|

|

THE

KWR INTERNATIONAL ADVISOR THE

KWR INTERNATIONAL ADVISOR September

2003 Volume 5 Edition 4

In this issue:

|

U.S. Markets and Economy: The Bulls Want To Run, Baby!

By

Scott B. MacDonald

Summer

is over and it is time to go back to work. We think that September

is going to be a good month for the equity and corporate bond

markets. The bulls clearly want to run. Despite the summer meltdown

in U.S. Treasuries, the power blackout and the vacation season,

corporate bond spreads were driven tighter in August by a combination

of good economic news, the possibility that the new bond issue

pipeline could be relatively light due to incrementally higher

borrowing costs and the absence of any major negative geo-political

news. This combination also proved to be a tonic for the stock

market, with the Dow consistently staying above the 9,000 mark

for several months now – and recently even surpassing 9,500.

The NASDAQ has also perked along, reflecting renewed investor

interest in technology. Equally significant, the IPO market is

beginning to show signs of life. According to Bloomberg, IPOs

over the last two months totaled $10 billion, four times the first

quarter of 2003 and higher than the $9.1 billion seen in the second

quarter. We expect these trends to continue through the fall --

possibly into next year. At the same time, we also see a lot of

things that remain problematic and portend tough challenges later

in 2004. Summer

is over and it is time to go back to work. We think that September

is going to be a good month for the equity and corporate bond

markets. The bulls clearly want to run. Despite the summer meltdown

in U.S. Treasuries, the power blackout and the vacation season,

corporate bond spreads were driven tighter in August by a combination

of good economic news, the possibility that the new bond issue

pipeline could be relatively light due to incrementally higher

borrowing costs and the absence of any major negative geo-political

news. This combination also proved to be a tonic for the stock

market, with the Dow consistently staying above the 9,000 mark

for several months now – and recently even surpassing 9,500.

The NASDAQ has also perked along, reflecting renewed investor

interest in technology. Equally significant, the IPO market is

beginning to show signs of life. According to Bloomberg, IPOs

over the last two months totaled $10 billion, four times the first

quarter of 2003 and higher than the $9.1 billion seen in the second

quarter. We expect these trends to continue through the fall --

possibly into next year. At the same time, we also see a lot of

things that remain problematic and portend tough challenges later

in 2004.

First, at least on the surface, the outlook for the U.S. economy

is looking better. Durable goods orders are up; new home sales

reached their second highest level in history during July and

early August; and manufacturing in August expanded at the strongest

pace in eight months. Inventories are also being depleted at a

faster pace than earlier thought. Even global semiconductor sales

are up, rising 10.5% in July, the fifth straight monthly gain.

All of this is reflected in GDP numbers: real GDP for Q2 was revised

from 2.4% to 3.1%, well above consensus. We think real GDP will

be in the 3.6% range for the rest of the year, moving our estimate

of growth from 2.4-2.6% to around 3%. There is something to be

said about pumping liquidity into the system. Even the World Bank

is more bullish, looking to stronger growth next year based on

a revival of world trade, stronger domestic demand in most countries

and an ebbing of international tensions.

In addition to more positive economic data, the geo-political

environment – while remaining fraught with peril – has

not heated up to the point that it is disturbing the fervor of

investors who remain intent on bidding up equities – which

continue to trade at historically high valuations. Yes, terrorist

attacks are occurring in Southeast Asia and the Middle East, and

North Korea remains a challenge. However, negotiations with North

Korea continue, key Islamic radicals were arrested in Southeast

Asia and Saudi Arabia, and some form of Israeli-Palestinian dialogue

continues. We also expect the United Nations will eventually assume

a greater role in Iraq, which could help to stabilize the situation.

From equity and corporate bond market standpoints, the improvement

in economic data and a perceived reduction in international tensions

are sending the signal that the recovery is sustainable.

Nevertheless, while we think that economic growth has room to

run, not everything is positive. For a full-fledged recovery we

still need to see sustainable gains on the employment front. We

take note of a recent statement by the National Association of

Manufacturing that the recovery for U.S. manufacturers is "the

slowest on record since the Federal Reserve began tracking industrial

production back in 1919." Some 2.7 million manufacturing

jobs were lost over the past 36 months. What is needed to reduce

unemployment and stabilize manufacturing employment is a long

awaited and still anemic return of capital spending. If this occurs

during Q3, the recovery could gain further momentum in Q4 and

2004. In addition, the U.S. deficit is heading into record numbers.

While this is not a concern in the short-term, it could have long-term

consequences, especially if measures are not taken to deal with

the situation.

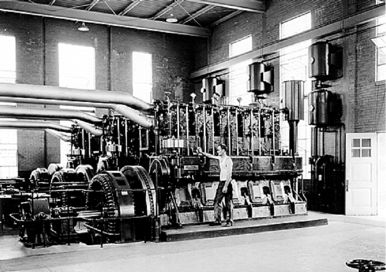

There

is also the issue of the state of U.S. utilities. The August power

outage that hit the United States and Canada was a major shock

to the American public and demonstrated that the North American

utility sector has problems. In fact, the blackout indicated that

the U.S. system of regulating utilities, a mix of feudal-like

local authorities and a less than forceful federal regular, the

FERC, combined with some poor management teams sprinkled across

the country, is dangerously offline. The result was that billions

of dollars of business was lost, either in closed restaurants,

spoiled grocery store goods or powerless factories. Idle factories

do not produce durable goods. It is now estimated that $60-100

billion is needed to upgrade the U.S. utility system. There

is also the issue of the state of U.S. utilities. The August power

outage that hit the United States and Canada was a major shock

to the American public and demonstrated that the North American

utility sector has problems. In fact, the blackout indicated that

the U.S. system of regulating utilities, a mix of feudal-like

local authorities and a less than forceful federal regular, the

FERC, combined with some poor management teams sprinkled across

the country, is dangerously offline. The result was that billions

of dollars of business was lost, either in closed restaurants,

spoiled grocery store goods or powerless factories. Idle factories

do not produce durable goods. It is now estimated that $60-100

billion is needed to upgrade the U.S. utility system.

While everyone agrees the system is in need of repair, consensus

ends when it comes to who should pay and want kind of system is

required. For much of the U.S., utility industry times are hard.

Many of the companies already have large debt loads, are cutting

costs, and selling non-core assets. Rating agencies have been

bearish. While these same companies often purchase energy on deregulated

markets, they sell power at controlled prices (and are unable

to pass on any price increases). Local political establishments

are active in protecting the consumer. Consequently, Washington

has the potential to be a gridlock on utility reform – with

the Democrats declaring that the Republicans are in the pocket

of greedy utility companies and want to pass reform legislation

that will open up federally protected lands to oil and gas exploration.

For their part, the Republicans are grousing that the Democrats

want state intervention and control – basically a socialist

approach to an already troubled industry. To some extent both

sides are right. Therefore, we expect a lot of talk over the utility

industry in the months to come, but real action with big price

tags will be slow. In this case talk is indeed cheap – at

least until the next power outage.

Despite the concerns over unemployment (still in the 6% area),

growing budget deficits, and potential energy problems, the Bush

administration is geared on pushing enough liquidity into the

system to make certain the recovery gets its feet and moves –

at least until the November presidential election. As we have

stated all along, the impact of the federal government pumping

billions of dollars into the economy will stimulate growth. The

trick is to have enough stimuli to allow the consumer an opportunity

to consolidate debt and rebuild savings, which must be balanced

with renewed capital spending. The latter is beginning to happen

very gradually. For the Bush administration the bottom line is

to grow the economy and win re-election. Beyond that policy priorities

are focused on the war against international terrorism and stabilizing

Iraq. Dealing with the federal deficit is a low priority, though

this could become a major drag to the economy in the medium to

long term. However, the Bush administration’s request for

emergency spending of $87 billion to finance operations in Afghanistan

and Iraq and the probability that the budget deficit could be

equal to 4.7% of GDP, are not positive signals on fiscal management.

This puts the upcoming fiscal deficits in the same ball park as

the record fiscal deficits of the early 1980s. Fiscal prudence

is being sacrificed for political expedience.

The bottom line is we are constructive on both the equity and

corporate bond markets in the short term. For the latter the probable

scenario is one shaped by generally tighter spreads, a modest

new issue pipeline, and generally positive economic headlines.

Although some companies have probably opted not to go to the market

to issue debt due to slightly higher rates, we think that rates

remain historically low and are likely to go up as the year continues.

While the improving economy is likely to pull money out of the

bond market and into equities, there will still be enough money

in bonds to make September a positive month for bond market returns.

As for the stock market, the bulls want to run and they will in

the short term. If the momentum continues through September and

sentiment becomes firmer in the belief of a sustainable recovery,

the bulls could continue to run through the end of 2003 and 2004.

By early 2004, the main concern for economic policymakers will

no longer be deflation, but the possibility of looming inflation.

Indeed, in 2004 the U.S. economy could be heading into a period

of stagflation, in which a rising fiscal deficit and rising prices

are matched by little or no growth in the employment area. Consequently,

we say ”Viva los toros!”; at least for now.

By

Darrel Whitten

Investors

who are doubtful of the budding economic recovery in Japan point

to the fact that the recovery is almost entirely export-driven.

If the U.S. economic recovery sputters, they fear, Japan's recovery

will also be nipped in the bud.

The debate about the sustainability of Japan’s economic

recovery revolves around the fact that the growth in the April-June

quarter was driven by exports (+0.4% Q-Q), that domestic demand

continues to shrink (-0.3% Q-Q), and therefore whether Japan's

economy can continue recovering if the U.S. recovery sputters.

This is to a degree true for the tech space, where Japan's major

electronic majors, with a few exceptions, turned in a very disappointing

April-June quarter. Indeed, Sony's nasty earnings surprise and

the downgrading of Fujitsu's credit to junk status by Standard

& Poor's shows that the recovery of earnings and cash flows

has been much slower than investors had hoped.

But it is a misperception that that the recovery in Japan's

is being driven entirely or even mainly by the U.S. recovery.

Looking at Japan’s cumulative exports for the January-June

period, total exports were up a strong 13.9% YoY, but exports

to the U.S. actually declined by 0.3% YoY, and accounted for

27.1% of the total. Exports to the EU were 15.9% of total exports,

and contributed 3.2 percentage points to the overall 13.9 percentage

point gain. Conversely, exports to Asia accounted for 9.4 percentage

points of the 13.9 percentage point rise, with China alone accounting

for 4.4 percentage points of this growth, in surging 49.4% YoY

and accounting for 11.6% of Japan’s total exports. Moreover,

exports to Asia have accounted for the majority of the growth

in Japan's exports this year and for the past several years,

and they now account for 45.1% of Japan's total exports.

On the other side of the coin, the U.S. reported total import

growth of 9.7% YoY during the first six months of calendar 2003,

with imports from Asia rising 10.4% YoY, and the trade deficit

with Asia rising to $267.7 billion versus $232.7 billion a year

earlier. Imports from China rose by 25.0% YoY, and the U.S.

trade deficit with China rose to $107.9 billion, versus $86.3

billion a year previous. Conversely, imports from Japan fell

by 0.5% YoY, and the trade deficit shrank from $66.2 billion

a year ago to $64.4 billion.

In addition, the claim that exports to Asia are really derived

from U.S. demand is also no longer true. Some 34% of the output

of Japanese companies in China, for example, is sold in China,

while 34% is sold back to Japan. Only 32% is exported to third

countries, ostensibly the U.S. and Europe.

The Japanese media has changed its tone regarding China's position–from

portraying China as "the world's factory" to describing

it more as "the world's market," following China's

entry into the World Trade Organization. This is because that,

while China figures very large indeed in U.S. and Japanese imports,

China’s imports are actually growing faster than exports.

The People’s Daily is reporting that imports are expected

to grow 12% to 15% percent to $330 to $340 billion, while exports

are seen rising between 8% and 13% percent to $350 to $360 billion

in 2003. This compares to growth in imports and exports of 21.2%

and 22.3% percent respectively last year.

Indeed, China’s Commerce Minister has been quoted as saying

that China will import over $1,000 billion worth of goods in

the next three years. This growth of course is attracting throngs

of foreign companies. By 2002, over 420,000 foreign and overseas

funded enterprises were registered in China, and the total volume

of actually used foreign direct investment hit $448 billion.

The top imported items into China include; industrial and power

generating equipment, electrical/television and radio goods,

textiles/fibers and fabrics, iron and steel, plastic articles,

mineral fuels, fertilizers, cereals, optical/clocks and precision

goods, and organic chemicals. By far the two largest import

commodities for the first half of calendar 2003 are mechanical

& electrical equipment and high-tech products, where imports

are growing at around 50%. Imports of crude oil, rolled steel

and TV components, while smaller, are also soaring between 80%

and 100% YoY.

The Japanese media's shift from describing China as the world's

factory to describing it as the world's market reflects the

shift in perception by Japanese companies, particularly after

China's entry into the WTO. The media is getting their cue from

Japanese firms, who are shifting the focus of their business

with China from utilizing it as a production base for exports

to selling their products locally.

As of 2002, some 60 Japanese companies had local production

in Asia, of which 20 were in China/Hong Kong. As of the first

quarter of 2003, China sales of the local operations of Japanese

companies accounted for 8% of total overseas sales; 34% of which

was sold in China, 34% of which was exported to Japan, and 32%

of which was exported to third countries, according to METI

data. Sales within the China market were up 12.4% YoY during

the quarter, while exports back to Japan were up 10.9%. Exports

to other countries were up 19.6%.

This "China Card" appears to be having an impact on

Japanese stock prices, if not as noticeably on Japan's GDP growth.

For example, the second up-leg of the current rally in Japanese

stocks is noticeable for its lack of "New Japan" companies,

ostensibly because the weak April-June quarterly numbers have

made investors leery of the traditional tech stocks.

Instead, there has been a focus on cheap "domestic-oriented"

companies. But a look at the top gainers of these "domestic-oriented"

companies indicates that the real play in these stocks is not

their domestic orientation, but China-related demand–particularly

in mature industries where the China business is: a) a life-saver

for the company/industry, and/or b) the Japanese company has

a competitive edge vis-à-vis their global competition

that is also flocking into China.

Snow in Beijing and What it Means for Gold

U.S. Treasury Secretary John Snow visited Beijing recently to

raise the Renminbi (RMB) re-valuation issue with China’s

senior leadership. While the media focus was on currency values

and unfair trade advantages, what is sometimes overlooked is

the potential implications it has for gold.

Firstly, let’s us consider the background behind the pressure

for RMB revaluation, and why for the foreseeable future, both

U.S. and China's interest are interlinked. At the root of the

international unhappiness with China’s currency level is

the country’s rapidly growing trade surplus created by

its “rented economy”. The term “rented economy”

applies since foreign investment controls much of China’s

low cost production. China is becoming the “workshop/factory”

of the world and is holding down global inflation.

China’s senior leadership might still call themselves “Communists”,

however, in reality the country is run the like a holding company

along strict reporting lines with one clear objective, namely

7 to 8 % annual growth. The currency peg between the RMB and

the U.S. dollar is facilitating this growth objective while

at the same time it results in lower interest rates in the United

States. This is because, in order to keep the RMB at the 8.3

% level, China needs to buy up surplus dollars and re-invest

them abroad, foremost in U.S. Treasury bonds. The peg is mutually

beneficial to both China’s growth target and Alan Greenspan’s

need to keep long-term interest rates and inflation low.

As of last month China’s holdings of U.S. Treasury bonds

rose to a record $122.5 billion, less then Japan’s but

far more than any other country. Together Japan and China hold

41.9% of the $1347.2 billion debt the U.S. government owes the

world.

Even though hot money is not allowed in, an unprecedented amount

of foreign currency is flowing into China, to buy land, construction

material and to pay workers to build new factories. These factories

start producing, much of their production is exported and sold

for U.S. dollars, while the raw materials used and the workers’

wages are priced in RMB. As more foreign exchange flows into

the current account, the People’s Bank of China (PBC),

buys up these dollars because the government is committed to

keeping the exchange rate stable.

If it were to stop buying the dollars, the value of the RMB

would quickly appreciate. But the PBC has a problem. If it simply

uses new RMB – creating a liability on its balance sheet

against the dollar assets – the extra money in circulation

within China would soon cause inflation, as indeed happened

in the mid 1990s. That would damage the economy and eventually

hurt China’s export industries, since the prices of Chinese

goods would rise.

So instead of causing inflation inside the country, China is

exporting deflation.

This in turn allowed the Fed to spark an economic revival by

lowering interest rates to 45 year lows without risking inflation.

One weak spot of the recovery, however is the stubbornly high

U.S. unemployment rate. And this is where Mr. Snow comes in.

President Bush has already seen 2.7 million factory jobs disappear

on his watch and he needs to be seen to be doing something about

it in order to be re-elected. Viewed from this perspective,

Mr. Snow’s visit to Beijing is more about U.S. domestic

political issues rather than seriously forcing China to un-peg

the currency.

All of the above leads us to the question what full RMB convertibility

eventually means for gold prices.

China can press onward toward convertibility on the capital

account, which would allow Chinese people more freedom to move

their savings abroad, counterbalancing the inflow of U.S. dollars.

In many ways that is the best option and it is already being

implemented, but it would threaten the steady increase of savings

put in low interest accounts at the state banks. This is the

one thing that keeps China’s financial system stable at

the moment. Historically, the less trust there is in the financial

system the more demand there is for gold.

In addition, strong capital inflows and rising Forex reserves

are already sharply boosting official demand for gold in China.

This is because if the PBC is to retain its proportion of gold

holdings at the current 2.4% of total reserves (European Central

Bank standard: 15%), it would need to increase its gold holdings

by an estimated 120 tons or 60% of gold consumption in China

in 2002.

China already enjoys with 40% one of the highest savings rates

in the world. The closer we get to revaluation, the more USD

dollar savings will be converted into gold.

In order to pave the way, the PBC last year relinquished its

monopoly on imports and exports of gold, the Shanghai Gold Exchange

was established and many Chinese commercial banks are planning

to launch personal gold investment businesses.

The

way forward for China’s central bank and savers in the

coming years is, surely, to diversify out of their huge dollar

holdings and move to back its currency by gold as it heads slowly

but surely towards convertibility on the capital account.

After the Beijing Olympics when the snow falls in the winter

of 2008, Gold might truly glitter.

Michael

R. Preiss serves as Chief Investment Strategist at CFC Securities.

“Zaibatsu” and “Keiretsu” - Understanding

Japanese Enterprise Groups

By

Andrew H. Thorson

Anybody

who is familiar with Japan will recognize the words zaibatsu

and keiretsu. Few, however, know of their meaning and historical

significance. This is the first of several articles that will

explain the origin, historical significance and the current

circumstances of Japan’s enterprise groups, all of which

we loosely tend to refer to as zaibatsu and keiretsu.

This initial article explains the origins of the zaibatsu.

Zaibatsu Formation in the Meiji Era (1868 – 1912)

Zaibatsu generally refers to the large pre-WWII clusterings

of Japanese enterprises, which controlled diverse business sectors

in the Japanese economy. They were typically controlled by a

singular holding company structure and owned by families and/or

clans of wealthy Japanese. The zaibatsu exercised control via

parent companies, which directed subsidiaries that enjoyed oligopolistic

positions in the pre-WWII Japanese market. These economic groupings

crystallized in the last quarter of the 19th century during

the Meiji Reformation.

Zaibatsu first became a popular term among management and economics

experts when the term appeared in the book History of Financial

Power in Japan (Nihon Kinken Shi) as published late in the Meiji

Era. Even in Japan, the term was not commonly used until the

mass media adopted it in the late 1920’s.

The zaibatsu were formed from the Meiji government’s policies

of state entrepreneurialism, which characterized the modernization

of the economy during that era. To understand the significance

of zaibatsu, one must consider at the onset of the Meiji era,

agriculture comprised 70% of Japan’s national production,

and approximately three quarters of Japan worked in farming

related jobs. The government used land tax revenues to fund

the state planning, building and financing of industries determined

by bureaucrats to be necessary for Japan’s economic development.

Meiji bureaucrats did not rely on the free market in reforming

the economy, but they also did not develop the economy alone.

In the 1880’s the Meiji government sold some government-owned

enterprises on special terms to a chosen financial oligarchy

implicitly entrusted with the public interest in developing

the national economy. These enterprises were entrusted to the

influential concerns known as the Mitsui, Mitsubishi, Sumitomo,

Yasuda, Okura and Asano groups.

These private parties and enterprises crystallized over time

into large, integrated complexes steered by the government bureaucrats

into areas of development desired for the reformation of Japan.

To secure compliance, the government provided inducements such

as exclusive licenses, capital funding, and other privileges.

Although Japan badly needed foreign technology, know-how and

capital, the government adopted a policy of shutting out foreign

entrepreneurs with few exceptions in favor of domestic development.

After WWI, when Japan’s economy made huge strides in economic

reformation, the zaibatsu interests began to enter the political

arena to support their interests. Their activities became entwined

with the government in wartime Japan. Eventually, the Potsdam

Declaration that was signed in 1945 required the liquidation

of the zaibatsu as one step to democratize Japan’s post-war

economy.

Zaibatsu Control Structures

Unlike the current situation in Japan, it is said that the zaibatsu

stockholders were relatively strong. While zaibatsu holding

companies directed the enterprise complexes in a pyramid fashion,

stockholding relations cemented together the companies within

zaibatsu complexes. Characteristics of the complexes included

holdings by members of more than half of the holding company’s

stock, and the position of the holding company as the overwhelmingly

largest shareholder of companies within the complex. The stock

of members was rarely sold by other members to third parties.

Under this structure, zaibatsu and their leading holding companies

drove the finance, heavy industry and shipping sectors that

forged the heart of Japan’s economy.

By the 1920’s zaibatsu economic power engulfed the sectors

of finance, trading and many major large-scale industries. From

1914 to 1929, three zaibatsu (Mitsui, Mitsubishi and Sumitomo)

controlled 28% of the total assets of the top 100 Japanese companies.

Even as of 1945, the same complexes possessed 22.9% of the total

assets of all Japanese stock companies.

As will be explained in Part II of this series, subsequent to

the liquidation of the zaibatsu pursuant to the Potsdam Declaration,

new enterprise complexes and groups that resembled the zaibatsu

were resurrected in Japan. There are, however, significant differences

that distinguish the zaibatsu from the modern keiretsu. These

differences and the subsequent formation of the keiretsu will

be discussed in later articles.

Andrew H. Thorsen serves as a Partner in the Tokyo Office

of Dorsey & Whitney LLP, a U.S. law firm. The views of the

author are not necessarily the views of the firm of Dorsey &

Whitney LLP, and the author is solely and individually responsible

for the content above.

THE TIES THAT BIND

The (limited) significance of Thailand’s withdrawal from

the IMF

By

Jonathan Hopfner

Thais are often quick to remind visitors to their country

theirs is the only nation in Southeast Asia that escaped being

colonized by a Western power. It thus comes as little surprise

the early repayment of the $12 billion loan the country secured

from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1997 to cope

with the devastation wrought by the Asian financial crisis

was unveiled with such fanfare. This is because in the eyes

of many Thais the terms and conditions that the IMF attached

to the disbursement of the funds constituted a grave threat

to Thailand’s cherished sovereignty.

Against a backdrop of a massive national flag and patriotic

theme songs, Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra announced that

Thailand had repaid the loan in full on July 31, one year

ahead of schedule. He swore to his rapt audience that this

was the “last time the country would be indebted to the

IMF” and remarked that the debt had been a “pain

to the nation.” Soon after, the IMF announced it would

close its Bangkok office in mid-September. While it insists

its officials will continue to visit Thailand regularly to

discuss policy with local officials, there is little doubt

the lender’s influence here is on the wane.

Some of Thailand’s more opportunistic lawmakers have

seized on the country’s recent freedom from the IMF’s

shackles. Calls have increased for the repeal of 11 laws,

including those governing bankruptcy and property ownership,

that were introduced by the previous government partially

to conform with the IMF’s loan conditions and are widely

alleged to favor foreign over local investors.

So is this, as some observers have surmised, the end of an

era? Was the Prime Minister’s characteristically nationalistic

bombast yet another indication of Thailand’s growing

determination to assert its full economic, as well as political,

independence? Will Western policymakers and investors find

their views are no longer taken into account by a government

determined to pursue its own goals?

The short answer is no, not really, because Thailand took

little of the IMF’s advice to heart to begin with. In

a 1998 letter of intent outlining the steps the government

should take in the following year the IMF called on Thailand

to draft plans for the full privatization of the state energy,

tobacco, transport and utility monopolies, as well as the

freeing up of the telecom market. Five years later, the government

has taken some very tentative steps towards these goals –

a stake in Thai Airways has been floated on the Stock Exchange

of Thailand, and the Petroleum Authority of Thailand and Telephone

Organization of Thailand are now, in name at least, private

entities – but for the most part the privatization and

liberalization of these crucial sectors remain as elusive

as they were five years ago.

Even the changes instituted under the IMF’s auspices

– the tightening up of Thailand’s bankruptcy legislation,

for example – have hardly proven as sweeping as expected.

While the new laws may have been designed to boost the rights

of creditors, they seem to be less than adept at fulfilling

this task in practice. Witness the ongoing saga of debt-ridden

Thai Petrochemical Industry (TPI). Throughout a seemingly

endless proliferation of suits and counter-suits, the Thai

courts have allowed founder Prachai Leophairatana to maintain

nominal control of the company despite the objections of creditors

such as Bangkok Bank and Germany’s KfW, who apparently

have the right to appoint the administrators of an insolvent

firm under Thailand’s bankruptcy laws.

The reality is the economy at its strongest point since the

1997 crisis – growth surged to 6.7 percent in the first

quarter of this year, and Thailand’s bourse has recently

ascended to its greatest heights since 1999. Any changes to

Thailand’s investment and ownership policies are likely

to be a result of the government’s perception that it

is, for the first time in years, in a position of strength,

as opposed to a desire to test the country’s newfound

“freedom” from its IMF obligations.

There is every possibility, then, that the government may

indeed introduce legislative changes that appear less than

friendly to foreign investors – but only to a point.

IMF or no IMF, Thailand’s commitments as a member of

the World Trade Organization (WTO) and Association of Southeast

Asian Nations (ASEAN) will keep the country squarely on the

path of reform and openness – the telecom sector, for

example, must be completely liberalized by 2006 if Thailand

is to conform to its WTO obligations.

Healthy competition within Asia for foreign capital is also

likely to prevent the Thai government from implementing any

laws that would severely limit the rights of multinationals

doing business there. With concerns rising about an outflow

of foreign business operations to China and other countries

in the region taking steps to deal with this threat –

Singapore recently amended its pension system to reduce its

notoriously high labor costs – Thailand will have little

choice but follow suit.

Many historians argue that the country’s then-rulers

saved Thailand from being colonized by exhibiting a healthy

amount of pragmatism. They simultaneously made necessary concessions

to foreign powers while fostering a sense of unity among their

own population. Despite the passing of the IMF and its increasingly

nationalist rhetoric, the current government will likely do

the same.

Indonesia and Islamic Terrorism – More Than a Thorny

Problem

By

Scott B. MacDonald

In early August, the JW Marriott Hotel in Jakarta was bombed.

The bomber was an Islamic radical, who drove a van into

the front of the hotel, killing 12 people and wounding over

a hundred others. Most of those killed or injured were Indonesian.

The Marriott bombing follows the Bali bombing of October

2002, two other bombings in Jakarta (one at the parliament)

and an alleged plot to kill the country’s president

Megawati Sukarnoputri. Although Indonesian authorities are

reluctant to admit it, the rise of Islamic terrorism runs

the risk of polarizing society and endangering the relatively

secular nature of the government. It also casts a large

shadow over the future of the country’s fledgling democracy

as well as the attractiveness of Indonesia as a place for

foreign investment. While the Indonesian government is a

considerable distance from being ousted from power, local

radical Islam and its foreign links to al-Qaeda and Jemaah

Islamiah (JI) represent a very challenging problem with

long-term implications for Southeast Asia’s largest

country as well as the rest of Asia.

There are two sides of the coin in looking at Indonesia

and Islamic terrorism. On one side of the coin, Indonesia

has a long tradition of a tolerant form of Islam, which

has functioned as a support for political stability. It

has also been a pillar of Indonesian nationalism, a force

that helps bind the country together. This was especially

the case during the struggle for independence during the

1940s. During the Suharto years, Islam was carefully controlled

and there was an emphasis placed maintaining a secular society,

able to accommodate a Muslim majority, but carving out a

tolerance for the Hindu, Christian and other smaller religious

communities. With the end of the Suharto years and the advent

of Indonesian democracy, the role of Islam in society suddenly

became more central. Indeed, with the departure of East

Timor, the overall numbers of Muslims as a percentage of

the total population increased.

The other side of the coin is that as the Islamic face of

Indonesian society has become more distinct and more mainstream,

the door has also opened for radicals within the same community

to emerge from the shadows, developing international ties

to like-minded groups and recruiting more followers. Certainly

the shift to a more open political system has brought about

a higher degree of uncertainty in Indonesia. Together with

the round-robin of presidential leadership since 1997 and

tough economic times until recently, radical Islam has become

attractive as it projects a clear-cut, simple answer to

complicated issues.

Another aspect of the rise of radical Islam in Indonesia

is that the political class is seeking to manipulate this

force. With the unpopularity of the American war against

Iraq and the close U.S. alignment with Israel vis-à-vis

the Palestinians, another Islamic people, radical Islamists

have been quick to articulate their views and to find a

sympathetic audience in the majority of Indonesians. This

by no means infers that most Indonesians favor radical Islam,

the creation of a theocratic state along the lines of Iran,

or are inclined to attack the West and its allies. What

it does mean is that radical Islam touches a sensitive spot

in the country’s identity – the West has long

looked down on Islamic peoples. In a sense, there is a sense

of grievance. After all, the Dutch long colonized Indonesia

and took its natural resources. Western companies made money

in the country, and Suharto was long supported by the United

States. In addition, it is argued the IMF made life miserable

for many Indonesians with its poorly conceived economic

policies.

The danger is that elements of the political elite are still

playing to radical Islamic groups, or at the very least

pandering to public sentiment vis-à-vis the unfairness

of an international order dominated by the United States.

The comments of Vice President Hamzah Haz in calling the

United States, the “king of terrorists for its war

crimes in Iraq” certainly must be seen in this context.

Haz was responding to international criticism that Indonesia

had been lenient in sentencing Abu Bakar Bashir, the spiritual

leader of JI, to only four years of jail. Haz is the leader

of the conservative Islamic United Development party (PPP).

He has in the past been willing to be seen courting some

of the country’s more radical Islamic figures.

While some groups are playing to the Islamic radicals, others

remain strongly opposed or are waiting for their turn to

take advantage of potential weakness in central authority.

President Megawait Sukarnoputri is conducting a war against

Islamic separatists in Aceh (on the northern tip of Sumatra)

and is seeking to contain separatists in other regions.

At the same time, presidential elections loom in early 2004.

If the President slips in conducting the war, if she pushes

too hard on Islamic groups in a predominantly Islamic country,

or if she appears to be in the lap of the United States,

her political prospects are likely to weaken. Moreover,

she must tread softly with the military. Any loss of power

from the civilian part of the political spectrum could be

gained by the military, one of the few cohesive institutions

in the country. In the past, it has also been one of the

most influential. If civilian leadership is inadequate,

there are leaders within the armed forces that might be

tempted to step into the picture, probably in the shadows,

much like Indonesian puppet plays.

What complicates matters for Indonesia is that it is not

a small, insignificant country. Rather, it is a pivotal

nation, located astride major lines of communication and

trade between East Asia and the Middle East and Europe.

It is also the world’s largest Islamic nation and a

major producer of oil and natural gas. For all these reasons,

what happens in Indonesia matters. Consequently, the approach

of the Megawati government to radical Islamic terrorism

is a concern to more than just the local population. It

is a point of concern to Washington, Tokyo, Beijing, Manila,

Singapore and Manila. The failure to implement Financial

Action Task Force (FATF) money-laundering regulations, which

are aimed at hurting illegal financial activities in the

country -- which could aid Islamic terrorist groups -- gives

the impression that Indonesia is soft on tackling the problem.

Perceptions remain important in a globalized world –

like it or not. This is important for attracting foreign

investment as well as how the country interacts with the

rest of the region. While the U.S. has often pushed too

hard on Indonesia and certainly played to the sense of Islamic

grievance, Indonesia’s political elite also has to

consider its responsibility to its citizens in providing

sustainable economic development, a better standard of living,

and clear government. Supporting men with bombs willing

to kill their fellow Indonesians in grisly acts of violence

is not going to build a better future for the country.

|

|

See

your article or advertisement in the KWR International Advisor.

Currently circulated to 10,000+ senior executives, investors,

analysts, journalists, government officials and other targeted

individuals, our most recent edition was accessed by readers

in over 60 countries all over the world. For more information,

contact: KWR.Advisor@kwrintl.com

|

|

By

Andrew Novo

Following the lead of the United States, the Italian economy

dipped into recession in the beginning of August after

posting negative growth for the second quarter of 2003.

More recently, France and Germany have joined the ever-growing

list of nations suffering economic contraction. In Italy,

as in many other countries, the recession was an expected

phenomenon based on consequences from the war in Iraq

and “a poor international climate.” Shrinking

exports due to a strong euro and decreased tourism have

not helped matters and the outlook among most economists

in Italy, and throughout the world, is for little or no

growth for the rest of the year. Once again, the Berlusconi

government is forced to deal with an economically challenging

situation at a time of increasing political volatility.

Over the past summer, Berlusconi’s coalition, Casa

delle Liberta, suffered a defeat in local elections in

Friuli-Venezia Giulia (a region in the northeast) to the

opposing left-wing L’Ulivo coalition. More significantly

for Berlusconi’s government, the incumbent candidate

for the regional council, from the Prime Minister’s

own Forza Italia party, did not run. Instead, the Lega

Nord, the right-wing coalition partner of Forza Italia,

insisted that its own candidate, Alessandra Guerra, stand

for election. Guerra was defeated. Violent recriminations

within the Casa delle Liberta resulted in threats from

the leader of the Lega Nord, Umberto Bossi, to pull out

of the Prime Minister’s coalition. At the end of

August, Berlusconi and Bossi have been at odds again,

this time over the issue of reforming Italy’s pension

system.

Italy’s weakened economic position has further complicated

matters between the Prime Minister and his separatist

northern ally. With Italy’s monetary policy governed

by the European central bank, the Berlusconi government

is left to make due with fiscal policy in order to bring

about a return of economic growth. During his 2001 campaign,

Berlusconi promised tax cuts and decreased government

spending, the latter objective to be achieved primarily

through a streamlining of the turgid and wasteful Italian

bureaucracy. The federal tax cuts put forward in the 2003

and 2004 budgets came about through the creative bookkeeping

of Finance Minister Giuliano Tremonti in the face of skepticism

and concern from the European Union which is wary of Italy’s

burgeoning deficit. The federal tax cuts (in excess of

five billion dollars) will be countered by decreased government

transfers to local governments. This will result in increased

local taxes. The net gain for Italian citizens will be

minimal.

In keeping with his platform of reform and decreased government

spending, Berlusconi has most recently set his sights

on reducing the bloated Italian pension system. The Prime

Minister hopes to tighten the budget by decreasing government

spending in this area. However, this measure has stoked

the smoldering embers of contention with the Lega Nord.

Berlusconi’s announcement of his desire to raise

the retirement age from fifty-seven to sixty years of

age by 2010 has met with staunch opposition from the Lega

Nord. The Lega draws considerable support from voters

who retire on pensions at fifty-seven after thirty five

years of work. Eighty percent of such government pensions

are received by people in the north. The issue draws important

battle lines. If Berlusconi chooses to proceed with his

pension plan it could well cost him the support of the

Lega, which has already withdrawn from cabinet activities

in the wake of the June election defeat. It should be

remembered that differences over pension reform caused

the withdrawal of the Lega Nord from Berlusconi’s

first government in 1994 resulting in its collapse. It

seems that history is repeating itself – a dangerous

proposition for the Berlusconi government. If the withdrawal

of the Lega induces an exodus of the extreme right from

the Casa delle Liberta, the Prime Minister will no longer

hold a majority in the Italian parliament.

Further complicating the situation of ifs and ands is

the present recovery of the American economy. Just as

Italy followed America into recession, it will likely

drag itself out on the coat tails of the United States.

If this happens swiftly enough, the pressure to cut government

spending by reforming the pension system will surely dissipate,

the voices denouncing Mr. Berlusconi will soften and the

Prime Minister will ride the recovery into the re-election

campaign.

|

|

FacilityCity

is the e-solution for busy corporate executives. Unlike

standard one-topic Web sites,

FacilityCity ties real estate, site selection, facility

management and finance related issues into one powerful,

searchable, platform and offers networking opportunities

and advice from leading industry experts.

|

Israel

and Globalization Israel

and Globalization

By

Jonathan Lemco

Israel is one of the few, if not the only, democracy in

the Middle East. It also has the most dynamic economy

and most vibrant entrepreneurial culture. Its economic

policy-makers are proactive and its workforce is one of

the most technologically innovative in the world. This

is best evidenced by its success in devising new materials

and techniques applicable to the defense, electronic and

other industries. Not surprisingly, Israel has benefited

enormously from globalized trade and investment. This

is despite Israel’s relatively small population base

and its precarious strategic position. Of course, as the

largest recipient of financial aid from the United States,

Israel enjoys a particular advantage.

Since its inception in 1948, the Israeli economy has been

fairly open to international markets. In the 1990s for

example, the information technology and communications

sector in Israel grew five-fold, reaching 14% of GDP.

On the other hand, technologies are spread around the

world through multinational companies, an area in which

Israel is weak. The number of Israeli multinationals in

the high-tech sector, as expressed in company size, is

low. By definition, most Israeli high-tech companies are

small firms. And they are vulnerable to a highly volatile

global high technology sector.

Broad Macroeconomic Issues

To compete in a globalized world, Israeli policy-makers

must seek price stability as a primary monetary policy

goal, with a second goal of tempering business cycles.

The main policy tool is short-term interest rates. In

Israel there were two clear deviations from stable interest

rate parameters; in 1998 and again in 2001. Both times,

lowering the high interest rate created turmoil. Interest

rate policy in a globalized world economy must be stable

while adhering to medium- and long-term inflation targets.

With regard to budgetary policy, the Ministry of Finance

must continue its policies of fiscal prudence. At present,

Israel has a moderate external debt burden due to capable

Central Bank management and strong capital inflows since

the mid-1990s. Israel’s ample reserves of $24 billion

cover its external financing gap. Direct international

investment in Israel is up in 2003 as well. But Israel

does have high government deficits of 5% of GDP and public

debt burdens. Unemployment is too high at 10.8% as of

April 2003. Many of Israel’s domestic costs are due

to external shocks associated with its complex security

situation. Future budgets should be rigid when it comes

to government expenditures, and flexible regarding the

impact on the business cycle through infrastructure investments.

Otherwise, the risk of recession increases.

Israel is a trading nation, and this has contributed to

lower prices and a higher standard of living. As a small

nation, pursuing international trade agreements are the

only way it can ensure its relatively high levels of prosperity

can be sustained. Indeed, Israel’s export oriented

economy has generated per capital income that is similar

to some EU countries. It is a virtual par with Spain and

higher than Greece and Portugal. The Israeli per capita

income is much higher than the 10 countries that will

join the EU in 2004. However, most of these countries

are growing economically while Israel is in the third

year of a recession.

That said, if there is progress attained by the internationally

sponsored ‘Road Map” aimed at resolving the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict, coupled with a global economic

recovery, then the Israeli economy should emerge from

recession in 2003. At 0.5% in real terms this year however,

growth remains below potential.

Globalization’s Reach into Israel

As of August 2003, 2.2 million Israelis (32.8% of the

total population), use the Internet. This is one of the

most wired nations in the Middle East. Further, the telecommunications

market in Israel is growing rapidly. Data communications

is the growth engine, and the forecast for Israeli data

communications growth is 31.2% through 2007. Wireless

data communications revenue accounts for half of the data

communications total and should expand by an average of

43% per year until 2007, according to the Israel High-Tech

and Investment Report.

Also, according to the Israel High-Tech and Investment

Report, the Israeli telecommunications market revenue

amounted to $3.78 billion in 2002, of which $2.6 billion

came from cellular communications and $1.17 billion from

fixed line communications. Clearly, this is a burgeoning

industry poised to benefit from greater international

ties.

Israel’s biotech sector is also a growing force to

be reckoned with. BioTechnology General, InterPharm Laboratories,

and especially Teva Pharmaceuticals are the largest of

the approximately 140 firms developing world class pharmaceutical

and other products and technologies. The biotech industry

in Israel employs about 40,00 people and its output, as

of June 2003, was in excess of $800 million per year.

Teva Pharmaceuticals alone was responsible in 2002 for

more than $550 million in exports of its Multiple Sclerosis

Copaxone drug.

The number of biotech startups is high and equals the

number of companies in such countries as Switzerland,

Sweden and France. Furthermore, Israel’s medical

device industry, numbering more than 400 companies, is

growing as well and is a world leader in the production

of cardiac stents.

Finally, Israeli defense exports hit an all-time record

in 2002. Signed contracts for defense industry deals with

foreign armies reached $4.18 billion, a nearly 70 percent

rise compared to 2001. The main customers for Israeli

weapons systems are the U.S., followed by India and various

Southeast Asian countries. Not surprisingly, the identity

of many of the countries acquiring weapons systems are

not revealed. As of July 2003, Israel is fifth as a military

exporter behind the U.S., EU, Russia and Japan. But it

is also among the leaders in exporting electronic equipment

and high-tech military equipment.

Conclusion

Israel is a small country faced with a challenging strategic

environment. But its population is educated and its industries

have produced goods and services that are in demand worldwide.

The Israeli economy has demonstrated an ability to compete

with much larger competitors. In short, globalization

has offered opportunities to Israel that have allowed

it to transcend its small size and realize a standard

of living for its citizens that are among the highest

in the middle east.

eMergingPortfolio.com

Fund Research tracks country/regional weightings and fund flow

data on the widest universe of funds available to emerging market

participants, including more than 1,500 emerging market and international

equity and bond funds with $600 billion in capital and registered

in all the world's major domiciles. http://www.emergingportfolio.com/fundproducts.cfm.

eMergingPortfolio.com also offers customized financial analysis,

data and content management services on emerging and international

markets for corporate and financial Internet sites. For more information,

contact: Dwight Ingalsbe, Tel: 617-864-4999, x. 26,

Email: ingalsbe@gipinc.com.

BUSINESS

Russian Tycoons Face the Heat

By

Sergei Blagov

MOSCOW - The ongoing controversy around Russia's top oil

company, Yukos, has prompted fears that the Kremlin might

review the privatizations of the 1990s. Meanwhile, Russian

official statements remain somewhat ambiguous. Notably,

President Vladimir Putin has called for a crackdown on

economic crimes but said individual rights should be respected,

carefully avoiding taking sides in a dispute around Yukos.

Putin's previous comments were marked by his characteristic

ambiguity and avoided any direct reference to Yukos. However,

Putin spoke out against the use of detention for suspects

accused of economic crimes.

The probe into Yukos began with the arrest in July of

Platon Lebedev, a right-hand man of Russia's richest man,

Yukos chief executive Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Lebedev is

the billionaire chairman of the board of Group Menatep,

the holding company that owns 61 percent of Yukos.

Prosecutors have charged Lebedev with defrauding the state

of $283 million in the 1994 privatization of the Apatit

fertilizer company. His arrest was followed by criminal

investigations into its alleged tax evasion and role in

several murders of officials and businessmen.

Khodorkovsky, who has backed some political parties that

compete with the main pro-Kremlin party in December's

parliamentary elections, has dismissed the accusations

against his company and blamed a power struggle within

President Putin's administration.

In 1995, Khodorkovsky bought Yukos, the second biggest

oil company in Russia, and the fourth largest in the world,

thus becoming a billionaire almost overnight. In oil reserves

(11.4 billion barrels) Yukos is close to British Petroleum

(about 12 billion barrels), which is worth some $180 billion.

Khodorkovsky bought 78 percent of Yukos shares for $170

million and even this money was believed to be budget

funds operated by Menatep Bank. Menatep Bank, which belonged

to Khodorkovsky, had been entrusted with holding the auction

to sell Yukos. There is therefore no big suprise that

Khodorkovsky proved to be the winner.

Because the privatization laws that were in place in the

1990s left much to be desired, companies that were won

in rigged auctions, like Yukos, are now open to attack.

Recent public opinion polls, conducted in the wake of

the first moves against Yukos, show that the vast majority

of Russians are still bitter about that. One poll found

that 77 percent think that privatization should be reviewed.

Arguably, there are people in the Kremlin who agree.

Meanwhile, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov has

publicly spoken out against jailing those found guilty

of economic crimes. Kasyanov's open siding with Yukos

is a sign that the struggle between Yukos and the prosecutors

is only part of a bigger battle for economic leverage

and power between the old elite that obtained power and

vast wealth under President Boris Yeltsin and the former

KGB colleagues of President Putin. Kasyanov, who has been

a key government player since the early 1990s, is seen

as a member of the old Yeltsin elite, also known as the

Family.

The dispute around Yukos has been seen as an assault on

Khodorkovsky for supporting opponents of Putin's allies

in this December's parliamentary elections.

Even Guennady Zyuganov, leader of the Russian Communist

Party, has described the assault on Yukos as an action

in "barbarous forms." "As soon as Yukos

leadership indicated their political ambition, a strike

ensued," he told the journalists in Moscow earlier

this month.

Until recently, Zyuganov has repeatedly denounced the

1990s privatizations as a sham. Yet earlier this year

media reports have suggested that Khodorkovsky provided

financial backing for Zyuganov's Communists, but he has

denied this.

There should be no surprise that there have been warnings

against reshaping corporate ownership rights in Russia.

Undoing privatizations of the 1990s would be "suicidal"

for Russia, Economic Development and Trade Minister German

Gref has stated.

Moreover, yet another Russian oligarch, Vladimir Gusinsky,

51, was detained in August at the Athens International

Airport on his arrival from Tel Aviv, where he has been

living in self-imposed exile since fleeing Russia in 2000.

Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has reportedly filed

a request to extradite Gusinsky from Greece. The charges

are linked to the alleged embezzlement of a $250 million

loan extended by state-controlled Gazprom to Gusinsky's

former Media-MOST empire in the 1990s. The team investigating

Gusinsky is headed by Salavat Karimov -- the same person

who is investigating Yukos on suspicion of stealing state

property.

In April 2001, Spain turned down a request from Russia

to extradite Gusinsky, who holds Russian and Israeli passports

and was living there after fleeing Moscow to escape what

he called politically motivated prosecution over his media's

critical reports of the Kremlin. Authorities denied they

were muzzling independent media, saying they instead were

investigating financial wrongdoings at Media-MOST.

The Kremlin crackdown on one of the country's business

moguls is not just another twist in the ongoing political

struggle -- it says a lot about the very nature of the

political system, argues Lilia Shevtsova, a senior associate

of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Putin

nor his praetorians had any intention of starting nationalization

-- the president's hungry wolves were just hoping for

a slice of the pie, she said.

It has been understood that by launching criminal probes

President Vladimir Putin's administration wants to remind

the tycoons that the should stick to business and stay

out of politics.

"Should the state decide to launch a second bolshevik

revolution, the consequences would be severe, yet that

does not mean that nothing can be done to redress the

abuses associated with privatization," said Marshall

Goldman, associate director of the Davis Center for Russian

and Eurasian Studies, Harvard University. "The state

could raise, and make a strenuous effort to collect, taxes

on both production and exports, but such measures would

probably not be enough to satisfy public anger and resentment,"

Goldman said.

The odds then are that there will always be the threat

that not only Putin, but future Russian leaders will also

periodically feel tempted or pressured to harass other

oligarchs, he said.

|

Buyside

Magazine reaches active institutional investors monthly

with news and analysis of the equities markets. Buyside

takes readers beyond news of the current business

climate to report industry and market

|

| trends

that are crucial for investors to understand -- not

simply the latest business trends or product releases.

Buyside and BuysideCanada are available in print, and

online at www.buyside.com.

Subscriber information is available on Buyside's home

page. |

KWR Viewpoints

Creating

Value Key to Korea's Long-Term Success Creating

Value Key to Korea's Long-Term Success

This article was originally published in the Korea Times

on August 31, 2003

Despite

its underlying attractiveness and reasonably strong macroeconomic

fundamentals, international investors remain cautious about South

Korea.

While the SK Global situation is largely resolved, and growth

prospects and fiscal flexibility are high by regional standards,

too many uncertainties prevail.

This is true both on the peninsula and in global markets as a

whole.

South Korea suffers from a greater threat from the North, the

effect of a strengthening China, a still weak Japan and an unclear

economic outlook in the United States and Europe.

This is compounded by concerns over consumer debt, labor tensions,

and worries over the sustainability of reform and the ability

of the new government to operate in an effective manner.

Recent announcements that South Korea has entered a recession

for the fourth time in history and that its fiscal surplus has

dramatically declined only leads to further concern.

To reassure investors, many stress South Korea's ability to restore

growth and momentum as a recovery takes shape in the U.S. While

possible, this is dangerous as it presupposes there will be a

U.S. recovery and creates a scenario where Seoul's success is

dependent upon events beyond its control.

It also contributes to a perception of South Korea as a high beta

economy, that is more a leveraged play on growth in the U.S. rather

than a promising story in and of itself.

Therefore, in the present environment, where investors seek to

lower their risk exposure, South Korea suffers in comparison with

other investment destinations, including China, Japan, and even

India, Russia and Thailand, which many believe offer better value

as well as a lower dependence on U.S. markets.

To minimize this reliance on U.S. economic performance, Seoul

needs both to focus on the development of value-oriented strategies

and to explain these developments in an effective manner.

Business theory holds a competitive advantage is defined through

lower cost or greater value, preferably both. Companies such as

Samsung and LG Electronics and Hyundai Motor are learning this

lesson.

They are building market share - irrespective of the underlying

contraction and deflationary pricing trends troubling the global

electronics, technology, auto and other industries.

For example, market research firm Display Research noted Samsung

Electronics took a 30.2 percent market share in North America's

LCD TV market and 34.3 percent of Europe's during the second quarter.

It surpassed Japan's Sharp, estimated to have held 25.9 percent

of the U.S. market and 17.5 percent of Europe's.

Samsung officials also express confidence the firm will soon beat

Sharp in the Japanese LCD TV market.

Similarly, Hyundai Motor is also achieving success, recently announcing

that rising exports had countered an 11 percent contraction in

domestic sales, and its first-half net profit jumped 10.6 percent

year-on-year to an all-time high of 988.5 billion won.

Korean firms are also gaining market share in cellular handsets

at the expense of Nokia, Motorola and other long-established competitors.

In addition to a keen commitment to product development, it is

no coincidence these firms are also among South Korea's savviest

marketers. They devote large amounts of funding to building an

extremely important intangible - brand image.

Their success is reflected in Interbrand and BusinessWeek magazinesrecent

designation that Samsung Electronics possesses the fastest growing

brand value in the world - rising about 30 percent over each of

the past two years.

The long-term success of Korean firms will largely be determined

by their ability to move beyond the tendency to base their competitiveness

almost exclusively on cost-efficiency.

Enhanced brand value not only increases demand and economies of

scale, but also leads to higher margins and profitability. Combined

with additional attention to financial communications, investors

are also more content to maintain a long-term commitment.

Once again, one can observe this phenomenon in the performance

of Samsung Electronics. It reported a 41 percent decline in its

second quarter earnings, yet continues to trade at an all-time

high.

South Korea as a whole must also incorporate these lessons if

it is to successfully reposition itself as the "Dynamic Hub

of Asia" and to realize the vision of becoming an international

service and logistics center.

The nation must do a much better job of defining and telling the

"Korea Story" and the capabilities of individual firms

and its population. This requires ongoing planning and outreach.

It will not be achieved by the occasional ad hoc announcement,

advertisement, road show or short-term domestically-focused efforts

that have been organized in the past when some emerging problem

or issue was deemed worthy of an immediate response.

While many of these efforts have been well organized and well

received by participants, they do little to create sustainable

value.

Rather insufficient follow-up and thought has been allocated to

the ongoing communications and interaction that is part of every

successful public and investor relations initiative.

The fact is while the nation possesses a wealth of characteristics

that makes it, and its individual firms, an attractive investment

story, U.S. investors and opinion leaders - beyond the small,

dedicated group of Korea watchers and members of the Korean-American

community -remain largely unaware of its potential.

Therefore, while South Korea has done far more than most other

Asian nations in implementing reforms and the measures to promote

a more dynamic and competitive business environment, U.S. investors

and businesses continue to view it as a difficult and unapproachable

market that is extremely dependent on growth in the U.S.

Similarly, Korean firms possess real technological and other advantages

in many industries, yet with few exceptions these achievements

go unrecognized and the firms do not benefit from the additional

market share, pricing power and valuation premium that should

result.

Brand value and investment sentiment are not made, nor are major

transactions contemplated, simply on the basis of one-day conferences

or seminars. They require ongoing communications and interaction.

Just as a U.S. company would be unlikely to achieve success in

South Korea through occasional visits to Seoul, it is not possible

to communicate complex messages and to manage relationships in

the U.S. simply on the basis of random, disconnected activities.

In spite of its underlying attractiveness, it is by no means clear

why foreign investors, businesses and consumers should buy into

the Korea story as a whole or, with a few notable exceptions,

as individual firms.

It is therefore the challenge of every Korean company and government

organization to invest in the activities needed to overcome this

important obstacle.

Otherwise, while there will inevitably be cyclical upturns, South

Korea's economic competitiveness will be eroded over the long-term

in favor of lower-cost and more value-oriented competitors.

|

|

See

your article or advertisement in the KWR International Advisor.

Currently circulated to 10,000+ senior executives, investors,

analysts, journalists, government officials and other targeted

individuals, our most recent edition was accessed by readers

in over 60 countries all over the world. For more information,

contact: KWR.Advisor@kwrintl.com

|

Emerging Market Briefs

By

Scott B. MacDonald

Chile

– Unemployment Falls: The Chilean economy has made

a substantial recovery in 2003, though high unemployment has remained

a lagging point of concern. It now appears that the employment

picture is beginning to brighten. The government announced in

late August that the jobless rate fell to 9.1% in the three months

to July, from 9.4% at the end of the similar period in 2002. Pushed

along by additions in manufacturing, building and retailing, employment

grew by 3.3.%. Real GDP in 2002 was 2.1%, reflecting tough global

markets for most goods exported by Chile. For 2003, real GDP is

expected to be 3.5%, well ahead of most of Latin America. Chile

– Unemployment Falls: The Chilean economy has made

a substantial recovery in 2003, though high unemployment has remained

a lagging point of concern. It now appears that the employment

picture is beginning to brighten. The government announced in

late August that the jobless rate fell to 9.1% in the three months

to July, from 9.4% at the end of the similar period in 2002. Pushed

along by additions in manufacturing, building and retailing, employment

grew by 3.3.%. Real GDP in 2002 was 2.1%, reflecting tough global

markets for most goods exported by Chile. For 2003, real GDP is

expected to be 3.5%, well ahead of most of Latin America.

India

– S&P Upgrades the Outlook on Banks: Like many

developing countries, India’s track record in banking has

not been stellar. The practice of stuffing state-owned banks with

bad loans to money-losing state-owned companies was well rooted

in the system. In addition, competition was long kept under control.

Although there are still issues of inefficiency, bad loans and

the need to upgrade technology in many banks, there have been

positive changes in recent years. Standard & Poor’s in

early September 2003 changed the outlook of the banking system

from negative to stable. In doing so, the rating agency commented:

“Key watershed structural reforms in India so far have improved

the health of the banking sector’s asset quality, profitability,

and capital adequacy.”

Malaysia – Growth on the Upside: Malaysia’s

real GDP for Q2 2003 expanded at a faster rate than expected,

hitting stride at 4.4%. The median forecast by economists had

expected 3.9%. Economic growth was fuelled by rising demand for

commodities and higher prices, which boosted exports. This more

than compensated for a decline in electronics exports and the

impact of SARS. A government stimulus package, launched in May,

also helped stimulate growth.

Pakistan

– Earning Praise: The management of the Pakistani

economy has never been easy. Beyond facing ongoing problems that

almost always threaten political stability, the economy has struggled

to find a competitive nitch in the global economy and attract

foreign investment. Consequently, when there is good news it should

be acknowledged. In late August, the Asian Development Bank (ADB)

commended Pakistan for its economic recovery. The ADB’s annual

economic update for the South Asian country forecast economic

growth in the year to next June (Pakistan’s fiscal year)

would rise to 5.3%. In the fiscal year that just ended in June

(2002-2003), real GDP was a robust 5.1%, up from a more modest

3.1% in 2001-2002. Helping stimulate economic expansion over the

last few months has been the early monsoon rains, which significantly

ended a brutal three-year drought. The expectation is that with

a more regular pattern of weather, the agricultural sector will

have a much stronger performance. This is important as agriculture

accounts for a quarter of GDP and more than two-thirds of the

nation’s 145 million people rely directly or indirectly on

farm incomes.

The ADB also noted that a sharp fall in interest rates has reduced

borrowing costs for the corporate sector and the better business

environment has helped fuel a recovery in the Karachi Stock Exchange,

up more than 60% in 2003. Remittances from overseas Pakistanis,

worth around $4 billion last year, are helping to fuel growth.

Although Pakistan faces tough political issues, there has been

a greater degree political stability under the current Musharraf

government over the last couple of years. This does not ignore

the challenges of radical Islamic groups that have conducted their

own war against the West in a series of bombings. However, the

political issue is a point of concern to the ADB going forward.

The ADB warned that if relations between the government and opposition

remain tense over the position of General Pervez Musharraf, the

country’s leader, some of the economic gains could be jeopardized.

Pakistan remains one of the more geo-politically significant countries

in Eurasia, with its borders touching Afghanistan, Iran and India

and being close to the Persian Gulf. Progressive economic development

is critical if this pivotal state is to remain anchored as an

ally of the West. Clearly grinding poverty and inequality are

the breeding conditions for radicalism, be it Islamic or another