example, budding BT ventures may increase the

demand for support services such as drug design platforms,

BT-related devices and support services.

CAN ANYONE TELL US WHY JAPAN'S TECH ECONOMY IS BROKEN? Is Japan's high-tech economy broken? We don't think so. Derailed perhaps. But if you understand the mechanics, you can gain access to amazing opportunities for business and technology in Japan. Nobody else knows Japan like we do. Find out what's going on, direct from Tokyo, weekly and free. Four great newsletters at http://www.japaninc.com.

New

Tools for Private Equity

Outdated commercial laws and a shortage of legal and business

consultants familiar with high technology and Western-style

venture financing strategies plagued foreign investment

during the recent e-commerce venture boom. Japan’s

rigid legal system also failed to support flexible venture

tools such as certain types of employee stock option plans,

non-voting preferred stock, other creative stock classes,

granting of third party options, etc. Venture capitalists

found that their fast-paced business practices were stifled

by other incomprehensibly rigid formalities such as the

prohibition on board meetings by conference call.In the

wake of an anemic economy and a short-lived boom in e-commerce

before the collapse of the global Internet bubble, Japan’s

national and local governments struggle to retrofit the

economy for the 21st century. While closing companies outpace

the number of new companies, national and local governments

are taking steps to encourage entrepreneurs to develop new

businesses. There are hopes that “bio-tech” or

“BT” can help to revitalize the Japanese economy.

Japan’s Venture Spirit

In the late 90’s, Tokyo boldly compared itself to Silicon

Valley as a venture spirit took hold of Tokyo. In those

days Japan seemed poised on the edge of a venture capital

boom. The Shibuya Ward of Tokyo dubbed itself “Byte

Valley”. Salaried business persons questioned their

sunset careers at struggling trading companies, banks and

electronics manufacturers while friends moved to venture

companies, foreign PE and consulting firms, to ride Tokyo’s

new wave of VC activities.

Although “Byte Valley” died a young death it provided

precedent for a belief that Japan can embrace venture capitalism.

These days venture capital firms are not rare. There is

even a Nippon Angels Forum, which has held numerous sessions

in Japan attended by hundreds of investors. The forum has

opened in fourteen Japanese cities.

Perhaps the new wave of BT-venture is only a bubble right

now, but it could be a tsumani. Japan’s BT industry

is supported by a market said to be worth 1.33 trillion

yen in 2001, and second only to a U.S. market of 3 trillion

yen. By comparison, the combined European market has been

estimated at less than 2 trillion yen. Even under current

deflation, it has been estimated that Japan’s market

could grow at a rate of over 7% annually.

Andrew

H. Thorson is a partner at Dorsey & Whitney LLP in Tokyo.

His opinions may not necessarily reflect those of KWR International.

|

Buyside Magazine reaches active institutional investors monthly with news and analysis of the equities markets. Buyside takes readers beyond news of the current business climate to report industry and market trends that are crucial for investors to understand -- not simply the latest business trends or product releases. Buyside and BuysideCanada are available in print, and online at www.buyside.com. Subscriber information is available on Buyside's home page.

|

KWR

Viewpoints

Playing

Hard Ball: The Wisdon of Using Trade as a Foreign Policy Tool Playing

Hard Ball: The Wisdon of Using Trade as a Foreign Policy Tool

By

Russell L. Smith, Willkie Farr & Gallagher

During the 1993-95 confrontation between the Clinton Administration

and Japan over automobiles, the New York Times carried a new analysis

which quoted Clinton Administration officials (unnamed) to the

effect that if Japan persisted in refusing to grant measurable

market access to U.S.-built vehicles, the inevitable result would

be a weakening of both the economic and strategic relationships

between the United States and Japan. Even the hint that trade

conflicts could affect strategic relationships caused an uproar

in both countries. Administration officials were quick to deny

any such view, and Japan dutifully expressed its confidence that

the strategic relationship was as strong as ever and that even

the best of friends could have an occasional economic tiff without

its threatening their friendship.

A decade later, the current Administration has turned that equation

on its head, and is directly linking foreign policy and trade

policy in a series of actions that go far beyond anything contemplated

a few years ago. The most notable example is the delay in the

signing of the U.S.-Chile Free Trade Agreement after repeated

promises by three Administrations over the last decade that Chile

was “next in line” for an FTA. The Administration explains

that it signed the Singapore FTA but has been unable to complete

the Chile document because of English-Spanish “translation

delays.” Similarly, the Administration indicates that it

is unable to begin work on a U.S.-New Zealand FTA because of the

sensitivity of some of the products that could be affected by

those negotiations, despite the fact that those same products

have been the subject of a number of bilateral and multilateral

negotiations in recent years. Those two countries, of course,

withheld support for the U.S.-led “coalition of the willing”

against Iraq.

The economic conflicts and tensions between the United States

and the EU continue to increase almost daily. The latest is the

U.S. WTO case on genetically modified organisms, but that is only

one manifestation. The two trading partners are fighting over

taxes, steel, agriculture, aircraft, and assorted other sectors.

Those conflicts in turn threaten the success of the Doha Agenda

negotiations on multilateral trade liberalization.

Observers of the trade scene shrug their shoulders, claim “everybody

does it,” and conclude this kind of behavior is a reality

to be accepted. If this is true, it is a most dramatic and unfortunate

development in trade policy. While it is realistic to expect that

trade between nations whose relationships are openly hostile should

not be robust, and that there should be economic consequences

for such hostility, the same should not be the case when historic

trading partners and economic allies have legitimate, and even

difficult, disagreements over strategic policy.

This is particularly true in the present global economic climate.

The leaders of all developed countries, and at least the most

enlightened developing countries, have embraced the concepts of

open trade, multilateralism, trade liberalization, rules-based

relationships, and globalization. They say they are committed

to the principle that trade is the rising tide that floats all

boats. There are a few nay-sayers who claim that open trade retards

development, but in fact it is mercantilism and economic nationalism

that undermine the real economic progress that trade liberalization

unquestionably produces. Now we have added a third threat-- a

foreign policy which is not perfectly symmetrical with that of

the dominant trading partner.

Dealing with the effects of mercantilism and economic nationalism

is difficult enough without further burdening trade relationships

with the notion of punishing partners because they take certain

political stands. Whether one believes that Chile or New Zealand

took the right stand in opposing U.S. actions regarding Iraq,

both of these nations have essentially remade themselves into

market economies, abandoned decades of trade protection, and opened

themselves to outside investment. Their reward is to be brought

to the edge of the promised land of bilateral trade liberalization

and then told they may not enter. What message does this send

to other countries contemplating such actions? If it is that disagreement

with the United States over specific foreign policy goals cancels

out all positive economic initiatives, many nations will ask whether

the domestic economic upheaval is worth the risk. Other nations

will look for alternative opportunities from trading partners

who do not require political correctness as a prerequisite for

an FTA.

Ultimately economic and strategic relationships do go hand-in-hand,

but they do not develop through negative reinforcement. This does

not mean that recalcitrant nations should be coddled or condoned

when they close markets or undermine U.S. foreign policy. There

are trade rules for dealing with closed markets, and there are

diplomatic avenues for addressing foreign policy differences.

Going outside those rules and avenues to exact “rough justice”

by withholding trade benefits assures that both the economic and

strategic side of relationships will be weakened. The approach

was rejected a decade ago, and it should be rejected just as decisively

now.

Russell

L. Smith is a partner at Willkie Farr & Gallagher in Washington,

D.C. His opinions may not necessarily reflect those of KWR International.

Emerging

Market Briefs

By

Scott B. MacDonald

Cuba

– Still the Iron Hand: In March and April 2003 while the

world was focused the Iraq crisis, Fidel Castro, Cuba’s longstanding

socialist caudillo, flexed his regime’s muscles and clamped

down on local opposition groups. Although there has been speculation

as to the creakiness of the Castro regime, the authoritarian Caribbean

government demonstrated it was hardly down and out. In a well-planned

roundup, close to 75 independent journalists, human rights activists

and political opponents were arrested. Security forces charged

the dissidents with conspiring with the chief of the United States

Interest Section in Cuba, James Cason, and other U.S. diplomats

to overthrow the government. The crackdown was given extra severity

when three world-be hijackers apparently seeking to escape to

the United States, were executed by security forces.

The message from the Castro regime is clear – Fidel Castro

is still very much in command, has no intention to liberalize

the island-state’s political life, and regards the United

States as intent on intervening in Cuba’s affairs. While

local opposition groups were clearly cowered by the security crackdown,

the Castro regime was roundly criticized by much of the international

community. One casualty of the crackdown was a pending agreement

with the European Union (EU), which would have given Cuba preferential

terms for its products in the EU market. The EU had sought to

engage Cuba, even opening an office in Havana earlier in 2003.

The EU approach was that Castro could be induced by mutually beneficial

trade agreements and foreign investment to gradually open up Cuba’s

political system. Following the crackdown, the EU quickly signaled

there was no longer a deal on the table. The Cuban government

was highly critical, in turn, of the EU. However, it is the Cuban

people that ultimately suffer, especially considering the economy

is in bad shape, having expanded by only 1.1% in 2002.

Dominican

Republic – S&P Lowers the Boom: On May 15, 2003,

Standard & Poor's put the Dominican Republic’s BB- on

CreditWatch for a possible downgrade. The action was due to concerns

over emerging problems at Banco Intercontinental (the third largest

bank in the country), which could weaken political institutions

and the external reserve position and reduce financial flexibility.

Banco Intercontinental or BanInter has been a troubled institution

for a while, but in April the central bank was forced to intervene

after evidence of widespread fraud undermined plans to sell the

bank. Matters became even more murky when on May 13, 2003 BanInter’s

president was arrested and the government took over the bank’s

companies. The government also confiscated the assets of its troubled

bank’s major shareholders. S&P stated: “The ratings

on the Dominican Republic are constrained by low international

reserves, shallow domestic capital markets, and relatively weak

institutions and social indicators. The ratings are supported

by tax and social security reform programs and a low and favorably

structured public sector debt burden. Should these attributes

be undermined by the contingent liabilities posed by the financial

sector, a downgrade to B+ would be likely.” We expect the

government will scramble to resolve the problems related to BanInter,

though there are concerns that the corruption around the bank

could be deeper than currently anticipated.

Costa Rica – Outlook Less Sunny: Costa Rica has been

one of the more positive examples that a small country can broaden

its export base, upgrade its soft infrastructure (i.e. people

and their skills), and attract considerable foreign direct investment.

While Costa Rica benefited from this package of developmental

strategy throughout much of the 1990s and into 2000, the slowdown

in the U.S. economy has hurt. As the government has sought to

step in and help buffer the slower pace of exports, the fiscal

deficit has widened. In May, the IMF released its annual review

of the Costa Rican economy. While giving the Central American

country credit for a number of reforms, the IMF was critical about

the widening fiscal deficit, which could end up being equal to

4% of GDP in 2003. In 2002, the fiscal deficit was 5.4% of GDP,

a substantial number. This prompted the government to introduce

a tax package and tighten public spending. The government’s

fiscal deficit target is now set at 3.1% of GDP, which could be

a little too optimistic. Shortly following the IMF release of

the annual review, both Fitch and Standard & Poor's changed

their outlooks for Costa Rica from stable to negative.

Hong Kong – Reaching the Heights of Unemployment:

The last two years have not been kind to Hong Kong. Deflation

has become a major factor hanging over the economy, SARS has hurt

tourism and retail sales, and there is considerable discontent

with the government. The government estimates that tourist arrivals

declined 77% in April after the World Health Organization advised

travelers to stay away from Hong Kong. Tourism accounts for 6%

of the city’s GDP.

The most recent piece of bad news was that April’s unemployment

rate rose to 7.8%, matching an all-time high. The main culprit

was SARS, which kept consumers at home and drove away tourists.

There have been around 8,000 cases of SARS worldwide, with the

vast majority being in China, with Hong Kong having the second

highest tally of cases. Expectations are that unemployment will

most likely climb higher. HSBC and Standard Chartered Bank have

recently cut their real GDP forecasts for 2003 down to 0.5%. This

is a considerable slowdown from 2002, when the economy grew at

2.3%.

Jamaica – Problems Mount: In recent years Jamaica

has sought to implement structural reforms to make its economy

work better. However, 9/11, civic unrest and a number of natural

disasters have hurt the economy. In response the government of

Prime Minister P.J. Patterson has opted for fiscal stimulus to

keep the economy moving. This has caused the country’s debt

burden to climb. Jamaica’s debt expanded from 131% of GDP

at the end of the previous fiscal year to 152% this year. In April

the government advanced it budget, which included a J$13.8 billion

($246 million) tax package. Debt repayments will account for 65%

of budget spending this year. Both S&P (B+) and Moody’s

are negative on Jamaica’s outlook and in April the latter

put the country’s Ba3 rating on review for a possible downgrade.

Moody’s stated: “The review was prompted by Moody’s

heightened concerns over the Jamaican authorities’ apparent

lack of policy options to quickly correct the fiscal deterioration

that has occurred over the last 18 months.” We believe Jamaica’s

Ba3/B+ ratings will fall, probably to B1/B in the medium term

as tourism remains weak, international commodity prices (bauxite

and sugar being topical to the Caribbean country) will underperform,

and eventually interest rates will go up (most likely in 2004).

All of this bodes ill for Jamaica.

Singapore

– Adjusted Growth for Q1 Up: The Singaporean economy expanded

at a quicker pace than initially anticipated for the first quarter

of 2003 as exports compensated for a decline in domestic demand.

According to the Trade and Industry Ministry, real GDP for Q1

2003 was 1.1%, an upward revision from 0.7%. Unfortunately,

the expectation is the Q2 2003 will not be as strong due to

the negative impact of SARS on tourism and retail sales.

Uzbekistan – Call for Reform: At the close of the

annual meeting for the European Bank for Reconstruction and

Development (EBRD), that institution’s president, Jean

Lemierre, took the bold stance of calling the host nation to

adopt political and economic reforms. Without reforms, the Central

Asian country could face cuts in the EBRD’s financial support

in 2004. Lemierre did not mince words as he urged President

Islam Karimov to make radical economic and political changes,

in particular, the end of torture in Uzbekistan’s prisons.

In March 2004, the EBRD board meets to discuss lending to Uzbekistan.

If improvements are not made, the board will consider curtailing

funding facilities for the Central Asian government. This has

already been done in the cases of Belarus and Turkmenistan,

where authoritarian governments have blatantly suppressed political

freedoms.

Book

Reviews

Stephanie

Griffith-Jones, Ricardo Gottschalk, and Jacques Cailloux,

(Eds.) International

Capital Flows In Calm and Turbulent Times: The Need For New

International Architecture

(University of Michigan Press, 2003) Stephanie

Griffith-Jones, Ricardo Gottschalk, and Jacques Cailloux,

(Eds.) International

Capital Flows In Calm and Turbulent Times: The Need For New

International Architecture

(University of Michigan Press, 2003)

Reviewed

by Jonathan Lemco

Click

here to purchase "International

Capital Flows In Calm and Turbulent Times: The Need For New

International Architecture "

directly from Amazon.com

Following

the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, there have been several

efforts to explain the root causes of the event, and the lessons

we might learn from it. In fact, an excellent web sight maintained

by New York University Stern Business School professor, Nouriel

Roubini, offers a daily chronicle of the causes and consequences

of the crisis, and the various strategies devised to reduce

the likelihood of a re-occurrence.

In this edited volume, Griffith-Jones, Gottschalk, Cailloux

and their contributors offer an overview of the crisis, a

discussion of two other troubled economies at the time (Brazil

and the Czech Republic), and a consideration of the various

current proposals for a new “international financial

architecture”. By comparison to most edited volumes,

this one is more coherent and comprehensive. It is also well

written and fairly jargon-free. But we would stress at the

outset that it does not cover much new ground either, and

would be most appropriate for a senior undergraduate or first-year

graduate course in international finance or economics.

Much of the volume is devoted to a review of the apparent

causes and implications of the financial crisis in Thailand,

Malaysia, Indonesia, and Korea, as well as Brazil and the

Czech Republic. Particular attention is devoted to the role

of banks in lending, and mutual funds in investing in the

region in the late 1990s. This is fine as far as it goes.

The authors come to the reasonable conclusion that the Malaysian

policy of imposing capital and currency controls resulted

in mixed results overall, and the fundamental strength of

the Korean financial system allowed it to recover fairly rapidly.

A great deal of attention is devoted to the relative merit

of maintaining substantial official reserves, given the costs

involved. But there is agreement that as a preventative measure,

greater use should be made of both private and official contingency

credit lines. Also, these funds should be made available before,

rather than after, official reserves reach low levels.

The various articles in this book make the reasonable case

that high savings and investment rates do not prevent a country

from suffering a balance of payments crisis.

In fact, great deal of attention in the book is devoted to

the risks associated with contagion. That is well and good,

but we think that few strategies are suggested in this volume

to deal with this terrible problem. Further, little attention

is devoted to the moral hazard debate, which we think is central

to investor perceptions of the crisis.

On the other hand, the authors argue convincingly that better

regulatory measures are key to avoiding future crisis. Most

notably, they make the case that better international cooperation

is required to reduce the risks of future crises.

This is a solid overview of the Asian crisis and its aftermath.

It deserves to be read by scholars in the field. But this

will not be the definitive work on the topic.

Ian

Buruma, Inventing

Japan, 1853-1964, (New York: Modern Library,

2003). 192 pages. $19.95

Click

here to purchase"Inventing

Japan, 1853-1964, directly

from Amazon.com Click

here to purchase"Inventing

Japan, 1853-1964, directly

from Amazon.com

By

Scott B. MacDonald

For

anyone wanting to gain an easy access to Japanese history,

written in an engaging fashion (with no footnotes), there

is much to recommend Ian Buruma’s Inventing Japan.

The author, an accomplished fiction and non-fiction writer,

has studied and worked in Japan for a number of years and

clearly has a deep respect and liking for his subject matter.

In a series of biographical snippets, his essay follows

the dramatic transformation of Japan, beginning in 1853

with the arrival of Commodore Matthew Perry and the Black

Ships to 1964, when Tokyo hosted the Olympics, which symbolically

allowed the Asian country to rejoin the world following

the Second World War. While Buruma recognizes the darker

side of Japanese history, he focuses on the country’s

ability to catch-up with the West and to regain its role

in the world following the disasterous defeat of World War

II. He concludes that Japan is again at a troubled period

in its history, due to “a political establishment that

deliberately stifled public debate by opting for a monomaniacal

concentration on economic growth. And it is the result of

an infantile dependency on the United States.” Unlike

some Japanese who have argued that it would be good for

Japan to have new Black Ships shocking the country into

action, Buruma thinks the Japanese themselves clearly have

the ability to heal themselves and move. Altogether, a solid

and useful read.

|

Global Credit Solutions Limited provides a top-level service in the collection of commercial and consumer accounts, skip tracing, asset and fraud investigations and credit information on companies and individuals, globally. Visit them on the web at http://www.gcs-group.com or join their free monthly newsletter specially designed for credit professional and managers. |

Recent

Media Highlights

For

pictures and updates of our recent Japan Small Company