- U.S.

Market Outlook – Uncertainty and the Market

- Interview

with Dr. Marc Faber, lnvestment Advisor, Fund Manager and Author

- Korea

Needs to Address the Growing Uncertainty of International Investors

- Interview

on Japanese M&A Environment with Mr. Kiyoshi Goto, Director

General, Department of Business Development, Development Bank

of Japan

- Investing

in Japan Via Tax Efficient Silent Partnerships

- Ancient

History?: Thailand and Cambodia make peace – but for how

long?

- The

Global War on Poverty: An American Foreign Aid Revolution

- Consoling

Progress: How September 11 Affected U.S. Trade Policy

- International

Trade After September 11 - Port Security Initiatives and International

Business

- The

Canadian Tiger is Still Roaring

- Vietnam’s

Roaring Private Sector

- The

Political Economy of a Stronger Yuan

- China’s

Other Economic Agenda: Priorities, Progress, and Policies

- Intellectual

Property Rights, Pharmaceuticals, and East Asia: Turning Gold

into Lead?

- Malta

and Slovenia – A Growth of European Momentum?

KWR

Viewpoints

- The

Return of Spheres of Influence?

- French

Foreign Policy: A Perspective from History

Emerging Market Briefs: Brazil, Colombia, Israel, Malaysia, Peru

- Book

Review: Al-Queda: In Search of The Terror Network that Threatens

the World

- Book

Review: Saddam – King of Terror

- Book

Review: The Railway King: A Biography of George Hudson, Rail Pioneer

and Fraudster

- Media

Highlights

(full-text

Advisor below, or click on title for single article window)

Ilissa

A. Kabak, C.

H. Kwan,

U.S.

Market Outlook – Uncertainty and the Market U.S.

Market Outlook – Uncertainty and the Market

By

Scott B. MacDonald

The U.S. stock market remains in

a stage of high volatility, reflecting a deep-seated degree of

uncertainty over the future direction of global politics and the

anemic nature of the U.S. economic recovery. While the prospects

are good for a short-term equity rally based on the view that

the war with Iraq will be short, there remain many dark clouds

on the horizon. This threatens to bring dark days in the form

of a plunging stock market, new terrorist attacks on U.S. soil,

and the much-talked about double dip recession. With the Dow marching

back and forth over the 8,000 mark, there is a good case to make

that it could dip further, possibly below 7,000 before the end

of the year.

Why all the gloom? At the end of the day, the fundamental issue

is uncertainty. Markets hate uncertainty and we have plenty of

it. Although we do not see a double dip recession and believe

the U.S. economy is in a recovery mode, the pace and scope of

that recovery is not strong nor is it convincing. As we have stated

before, the U.S. economy is functioning like it did in the early

1990s. The actual recession, based on a contraction in GDP, is

over, but there was a lag before sentiment changed for the better

and recovery gained momentum. In 1991, the U.S. economy had a

mild contraction, but expanded moderately in 1992 and 1993. The

problem was that unemployment was high and for sectors of the

economy, recessionary tendencies lagged.

We see the same pattern at work now, though corporate debt is

higher. Although the U.S. technically did not have a recession

(as there was not a back-to-back quarterly contraction in GDP),

it has certainly felt like one and indeed the vast majority of

Americans regard 2001 (and early 2002) as a recessionary period,.

The problem is that the weak recovery is going to continue. The

danger is that the U.S. economic expansion could glide lower,

possibly stalling. The February uptick in U.S. unemployment from

5.7% in January to 5.8% should serve as a reminder that a very

real downside scenario continues to sit on the horizon.

Our major worries are ongoing concerns about the Middle East and

North Korea, the impact of higher oil prices (making itself felt

at the gas pumps and in home heating bills), and the weakening

consumer. Higher energy costs are certainly a negative for the

already battered airline and auto companies. Added to that is

the corporate sector’s reluctance to raise capital expenditures

until there is greater clarity vis-à-vis the economy and

geopolitical risks. Feeding on the uncertainty, banks and other

financial institutions are nervously looking over their loan and

credit card portfolios, though there has of yet been no major

spike in non-performing assets. [In fact, many regional banks

have reported non-performing assets of less than 1% of their loans

in Q4 2002.]

Yet, for all the potential negatives in the market, not all is

lost. Resolution of some of the geopolitical issues would go a

long way in reducing uncertainty. With a few exceptions, corporate

governance is improving. Sarbanes-Oxley is having a positive impact

in making management clean up balance sheets. Although the problems

at Ahold, the Dutch-owned supermarket giant were bad, it was the

company that approached the Securities Exchange Commission to

notify that agency that it had accounting problems. More significantly,

the large debt overhang from the 1990s boom is being pared to

more manageable levels and U.S. companies are much more cost-efficient

than before. Finally, technical factors in the U.S. corporate

bond market are strong – there is little new supply and a

lot of money sitting on the sidelines wanting for the war scare

to end and for companies to take advantage of very low interest

rates to refinance. The few deals that came in February and early

March were usually oversubscribed.

While we can be cautiously optimistic about the U.S. corporate

bond market, we cannot say the same about the stock market. Equities

have a long road ahead of them before we see another bull market.

Some of these speed bumps include:

-

Equity markets are no

longer the source of cheap capital for industry as they were

in the 1990s;

-

Corporate problems will

continue to have a quick and brutal echo in the stock market.

Companies that get into trouble, be it with accounting or corporate

governance issues, will be punished as investors will first

flee the name and then shun it;

-

Ongoing weakness in

the U.S. and global economies undermines any extended rally.

While the U.S. at least has a weak economy, with real GDP growth

in excess of 2%, the same cannot be said of the world’s

second largest economy, Japan, which is looking at 0.5-1.0%

growth in 2003 and Germany, the world’s number three economy,

which could slip back into recession.

-

The tech sector continues

to struggle, caught between the stark financial and economic

realities and the need to push ahead for new innovations. Venture

capital is hardly what it was in the 1990s and in most cases

is being treated like spare silver bullets;

-

While an Iraqi war may

play out quickly, geopolitical issues are not going to be entirely

eclipsed. North Korea remains an ongoing risk and al-Qaeda is

hardly been eliminated; and

- It will take a long time for small

investors to feel comfortable in investing in the stock market

in a major fashion due to the billions of wealth lost in the market

crash in 2001.

Consequently, we see the

Dow as having another bear year in 2003, probably falling below

7,000 at some point, before recovering. The following year could

see a recovery in stock prices, but that will depend on the ability

of the economy to move at a faster pace than the 2.4-2.6% range

and a decline in geopolitical uncertainties. Eventually the bulls

will return, but at this juncture they remain out in the pasture,

leaving the bears in charge of the street.

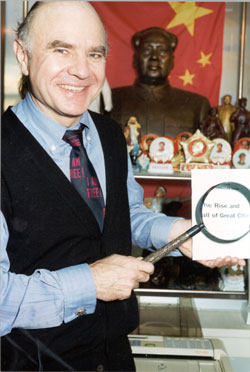

Interview

with Dr. Marc Faber, lnvestment Advisor, Fund Manager and Author

By

Keith W. Rabin

Marc

Faber was born in Zurich, Switzerland. He went to school in Geneva

and Zurich and finished high school with the Matura. He studied

Economics at the University of Zurich and, at the age of 24, obtained

a Ph.D. in Economics magna cum laude. Between 1970 and 1978,

Dr Faber worked for White Weld & Company Limited in New York,

Zurich and Hong Kong. Since 1973, he has lived in Hong Kong. From

1978 to February 1990, he was the Managing Director of Drexel

Burnham Lambert (HK) Ltd. In June 1990, he set up his own business,

Marc Faber Limited, which acts as an investment advisor, fund

manager and broker/dealer. Dr Faber publishes a widely read monthly

investment newsletter "The Gloom, Boom & Doom" report

which highlights unusual investment opportunities, and is the

author of the recently released book "Tomorrow's

Gold" and "The Great Money Illusion - The Confusions

of the Confusions" which was on the best-seller list for

several weeks in 1988 and has been translated into Chinese and

Japanese. A book on Dr Faber, "Riding the Millennial Storm",

by Nury Vittachi, was published in 1998. A regular

speaker at various investment seminars, Dr Faber is well known

for his "contrarian" investment approach. He is also

associated with a variety of funds including the Iconoclastic

International Fund, The Baring Chrysalis Fund, The Baring Taiwan

Fund, The Income Partners Global Strategy Fund, The Framlington

Eastern Europe Fund, The Buchanan Special Emerging Markets Fund,

The Hendale Asia Fund, The Indian Smaller Companies Fund, The

Central and Southern Asian Fund and The Regent Magna Europa Fund

plc and Tellus Advisors LLC. Marc

Faber was born in Zurich, Switzerland. He went to school in Geneva

and Zurich and finished high school with the Matura. He studied

Economics at the University of Zurich and, at the age of 24, obtained

a Ph.D. in Economics magna cum laude. Between 1970 and 1978,

Dr Faber worked for White Weld & Company Limited in New York,

Zurich and Hong Kong. Since 1973, he has lived in Hong Kong. From

1978 to February 1990, he was the Managing Director of Drexel

Burnham Lambert (HK) Ltd. In June 1990, he set up his own business,

Marc Faber Limited, which acts as an investment advisor, fund

manager and broker/dealer. Dr Faber publishes a widely read monthly

investment newsletter "The Gloom, Boom & Doom" report

which highlights unusual investment opportunities, and is the

author of the recently released book "Tomorrow's

Gold" and "The Great Money Illusion - The Confusions

of the Confusions" which was on the best-seller list for

several weeks in 1988 and has been translated into Chinese and

Japanese. A book on Dr Faber, "Riding the Millennial Storm",

by Nury Vittachi, was published in 1998. A regular

speaker at various investment seminars, Dr Faber is well known

for his "contrarian" investment approach. He is also

associated with a variety of funds including the Iconoclastic

International Fund, The Baring Chrysalis Fund, The Baring Taiwan

Fund, The Income Partners Global Strategy Fund, The Framlington

Eastern Europe Fund, The Buchanan Special Emerging Markets Fund,

The Hendale Asia Fund, The Indian Smaller Companies Fund, The

Central and Southern Asian Fund and The Regent Magna Europa Fund

plc and Tellus Advisors LLC.

Thank you Marc, for agreeing to speak with our readers. Can

you tell us a little about your background and current activities?

I am Swiss and have worked in the investment field since 1970,

first with White Weld & Co., later with Drexel Burnham Lambert

Inc. I have lived since 1973 in Hong Kong and formed my own investment

management and advisory company in 1990. I publish the Gloom Boom

& Doom Report (www.gloomboomdoom.com ) and have written several

books including the latest one entitled “Tomorrow’s

Gold”, which is available through Amazon.com.

Until recently the U.S. was perceived as a safe haven and in

many ways a beneficiary of global turmoil. This has been changing

due to U.S. economic and corporate excesses and the 9/11 tragedy.

As a result, investors have been enduring dramatic losses in dollar-denominated

assets. This would seem to argue for greater international exposure,

yet economists such as Joseph Quinlan argue that investor fear

exceeds their desire for greater diversification and outflows

from the U.S. -- have to date been minimal. Can you give your

thoughts on this and whether this trend will be sustained?

Most investors seem to be brain-damaged. They buy high and sell

low. They buy what is perceived to be safe or promising big returns,

not what will provide big returns in future. In the late 1980s,

they bought Japan and Asia and were negative about the US. In

the late 1990s right up to now, they bought the US and shunned

Asia, although Asia is following the crisis of 1997 relatively

inexpensive.

Alan Greenspan and many analysts have expressed the view that

current economic difficulties in the U.S. are largely the result

of "global uncertainty" and that once problems with

Iraq and other issues are resolved, positive growth and momentum

will be restored in the U.S. Do you believe that is the case what

is your outlook for the U.S. economy?

The problems of the US economy have nothing to do with “global

uncertainty”. Greenspan messed it up so royally that he

now has to find an excuse for his disastrous handling of the economy

over the last 10 years or so. Now, we are paying the price for

the ill-fated US belief that all problems can simply be solved

by easing, printing money and expanding credit. Mr. Greenspan

should never have been a Fed Chairman and future historians will

judge him very negatively.

Throughout much of the 1990s, there was a lot of discussion

about the "East Asian Miracle" and the coming "Pacific

Century". This talk largely evaporated during the 1997 Asian

financial crisis. Do you believe we were too quick to write off

the "East Asian Miracle" and does the "Asian Way"

represent a real alternative to Anglo-Saxon business and financial

practices?

I do not believe so much in stereotype phrases like Asian miracle,

the Asian way, etc. When it comes to money all people are of the

same religion. In Asia, we have in theory looser controls over

the economy than in the West, but recent events in the US and

other western countries with respect to the terrible abuses that

occurred throughout the economy, the business sector and the governments

suggest that the Asian are small town thieves when it comes to

plundering companies and ripping off shareholders.

During the Asian financial crisis, the U.S. was viewed by many

as a "global economic locomotive" that needed to maintain

its performance until Asia and/or Europe could regain its economic

footing. Now the U.S. engine appears to have run out of steam

and Europe or Japan do not seem ready to take on the load. Can

the world regain positive momentum without a locomotive and what

are the ramifications of continuing weakness in the U.S., Europe

and Japan?

We have to distinguish between markets in terms of dollar sales

and in terms of units. Today, many physical markets are already

larger in China than in the US. I am thinking of steel, where

the Chinese production is larger than the one of the US and Japan

combined, with China still importing steel. Also the markets for

refrigerators, TVs Radios, motorcycles, cellular phones are larger

in China than in the US. Now add the markets of India, Japan,

Indonesia, etc to the Chinese market and you actually see that

Asia by itself is a huge economy in terms of units. I am a believer

in a secular economic military and political decline of the US

and a rise of China and other Asian countries. I think the US

is today where the UK was at the beginning of the 20th century

and that global growth in future will be driven by Asia.

For hundreds of years arguments have been made as to the

potential of emerging markets and the potential they offer. What

we have seen, however, is higher volatility and what you have

termed "gloom boom doom" than one generally finds in

more mature markets, especially over the long term. Would it then

be fair to say that investing in emerging markets is more cyclically-oriented

and a trading opportunity than a long term investment? What should

investors who lack the resources of large institutions and ability

to buy foreign listed securities watch out for?

I think this is a good point. However, I suppose that in many

countries such as China and Russia, there will also be long-term

opportunities. I am not sure that these companies already exist,

but it is clear to me that China will also one day have a GE,

an IBM, MMM, Coca Cola, etc. It is important to understand that

rapidly growing economies have wild business fluctuations. In

my book “Tomorrow’s Gold” I describe the life

cycle of emerging economies and for an investor it is obviously

important to time his purchases well. I may add that I include

in “emerging markets” also “emerging economies”

such as the Internet, the PC, and cellular phones. People who

bought stocks in the TMT sector at the wrong time will probably

never see their money back, as new players will displace the early

leaders of these industries.

One

is continually hearing now about the danger of deflation yet gold,

oil and many other commodities are at, or approaching multi-year

highs. Can you explain this phenomenon and its implications for

investors? Are we beginning to see both forces exist simultaneously

in a manner last seen during the "stagflation" years

of the Carter administration?

Very few people understand the phenomena of inflation and deflation

– both of which can occur at the same time. We have in many

industries over-capacities and the opening of China and so many

other countries is putting terrific pressure on the prices of

manufactured goods. At the same time, these new countries will

have a strong demand for commodities –especially oil and

food products. Therefore, although prices of manufactured goods

could continue to decline, prices of commodities may rise much

further. In addition with Mr. Greenspan not hesitating to print

money and expand credit and the prospect of Mr. Bernanke becoming

Fed Chairman, and the possibility of a War, you have a favorable

environment for commodities.

Technology and the Internet have had tremendous implications

on our lifestyle and the way business is conducted around the

world. After several bad years we are beginning to see investor

interest in smaller Asian Internet companies such as SINA, PCNTF,

REDF, SIFY, etc. and other such as IGLD in Israel. Is this a meaningful

trend and what are your thoughts on technology in general?

Yes,

I think that out of the ruins there will be some winners. I just

don’t know which ones will really make a lot of money.

The Dollar has been weakening and most U.S. investors

are unaware that even investments that have broken even are down

double digits when measured against the Euro and many other currencies.

Do you think this trend will continue and what are the trends

that will arise as a result? Which currencies other than the Euro

will be beneficiaries of this trend?

The

dollar has been far too high considering the economic fundamentals

of the US and considering the policies of its economic decision

makers who don’t care at all about “sound money”.

Therefore, I believe that the dollar has entered again a secular

bear market, whereby it will lose in due course once again 90%

of its value. The question, however, is against what the US dollar

will lose value. Probably it will still decline against the Euro,

as European fundamentals will improve with the inclusion of so

many new countries into Euroland. However, I think the real weakness

will occur against a basket of commodities and against hard assets. The

dollar has been far too high considering the economic fundamentals

of the US and considering the policies of its economic decision

makers who don’t care at all about “sound money”.

Therefore, I believe that the dollar has entered again a secular

bear market, whereby it will lose in due course once again 90%

of its value. The question, however, is against what the US dollar

will lose value. Probably it will still decline against the Euro,

as European fundamentals will improve with the inclusion of so

many new countries into Euroland. However, I think the real weakness

will occur against a basket of commodities and against hard assets.

Many of our readers represent corporations and governments

in Asia and other markets that are seeking to position themselves

to appeal to the international financial community. Do you have

any thoughts or words of wisdom on steps they might take to make

themselves more attractive in this regard?

The best way to get exposure to investors is to perform well and

not to constantly lie to the investment community. Companies should

spend more time running their businesses than talking to investors,

while the executives would do better to read once a while something

else than Newsweek and spend their time on the golf course.

For over a decade there has been a lot of talk about globalization

and the integration of world financial markets. While this has

perhaps slowed down in recent years, we are seeing increased after

hours trading and firms seeking dual listings or even bypassing

their national markets to list on foreign exchanges that they

believe will deliver more attractive valuations. Can you comment

on these developments and their implications for investors and

public corporations?

We are moving towards a global market place where financial assets

will be traded 24 hours a day. With this development it is clear

that some shares will be more actively traded during European

or NY hours than in Asia. After all, whereas the physical markets

in Asia are huge, the financial markets are disproportionately

large in the US compared to real economic activity. Thus, the

high trading volume in the US compared to other countries.

The events of 9/11 have had a dramatic effect on corporate

and political behavior. What are your thoughts on the implications

of the "global war on terrorism"?

I am not so sure this statement is correct. 9/11 has given companies

an excuse for poor performance and to cut travel and entertainment

budgets. It has also given every dumb and totally uninterested

expatriate wife, whose life consists of patronizing the local

American Club, to force the husband to move back to the US for

fear that he might find “something” more attractive

in a foreign country.

Even before 9/11 we began to see a more vocal backlash against

globalization, as seen in the disruption of the Seattle WTO meeting

and the IMF/World Bank deciding to reschedule and scale down their

annual meetings. Now we are beginning to see large-scale demonstrations

around the world against U.S. policy toward Iraq and other international

initiatives, which in many ways are similar to those we last saw

during the Vietnam-war era. Do you think these are related and

can you comment on this trend?

In the sixties, there was the saying about the “ugly American”

because the world was afraid that America would take over the

world economically. Now, we have anti American sentiment for the

US arrogance and lack of sensitivity towards other views and customs.

I admire in many ways the American way of life, but unfortunately

American leaders know and understand what is going on in the world

no better than my four Rottweiler dogs. Moreover, whereas my dogs

only have one standard – to eat – the US has many

different standards depending on their economic interests.

One economy that continues to defy gravity is China, and there

seems to be a growing anxiety all over the world about its continuing

strong growth and the displacement it is causing, particularly

in the manufacturing sector. Can you talk a little about China,

the role it will play in the world economy and what it means for

investors, the U.S. and other countries in the region.

China today, is where the US was in the second half of the 19th

century. At the time it became extremely competitive on world

markets and its entry into the global economy led to a significant

price fall between 1873 and 1900. The opening of China will depress

prices for manufactured goods for a long time. At the same time

China will become Asia’s largest customer for commodities

and its tourists will be the largest group.

Similarly,

Businessweek recently wrote an article comparing the movement

of manufacturing jobs from the U.S. in the 1970-80s to a current

displacement among service workers today. Given the improved communication

and infrastructure that allows one to base an operation almost

anywhere in the world, how will higher-wage and cost economies

sustain their competitive advantage?

I don’t see how in the long run the US and Europe will be

able to compete with tradable services from Asia. India will dominate

the software industry and China the way China will dominate manufacturing.

Research labs will also move to Asia as we have an endless supply

of highly qualified and motivated people who can innovate and

invent.

I notice you are more positive on Southeast Asian countries

such as Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines as opposed to

markets such as Korea, Taiwan and Japan which possess superior

infrastructure, more educated workforces, higher percapita consumption

and a greater corporate and technological base. Can you tell us

why this is the case?

I think that Korea, Taiwan and Japan will suffer to some extend

from the competition of China. The resource based Asian economies

will on the other hand benefit from the rise of China. This does

not mean that stocks in Korea, Taiwan and Japan will not perform

well, as companies can shift their production to China and, therefore,

cut their costs.

What are your thoughts on Japan? What do you make of the

debate between promoting inflation and demand vs. structural reform

and industrial revitalization? Do you think we are at or near

the bottom? Finally, do you think the best opportunities are with

the export-oriented success stories such as Toyota or Hitachi

or more the domestically-focused and/or distressed companies that

will benefit from an economic turnaround?

I believe that in 2003, the Japanese stock market will bottom

out and that good opportunities will arise. I am negative about

Japanese bonds because I see a weaker Yen ahead and also the aggressive

monetizing of the debt is likely to lead to higher inflation and

interest rates.

Korea is viewed as one of the great "post IMF crisis"

success stories. The country has shown a rapid willingness to

reform and investor interest has grown to the point that companies

such as Samsung now enjoy a larger market capitalization than

Sony. It has also a rapid adapter of new technologies and leader

in areas such as online trading, broadband and mobile telephony.

At the same time, consumer debt is rising, unemployment is beginning

to increase and troubles with the North are becoming a growing

international concern. What are your views on Korea and it s economic

prospects?

I think Korea will do just ok. I am not such a great believer

in the success story of the last few years, which was built on

excessive consumer debt. The stock market is somewhat over-sold

and could rally from the present level by 20% to 30% this year.

Any thoughts on the emerging markets of Latin America, Central

and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States and Africa

you can leave with us?

I like some Latin American countries, because they are resource

rich and will benefit in the environment I outlined. The price

level of Argentina and Brazil is low and stocks may actually surprise

on the up-side.

You recently authored a book named "Tomorrow's Gold"

that has been attracting a lot of attention. Can you tell us about

it?

Yes, it is doing very well and it will be translated into several

foreign languages. Many people have written to me that the book

is one of the most readable and interesting investment books.

In my introduction to the book, I wrote that I owe all my knowledge

to people from whom I learned a lot including Henry Kaufman. Sydney

Homer, Charles Kindleberger, and all the classical and Austrian

economists. I also learned a lot from Alan Greenspan, so if I

am one day the head of the Zimbabwe Central Bank, I won’t

repeat the same mistakes….

Thank you, Marc for a most informative discussion. Do you have

any closing remarks for our readers.

"Follow the course opposite to custom and you will almost

always do well"

J.J. Rousseau.

Click

here to purchase "Tomorrow's Gold" directly from Amazon.com

Korea

Needs to Address the Growing Uncertainty of International Investors

By

Keith W. Rabin

Many analysts predicted a

weakening Korean economy last year in the face of an emerging

China, a slow growing Japan and continuing market turmoil in the

United States. To the contrary, a revitalized Korea exhibited

a strong performance. It attracted substantial investor interest

-- and the Korean stock market registered one of the world’s

strongest performances during the first six months of 2002.

This achievement began to erode, however, during the latter half

of the year and has accelerated in recent months. The simple truth

is that Korea -- no matter how competitive its economy, and how

rapidly it implements reforms and expands its corporate capabilities

-- is not large enough to act as an engine of world growth by

itself.

In a nation seeking to establish itself as the "Dynamic Hub

of Asia", the perceptions of foreign investors and business

executives matter more than ever before. Without them, Korea cannot

attract the physical, human and financial resources needed to

position itself as a global technology and financial center or

to enable its companies to develop the value-added strategies

that are essential to maintaining the rapid development Korea

has exhibited in the past.

Rising tensions in the North, increased media focus on Anti-Americanism,

burgeoning consumer debt and this week's downgrade of Moody's

outlook for Korea's sovereign credit rating all contribute to

a growing discomfort among international investors and executives.

Their uneasiness is compounded by the recent election of Korean

President Roh Moo-hyun, who ran on a populist platform and is

largely unknown -- not only outside of Korea -- but also among

many Korean business leaders. The world therefore nervously watches

to see whether Korea will continue to deserve its hard-earned

reputation as the Asian country most eager to embrace reform after

the IMF crisis and as a result offered some of the world's most

attractive investment and business opportunities.

While Koreans tend to hunker down and turn inward when faced with

adversity that is precisely the opposite of what is necessary

at the present moment. Korean business and government leaders

– if they are to maintain the good will and positive perception

they been gained in recent years – must reach out and confront

the problems they are facing. Investors are not seeking to punish

Korea or to retreat from the peninsula. Like everyone else they

are simply seeking the reassurances they need to justify their

decisions.

For example, rising tensions in the North lead Moody's this week

to change its outlook for Korea's sovereign credit rating from

positive to negative. Their belief is based on the assumption

that increased provocation by the North, which has resulted in

an open resumption of its nuclear effort, heightens South Korea's

security risk and the possibility of a military response from

the United States.

This development surprised many investors and business and government

leaders. It has raised their anxiety level, particularly after

several months of media coverage depicting a growing "Anti-Americanism"in

Korea. Several U.S. government leaders have even gone so far as

to question whether it is wise to maintain American security forces

in the nation. One might rightly ask if Moody's actions and the

resulting uncertainty it created were a key factor leading to

an intra-day decline of over 6% earlier this week off the five

day KOPSI index average and whether this is a portent of things

to come.

The answer largely depends on the actions of Korea's new government

and its corporate community. The U.S. until recently was perceived

as a safe haven and in many ways a beneficiary of global turmoil.

This has been changing due to U.S. economic and corporate excesses

as well as the loss of innocence following the 9/11 tragedy. As

a result, international investors and executives, who have been

enduring dramatic losses in dollar denominated assets, have by

necessity begun to regain their appreciation for greater international

diversification.

This theoretically creates a great opportunity for Korea-related

projects and Korean companies who can position themselves as globally

attractive investment opportunities -- yet it will not happen

by itself. Rather than reach inward, Korea-related entities must

reach out and explain current dynamics from their own perspective

in a way that makes sense and which increases their attractiveness

to the international investment community.

Korean opinion leaders need to emphasize while recent actions

by the North are certainly important and need to be addressed,

they do not represent a fundamental change from the security dynamics

of the past fifty years. They might also point out the low historical

correlation between economic growth in South Korea and changes

in South-North relations. Furthermore, the rise in what is seen

as Anti-American sentiment in the South might be interpreted more

as the inevitable result of a young, maturing, empowered, growing

democratic economy. Korea’s rising stature and educated

workforce is giving rise to a truly dynamic human resource pool.

It is seeking greater self expression – not only in its

delivery of cutting edge products, technologies, corporate structures

and a growing range of cultural exports – but also as a

nation that seeks to independently determine its national destiny.

It is also worth noting that Korea represents an increasingly

attractive consumer market in an of itself. This has helped to

give additional depth and strength to its economy. While representing

a highly positive and important trend over the long term, Korean

leaders need to acknowledge investor concern over the rapid rise

of consumer debt. Foreign media reports highlight alarming statistics

such as the record 7% rise in the average credit card default

ratio during the third quarter of 2002. Steps that the Financial

Supervisory Service has taken to curb defaults, including the

imposition of limits on cash advances and higher reserve ratios

on lending institutions receive far less attention and need to

be emphasized.

To maintain Korea’s continuing integration as a vital link

in the global chain of commerce and finance, efforts must be made

to communicate both the evolving growth of the Korean nation as

well as the workings of individual entities on the firm level.

By providing well thought out reasons why foreign investors and

business partners would be wise -- not only to maintain -- but

to expand their involvement with Korean enterprises; in addition

to explaining the factors that drive their behavior, investors

will be far more likely to understand that volatility moves in

both directions.

This will help to lead them to the conclusion that current tensions

with the North and other economic problems in the face of a global

slowdown are only temporary interruptions in the long-term growth

pattern that Korea has consistently exhibited for over half a

century. Therefore, they will come to understand that any present

trend downward, which may continue in the current incendiary environment,

represents nothing more than a long term buying opportunity.

Interview

on Japanese M&A Environment with Mr. Kiyoshi Goto, Director-General,

Department of Business Development, Development Bank of Japan

By

Keith

W. Rabin

Mr.

Kiyoshi Goto joined the Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) in 1978.

His overseas experience and successful assignments in internationally

related work are extensive, totaling fifteen of his 25-year experience

at DBJ. He received his MBA from the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth

College in 1984. In 1987 he was dispatched to the International

Energy Agency in Paris, the energy forum of the OECD, and worked

as an energy economics analyst for three years. From 1995 to 1997

he was in DBJ’s International Department, in charge of extending

loans to foreign companies investing in Japan. Then Mr. Goto was

named Chief Representative of DBJ's Washington D.C. office, where

he worked hard to provide a better understanding of DBJ's activities

as well as the Japanese economy and society through thirty plus

presentations and lectures in three years. Last April he was given

a new mission, to lead a team providing M&A advisory service,

a new business for DBJ. Mr.

Kiyoshi Goto joined the Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) in 1978.

His overseas experience and successful assignments in internationally

related work are extensive, totaling fifteen of his 25-year experience

at DBJ. He received his MBA from the Amos Tuck School at Dartmouth

College in 1984. In 1987 he was dispatched to the International

Energy Agency in Paris, the energy forum of the OECD, and worked

as an energy economics analyst for three years. From 1995 to 1997

he was in DBJ’s International Department, in charge of extending

loans to foreign companies investing in Japan. Then Mr. Goto was

named Chief Representative of DBJ's Washington D.C. office, where

he worked hard to provide a better understanding of DBJ's activities

as well as the Japanese economy and society through thirty plus

presentations and lectures in three years. Last April he was given

a new mission, to lead a team providing M&A advisory service,

a new business for DBJ.

Hello Goto-san, it is a pleasure to speak with you again. Can

you tell our readers something about the Development Bank of Japan,

its role and mission, as well as your own background and activities

there?

The Development Bank of Japan (DBJ) is a governmental financial

institution established in 1951. DBJ's mission is to contribute

to the development of the Japanese economy and society via the

provision of “quality” financial services that usually

cannot be accommodated by private financial institutions. DBJ's

contribution to Japan's wealth, I believe, has been widely acclaimed.

Since readers of this newsletter mostly work outside Japan, I

should emphasize that DBJ has made strenuous efforts to assist

foreign firms wanting to enter the Japanese market. In 1984, DBJ

crafted loan programs specifically designed for foreign companies

investing in Japan, and those programs have been well received.

In fact, the 1996 Economic Report of the President noted our efforts

in this area. I have never heard of any Japanese institution other

than DBJ being named in the Report.

I have devoted more than half of my career at DBJ to international-related

business. After having assisted foreign companies for two years

through the loan programs I mentioned, I went to Washington, D.C.

and worked as a public relations officer for DBJ—and even

for the Government of Japan—giving talks on a wide variety

of issues including DBJ's loan programs and the state of the Japanese

economy. You may recall that in the Business Opportunities in

Japan symposium organized by the Japan External Trade Organization

(JETRO) in November 1997, I gave a presentation titled, “Investing

in Japan: A New Trend”, which pointed out the growing importance

of M&A in Japan. Last April I was assigned to lead the newly

established department in charge of M&A advisory services.

The

development of M&A deals is a new area for DBJ. Can you tell

us why DBJ is moving in this direction and how the "culture"

of the institution is changing as you move to initiate this type

of activity? The

development of M&A deals is a new area for DBJ. Can you tell

us why DBJ is moving in this direction and how the "culture"

of the institution is changing as you move to initiate this type

of activity?

Yes, we are a Johnny-come-lately in this field. But we already

realized how important M&A was for the Japanese economy a

decade ago and carefully studied how DBJ, as a policy-implementing

body, could supplement the market. We started this new service

mainly for two reasons. First, M&A, once regarded in Japan

as a malicious business conduct, is gradually becoming accepted

as a useful business tool, but some distaste for M&A remains.

We thought that an advisor whose mindset differed from that of

private advisors was needed in order for M&A to become rooted

in Japan, that is, an advisor who seeks a triple equilibrium.

You may have heard talk of “win-win” deals, deals

in which both the sellers and the buyers get fair shares of the

value from the transactions. That, however, is easier said than

done. The reality is that one side usually wins more than the

other, sometimes unjustly. Being a governmental institution, we

thought we should aim to assure that nobody goes overboard in

an M&A transaction, and we do this by taking into account

not only the benefits to the sellers and to the buyers, but also

to the economy as a whole. I call this the “triple-win”

approach. The second reason we started an M&A advisory service

is that even though M&A has gradually become a business tool

in Japan, only blue-chip companies have had the luxury to use

it. Many small-to-medium-sized firms are ignored in this market

because the deal size cannot generally justify the costs for professional

services. We thought that we should give a helping hand to such

companies to support the healthy development of the M&A market.

Thus, we decided to jump into this new area.

This movement, adding M&A advisory services to DBJ's menu,

meets the diversifying needs of corporate clients and increases

the value of DBJ's financial services. This move also has a positive

impact internally at DBJ in the sense that a solution-oriented

approach is setting in; we should provide not only funds but also

knowledge. Also this service offers DBJ a new avenue to a fee-based

business.

Can you give us some specific examples of M&A deals you

have completed or been working on and the type of deals you are

targeting in the future?

Because we are a latecomer in this field, we do not yet have many

completed deals to prove the effectiveness of DBJ's “triple-win”

approach to M&A advisory services. However, a deal we completed

last November may illustrate DBJ's approach. We served as an advisor

for Meidensha Corporation, a heavy electric machinery manufacturer,

on a deal between its affiliate, Meiden Hoist System, and KCI

Konecranes, a world leader in the crane market. Meiden Hoist System

had been struggling in the depressed and over-crowded market,

and KCI Konecranes, though long aspiring to enter Japan, had not

found a suitable arrangement. This strategic alliance not only

benefited Meidensha and KCI Konecranes, both of whom received

a fair share of the value, but also achieved national policy objectives,

namely, business restructuring and promotion of foreign direct

investment, thus significantly contributing to the Japanese economy.

KCI Konecranes included DBJ's name in its press release on this

alliance, which, I believe, is quite remarkable since an advisor

is not usually mentioned in this kind of release and furthermore

we served as an advisor for Meidensha -- not for KCI Konecranes.

This deal clearly demonstrates that our aim is truly for “win-win”

transactions. Perhaps one might wonder if KCI’s praise was

earned at Meidensha’s expense—that is, some might

think that Meidensha was underrepresented and the notion of triple

equilibrium is a joke. One thing is evident: Meidensha could have

terminated the contract with us anytime they wanted and would

have done so if they had not been satisfied with our services.

Let

me tell you how I understand M&A. M&A is an economic transaction

that really does create value that did not formerly exist. The

seller provides a platform for value creation and the buyer offers

managerial, technical and other expertise. Unless the buyer and

seller get fair shares of value created, the deal won’t

close and nobody will gain. Yes, an advisor works for a client,

either the buyer or the seller, and gets fees. However, if you

regard M&A as a game of win or lose, you are quite likely

to lose fees you could otherwise have earned. The fact that more

than half of M&A deals end up as failures, according to various

surveys and studies, may back up my notion. We at DBJ have a mindset

to make a project as feasible as possible in the long run, which

we have done through our financings since the bank’s establishment.

As part of our implementing policy, we have to make sure that

the projects we finance will have positive impacts on the Japanese

economy and society. This approach is also the backbone of our

M&A activities. On the other hand, take an example whereby

a client comes to us and says that it is looking for an M&A

opportunity simply to boost its earnings per share by acquiring

a company with a low price-earnings ratio. We do not provide advisory

service for such clients. I hope this will help explain our M&A

advisory policy. We are targeting deals that will contribute to

corporate/business restructuring, revitalization of local economies,

and promotion of foreign direct investment. Let

me tell you how I understand M&A. M&A is an economic transaction

that really does create value that did not formerly exist. The

seller provides a platform for value creation and the buyer offers

managerial, technical and other expertise. Unless the buyer and

seller get fair shares of value created, the deal won’t

close and nobody will gain. Yes, an advisor works for a client,

either the buyer or the seller, and gets fees. However, if you

regard M&A as a game of win or lose, you are quite likely

to lose fees you could otherwise have earned. The fact that more

than half of M&A deals end up as failures, according to various

surveys and studies, may back up my notion. We at DBJ have a mindset

to make a project as feasible as possible in the long run, which

we have done through our financings since the bank’s establishment.

As part of our implementing policy, we have to make sure that

the projects we finance will have positive impacts on the Japanese

economy and society. This approach is also the backbone of our

M&A activities. On the other hand, take an example whereby

a client comes to us and says that it is looking for an M&A

opportunity simply to boost its earnings per share by acquiring

a company with a low price-earnings ratio. We do not provide advisory

service for such clients. I hope this will help explain our M&A

advisory policy. We are targeting deals that will contribute to

corporate/business restructuring, revitalization of local economies,

and promotion of foreign direct investment.

Substantial wealth has been created in the U.S. by investor

groups who assume possession of distressed or underperforming

assets and then move to reduce costs and introduce other "re-engineering"

techniques to restore profitability. One might imagine there are

many opportunities of this kind in Japan given the depressed economic

environment it has experienced over the past decade, yet we have

yet to see this become a defining trend. Can you give us some

of the reasons why and whether this might change in the future?

Additionally, what is the likelihood that virtually bankrupt corporates

or financial institutions will be allowed to fail?

An active market for distressed assets in Japan cannot be created

overnight. But one is developing. Evidence is that the number

of MBOs increased significantly in Japan, from thirteen transactions

in 2000 to forty-two in 2002. Recently, UK-based 3i withdrew from

the market. However, major foreign funds are still in Japan and

Japanese players are becoming active in the distressed-asset market.

Unison Capital, Advantage Partners and MKS Partners have been

quite visible. DBJ also plays an important role in this regard.

DBJ put equity into Nippon Mirai Capital, a new entrant in this

field and we have been investors in several corporate restructuring

and turnaround funds. Our loan function also supports the activities

of turnaround private equity. For example, Unison Capital made

equity investment in ASCII, a publisher of PC-related magazines

and books, which had been in serious trouble for so many years

despite twice changing management. DBJ appreciated Unison’s

turnaround scheme and, together with other commercial banks, provided

funds necessary for its smooth turnaround. ASCII made a surprisingly

speedy and dramatic comeback. In Japan I expect those “hands-on”

style investors—in your words, those introducing “re-engineering”

techniques—to be the key for Japan’s recovery.

About the George Romero question, by that I mean the question

about “zombie” companies, I would like to respond

with a quote from Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species:

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor

the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the

most adaptable to change.” This is the philosophy behind

Unison Capital, which I heard from its founder, Ehara-san. According

to Darwin’s law, the answer is crystal clear.

With

the Nikkei at twenty year lows, many investors have been ignoring

Japan in favor of China and other Asian markets that they believe

offer more dramatic growth and potential. Can you tell us why

they should devote more attention to Japan and about some of the

opportunities they may be missing?

China is regarded as the country of the future by many. China’s

entry into the WTO indicates that an immense market is finally

opening. But I think there is still a rocky road ahead. Risks

in China’s financial sector alone could ruin the economic

potential. Since the stakes for prosperity coming from China are

so huge, every multilateral and bilateral effort should be made

to ensure her healthy growth. Still you should keep in mind that

your love for China might sometimes blind you to her faults. Talking

about Japan, it is, no doubt, saddled with numerous problems.

However, according to World Economic Forum's Global Competitiveness

Report 2002, Japan's position improved considerably, from 21st

in 2001 to 13th in 2002. Technology represents the key driver

for this improvement. The report points out that the country’s

innovative power has remained very strong, which compensates for

drops in the macroeconomic index and public institutions index.

This implies that once the macroeconomic situation improves and

the governance problems can be addressed properly, which admittedly

are not easy tasks, “the sun should also rise.” Investors

should follow Japan carefully, that’s for sure; I see no

reason to ignore Japan.

Many analysts view the primary economic problem in Japan

as being the need to deal with non-performing loans, and they

maintain that little can be done until this problem is addressed

in a definitive manner. Furthermore there is also a common perception

that there is little or no demand for commercial loans among borrowers.

Do you share the view that no progress can be achieved in Japan

without resolving the NPL issue? Furthermore do you believe that

there is little or no demand for new commercial loans?

Oh, boy! This has been extensively discussed among high-profile

economists and I may not be the right person to answer this. My

opinion is that the NPL problem should be properly addressed.

However, I think we should distinguish between two types of NPLs:

NPLs stemming from the burst of the bubble and NPLs stemming from

the deepening deflation. The former had long been left disregarded

partly because banks thought they could be disposed anytime as

unrealized gains on securities but most of them have been written

off. The latter is a new pile of bad loans springing up like mushrooms

due to worsening deflation. Since the problem we now face is the

latter, what is most needed, I think, is comprehensive counter-deflationary

measures. I will leave what the measures should be to policy-makers

and economists, though. A lot should be done to address the NPL

problem properly.

Regarding the demand for commercial loans, if you look at some

macro statistics on liquidity or free cash flow of non-financial

firms, you see that in aggregate firms have excess cash. Demand

for commercial bank loans has been weak because of the slack economy.

Banks themselves have changed their lending policies, leaning

toward charging premiums applicable to the risks involved, which

I think is the right direction. These two factors have caused

the decrease in commercial bank loans.

When

talking about direct investment in Japan, much of the emphasis

has been on greenfield rather than M&A projects. Part of the

problem has been the dichotomy between, one, domestic constituencies

and management who want to maximize valuations and/or are resistant

to change and, two, foreign investors who seek to introduce efficiencies

and achieve maximum gain. This adversarial relationship is standard

practice in the U.S., but is often perceived to cause excessive

tension in a consensus-driven Japan. Is it simply a matter of

time before Japan takes more fully to U.S.-style M&A as a

corporate finance tool?

I do not fully share your view. First, even the Japanese government

(the Japan Investment Council headed by the prime minister) a

long time ago realized the importance of promoting foreign direct

investment via M&A and in 1996 made an official statement

“On the Preparation of an M&A Environment in Japan.”

It was so epoch-making that the media bashed it, claiming the

government was selling off Japanese firms. Secondly, although

Japanese have been highly allergic to M&As because of negative

aspects such as greenmailers and hostile takeovers in the U.S.

in the 1980's, their attitude has been changing. Carlos Ghosn

of the French company Renault successfully revived Nissan Motor

and French coach Philippe Troussier energized the Japanese soccer

team. Is Mr. Ghosn still a public enemy in Japan? Definitely,

not. We all know that we need foreign management know-how to rejuvenate

the Japanese economy. When I was studying at Amos Tuck in 1982–1984,

the U.S. was eager to learn from Japan, and you guys did it right.

You benchmarked Japan and adjusted the Japanese model to meet

the U.S. context. It’s our turn, isn’t it? M&A

has become recognized in Japan as a common corporate finance tool;

there is no doubt about it. Looking from North America, it may

seem a snail's pace. But our team has been working hard to assist

Japanese firms to benefit from M&A, especially cross-border

M&A, and hope to change that perception.

In the U.S., many business owners and entrepreneurs look

to sell all or part of their companies for the right price, even

when they are doing well, for either strategic reasons or to realize

some of the underlying equity, and these transactions when properly

executed are perceived as positive achievements. In Japan, however,

they are often viewed as failure. For that reason, it has been

rare to see healthy Japanese firms turn to M&A as a means

to realize value or to enhance their competitiveness. Do you think

this is a fair statement, and, if so, what can be done to change

this perception in Japan?

Well,

since corporate/business restructuring has been the single most

important issue in Corporate Japan recently and M&A has been

used as a restructuring tool, you might have such an impression.

But Japanese blue-chip companies have become focused on corporate

value creation and have used M&A to increase the value-based

metric, best known as “economic profit” or “economic

value added.” In short, we are too busy restructuring. But

you should note that restructuring also increases corporate value

and that, usually, the more ambitious the restructuring the more

the growth. You may have in mind something like Jack Welch's 1987

swap of GE's consumer electronics business for the medical systems

interests of Thomson of France. If that's the case, I admit it

may take a decade for Japanese to see such a deal. But didn’t

the GE-Thomson deal frighten even the U.S. people to death?

Even though one can make a good argument as to why Japan

offers an attractive investment opportunity, many companies and

investors we deal with find it extremely difficult to identify

attractive companies that possess a sufficient understanding and

appreciation of the investment process -- despite a professed

desire to attract foreign investment. Furthermore, business practices

and sensibilities can be very different. As an ivy-league MBA

graduate, can you give any advice to foreign investors on how

they might identify specific investment opportunities in Japan

and not only go about facilitating transactions but also to maintain

good relations with their Japanese counterparts after they are

consummated?

To expedite successful M&A in Japan, I would advise them to

choose an advisor who has expertise in cross-border transactions

as well as a good understanding of Japanese corporate culture.

Marriage between two different parts of the world can never be

easy and there are a lot of difficulties to overcome. An advisor

who is well-versed in cultural differences could successfully

build a bridge between the two. Our team has strong competence

in cross-border deals since DBJ has for almost twenty years accumulated

vast know-how in cross-border transactions through its financial

assistance to foreign firms entering the Japanese market. The

Meidensha–KCI Konecranes deal I introduced earlier demonstrates

our capabilities.

Part

of the problem in initiating M&A deals is the complexity of,

and large amount of time that must be devoted to, individual transactions.

Many people point to the scarcity of qualified service professionals

in Japan, even in large-scale transactions. This can be even more

problematic within the smaller scale transactions you are focusing

on as they lack the scale needed to amortize the costs needed

to allow successful closure. Can you comment on this problem and

how if might be addressed?

Japan’s M&A market is very young, relative to that in

the U.S., and an overemphasis on lending activities by Japanese

banks accounts for the lack of qualified M&A advisors here.

However, competence in this business is quite different from the

one in the derivatives house. You do not have to know the Black

and Scholes model to be a good advisor. The weapons you should

have are basic tools in valuation and some of the buzzwords in

this world. What makes you an excellent advisor are an analytical

capability to formulate corporate strategy and communication skills,

which can be cultivated through work experience. Therefore, Japanese

advisors could sooner or later be parallel to their U.S. counterparts.

Regarding the cost recovery issue in smaller deals, a clear-cut

answer cannot be expected. The amount of work required for an

M&A transaction, unfortunately, hardly changes with deal size.

Therefore, an institution like us should contribute for the time

being, subsidizing smaller deals. Since DBJ alone cannot support

smaller M&A deals, a more comprehensive approach should be

devised: by giving technical assistance to the M&A sections

of local banks, for example.

When

foreign investors talk about investing in Japan, they are largely

talking about Tokyo and perhaps Osaka. Can you talk a little about

other geographic areas of Japan and the potential that they offer? When

foreign investors talk about investing in Japan, they are largely

talking about Tokyo and perhaps Osaka. Can you talk a little about

other geographic areas of Japan and the potential that they offer?

Yes, the only city in Japan that many foreign investors can name

may be Tokyo—outside of, perhaps, Osaka, because of its

international airport and Universal Studios Japan—so, it’s

no wonder that most foreign direct investment and M&A has

focused there. However, this should not be construed to mean there

is a lack of opportunities in other parts of Japan. It is just

difficult for foreign investors to find the hidden jewels in areas

other than Tokyo. I can name some of the areas which may appeal

to foreign investors: Sapporo City in Hokkaido, where high technology

companies cluster together; the northern Kyushu area, as a gateway

to East Asian countries; and the Nagano area, where Japan’s

manufacturing prowess can be found. As for how to mine these mother

lodes, DBJ can assist in many ways. As I mentioned, DBJ has assisted

foreign companies investing in Japan for more than twenty years

using our network all around Japan: our branch offices, local

governments and other related institutions, such as JETRO and

the Japan Industrial Location Center. In terms of M&A, we

have a network with forty local banks and regularly exchange information.

We think it would be prudent for your readers to keep us in mind.

Thank you Goto-san for sharing your thoughts with our readers.

Do you have any closing thoughts or comments you would like to

leave with us?

Let me close by borrowing from the final scene of the 1985 movie

Rambo: First Blood II:

"Kiyoshi, non-performing loans, deflation, everything that

happened here may have been wrong. But, damn it, Kiyoshi, you

can't hate your country for it."

"Hate? I'll die for it."

Yes, our team will serve the country via M&A to the death.

CAN ANYONE TELL US WHY JAPAN'S TECH ECONOMY IS BROKEN? Is Japan's high-tech economy broken? We don't think so. Derailed perhaps. But if you understand the mechanics, you can gain access to amazing opportunities for business and technology in Japan. Nobody else knows Japan like we do. Find out what's going on, direct from Tokyo, weekly and free. Four great newsletters at http://www.japaninc.com.

Investing

in Japan via Tax Efficient Silent Partnerships

By

Andrew H. Thorson

Partner, Dorsey & Whitney LLP (Tokyo)

Companies investing, acquiring or operating

subsidiaries in Japan should consider using the “silent

partnership” or “TK” (known in Japan as a Commercial

Code tokumei kumiaia) as a tax efficient vehicle for

their transactions. By using the TK vehicle, in certain circumstances

investors can realize substantially reduced Japan-side tax burdens

which would otherwise set up a road block to viable returns

on an investment.

In the typical scenario, the sole-shareholder of a Japanese

company might fund the company solely via additional share purchases.

In such cases, the shareholder could be paying an effective

tax rate of up to 47.8% including combined Japanese local and

national taxes plus the 10% withholding tax on dividends paid

to the U.S. shareholder. What if the shareholder could reduce

the tax burden in Japan to 20%? Depending upon the circumstances,

financing the Japanese company via a TK could result in such

a reduction.

What is a TK? A TK is not a business entity. TKs are

contracts between silent “investors” and business

“operators”. The investor contracts to provide an

asset (cash or other property) for use by the operator in its

business. In exchange, the operator pays the investor an agreed

percentage of the business’s pre-tax profits.

Under the TK contract, the investor receives no ownership right

in the business. The investor receives only a right to profits.

Furthermore, while the TK contract may provide the investor

with certain investigatory and informational rights, the investor

receives no management rights. TK contracts are simple and often

require little more than an agreement upon scope of the subject

business, the allocation of profits and losses, and terms relating

to termination/expiration.

A TK is not a loan agreement or a leasing agreement. However,

the operator deducts payments to the investor on a pre-tax basis.

Usury limitations do not apply on payments of profits to the

investor. This is one advantage of the TK when contrasted to

inter-company loan financing.

Potential Tax Efficiencies. As indicated above, if properly

established and monitored, use of a TK structure for a Japan

investment could reduce the effective Japanese tax rates for

certain Japan investments.

Take the simple example of financing a wholly-owned subsidiary.

When a U.S. investor purchases or establishes a wholly-owned

corporation in Tokyo the effective tax rate on profits can be

estimated at 47.8% (approximate combined corporate tax rate

of 42% plus a 10% withholding on dividends to U.S. companies

under the Japan – United States tax treaty).

If properly structured, the tax burden in Japan could be reduced

to a 20% withholding tax on TK profits paid to the U.S. investor.

TK structures have been used in more complicated structures

as well, for example in aircraft and other asset leasing arrangements

wherein they lawfully reduce tax burdens in Japan.

Freedom of Contract and Limitations on TK Uses. The Commercial

Code of Japan prescribes the fundamental legal foundation of

the TK structure but TK structures are generally subject to

the principle of “freedom of contract”.

The TK structure is, however, not without limitations. An investor

is at risk and does not receive fixed payments as a lender might.

The investor also has no right to payment when the business

has no profits. If the asset is fully consumed by the business,

then the investor receives nothing upon termination or expiration

of the TK.

Furthermore, a silent investor may enjoy certain contractual

rights of investigation and access to information, but participation

in the management of the entrepreneur’s business could

result in the silent investor being treated as an ordinary shareholder

for tax purposes. Such participation could also result in joint

and several liability, or the nullification of the legal validity

of the TK. For this reason, the TK investor should not be a

shareholder of the TK business, but could be an affiliate of

the TK business’s shareholder – and could be an affiliate

domiciled in a tax haven.

Potential scrutiny by Japanese tax authorities is perhaps the

material concern in structuring a TK. Generally speaking, however,

the material concern of tax authorities relates to treaty shopping.

Consider, for example, the case in which US Parent Inc., a U.S.

corporation, establishes an entity, X Inc., in country X where

the tax treaty between country X and Japan provides that TK

profit distributions to companies of X are entirely free from

Japanese taxation. If X Inc. was established for the sole purpose

of taking profits from Japan Sub K.K. via a TK to avoid Japanese

taxes, then this is the type of case wherein Japanese tax authorities

might consider issuing an assessment notice. Under such circumstances,

X Inc. lacks real substance and could be considered a treaty

shopping vehicle established to avoid Japanese taxes otherwise

payable by a U.S. corporation. Some commentators indicate generally

the importance of being able to demonstrate to Japanese tax

authorities a rational basis for entering into a TK before taking

into account associated tax benefits.

Scrutiny of TKs. The TK is a typified form of commercial

code contract, which is used by some well-known Japanese corporations

in various capacities. Use of a TK in and of itself is not generally

considered suspect activity or harmful to the reputation of

an investor.

In recent years the tax authorities have found TKs widely used

in business practice, yet until somewhat recently, aircraft

leasing has been perhaps the only major transaction in which

TKs were regularly utilized. We understand that rumors of a

disallowance of TK tax benefits have been surfacing annually

for several years now, but based upon informal discussions with

officers of related authorities, believe there is no impending

move within the tax authorities to eliminate such benefits.

There have been quasi-governmental study groups formed to research

the current uses of the TK structure in Japan, however, a change

in law to prohibit the use of TKs could be difficult for the

government. Tax authorities are perhaps more likely to crack

down on misuses of the form (such as in treaty shopping) rather

than abolish it.

As discussed above, a TK must be used appropriately. In structuring

a TK for a Japan investment, particular care must be taken to

ensure that the intended benefits are supported by sound commercial

rationale and will achieve the intended benefits. The ultimate

decision of whether or not a TK is suitable for a Japan investment

will rest upon the results of a comprehensive review of all

of the relevant facts and associated tax concerns.

ANCIENT

HISTORY: Thailand and Cambodia make peace – but for how long?

By

Jonathan Hopfner

While the war on Iraq is

in the early stages, another, a less prominent conflict drew to

a close March 22, when checkpoints on the Thai-Cambodia border

were officially reopened after remaining shut for nearly three

months in response to the torching of the Thai embassy in Phnom

Penh.

The Thai-Cambodia dispute registered as little more than a blip

on the global radar, but despite both governments’ insistence

that they consider the matter resolved, could yet have serious

implications for relations between the two countries and the fragile

unity of the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations

(ASEAN).

The conflict was also a potent reminder that in Southeast Asia,

ancient history continues to exert a forceful, if often unnoticed,

influence on present events. The furor was sparked when a Thai

actress popular in both her native country and Cambodia, Suwanan

Khonying, allegedly commented that she would not visit Cambodia

until it returned the 1100 year-old Angkor temple complex to Thailand.

While Khonying insisted she uttered these lines in a role on a

soap opera that aired in Thailand two years ago, her words appeared

in the Khmer press early this year, prompting Cambodian Prime

Minister Hun Sen to comment at a rally in January that Khonying

was “not worth a blade of the grass that surrounds Angkor.”

What happened next stunned even those well accustomed to Cambodia’s

political instability. On January 29, bands of protesters that

had gathered in front of the Thai embassy in Phnom Penh broke

into the compound and set the building alight. Having exhausted

government targets they next turned their attention to the private

sector, burning and looting Thai-owned businesses throughout the

capital. By the time order was restored over 30 firms, including

hotels, restaurants and airline offices, were damaged or destroyed;

Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra had sent five planes to

the capital to evacuate Thai nationals and the Cambodian ambassador

to Bangkok was expelled. Future tallies estimated the riots cost

Thai companies at over 2 billion baht, but it is more difficult

to gauge the fiasco’s effect on the already tenuous relations

between the two nations.

Theories as to the true causes of the incident abound; Thai Ambassador

to Phnom Penh Chatchawed Chartsuwan implied upon his return to

Bangkok that the riots were not spontaneous and that the Cambodian

police were slow to respond to his requests for assistance. Many

observers accused Hun Sen of deliberately whipping up nationalist

sentiment ahead of nationwide elections in July; a time-honored

tactic of Cambodia’s current administration. The Cambodian

government itself accused opposition leader Sam Rainsy of fomenting

disorder to discredit Hun Sen and his party; a charge Rainsy has

hotly denied.

More insightful analysts have suggested that the Cambodian unrest

had been brewing for some time. Thailand and Cambodia have been

trading salvos for years over two other temple complexes on the

Thai-Cambodian border that both countries lay claim to. More of

a factor may have been Cambodians’ increasing resentment

over what they see as Thailand’s economic colonization of

their country; trade along the border reached 18.7 billion baht

(US$420 million) last year, with Thailand recording a surplus

of a whopping 17.76 billion (US$396 million). Much of Cambodia’s

nascent infrastructure, including its mobile phone network, is

wholly or partially owned by Thai firms. Even tourism, which the

Cambodian government has upheld as a key engine to the country’s

development, has grown under Thai auspices; three of the largest

hotels in Phnom Penh are Thai-owned and Bangkok Airways enjoys

a virtual monopoly on the lucrative route from Bangkok to Siem

Reap and the temples of Angkor. Thai music and television is so